From the November 2023 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

I had opinions about the Philip Guston show long before it came to Tate Modern. Solicited opinions, broadcast opinions, opinions in print. I had opinions in October of 2020, after its British co-curator Mark Godfrey was suspended by the Tate for criticising the show’s postponement. Programmers feared the incendiary potential of displaying Guston’s Klansman paintings in the era of Black Lives Matter (and no doubt the poor optics of a banner show by yet another dead white man). I had opinions in May 2022, when the exhibition finally began its tour at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston complete with an ‘Emotional Preparedness’ statement offered to visitors.

The show became a lightning rod for discussions around the capacity of art to offend and upset, about an artist’s role in a time of violent unrest and about the clunky response of art institutions to Black Lives Matter. The discourse enrobed Guston in moral purity – a white man who understood racism as systemic and scrutinised himself in that context – as if to justify the show’s importance. Things reached such heights of hagiography that Guston felt almost untouchable. When a US critic pointed out the use of racial caricatures in Guston’s satirical drawings of Richard Nixon – Poor Richard (1971) – it felt shocking above all because she had broken ranks.

I became steeped in the meta-narrative of this exhibition. I hefted Robert Storr’s bicep-taxing paving slab of a monograph. I read Musa Mayer’s tender piecing together of her father’s life, Night Studio (1988), and became inappropriately transported by Edward Weston’s brooding portrait of Guston on its cover.

But while I may have thought a lot about Guston (interpret that as you will), in truth I had seen very little of his work. The Poor Richard series. Other 1970s works on paper. Perhaps half a dozen major paintings. That’s it.

As the exhibition at Tate approached, I worried about all the para-Gustonian baggage that would follow me into the gallery, clanking in the background like tin cans on a wedding car. How to look at this art of contextual clamour without being distracted by the contextual clamour of the show itself?

Couple in Bed (1977), Phillip Guston. Art Institute of Chicago

I arrived over-sensitised and flinched at early curatorial texts leaning hard into Guston’s mural made in 1932 in response to (and subsequently damaged by) the violent activities of the Ku Klux Klan in Los Angeles. Were they over-egging things, laying out the artist’s political affiliations in anticipation of backlash? Later, I reread the opening chapters of Night Studio. Mayer’s story of her father’s early career followed the same lines. This was the established Guston narrative. An interpretation, as all biography is, but one of some decades standing.

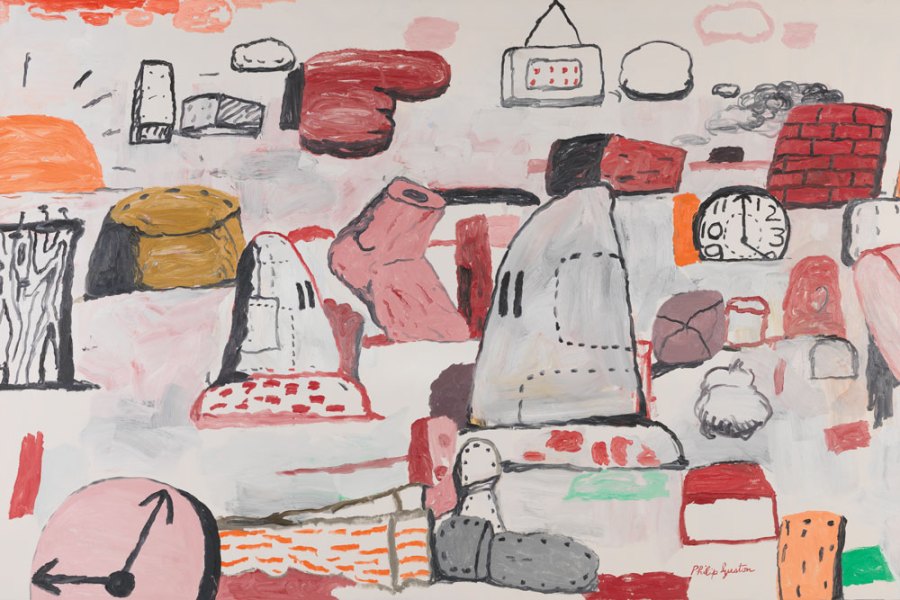

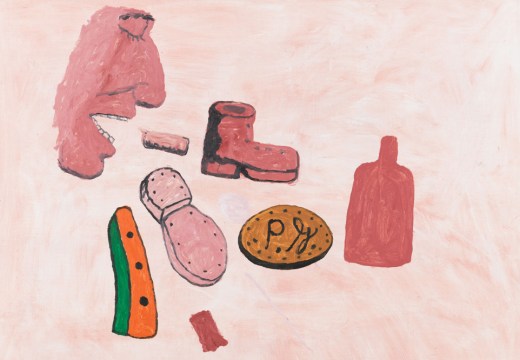

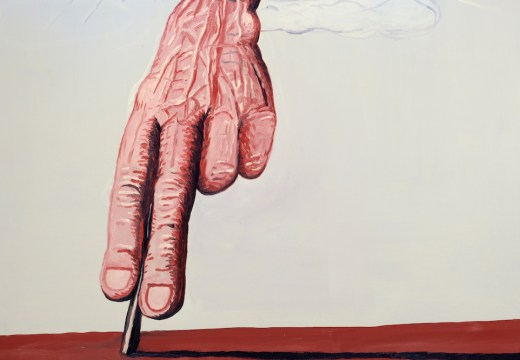

The show is phenomenally good (and I write this as someone who feels that the Tate has an extraordinary facility for sucking joy out of exhibitions). All the pre-emptive overthinking I had tangled with unexpectedly freed me to look at the painting. In Martial Memory (1941), children prepare for battle armed with the broken fragments of their built environment. This early composition, made after years of mural painting, is as tightly crammed as a 15th-century fresco. An internal struggle is followed by the wandering lines of the pale abstraction White Painting I (1951), the pulsing inner field of Beggar’s Joys (1954–55), bruised and abraded with fleshy reds and puce, and the less gestural shapes of The Return (1956–58), which are almost but not quite yet bodies. The anxious black Head I (1965) floats over a lake of sickly pinking grey. After another (long) struggle Guston returns to the figure at the turn of the 1970s – imagining himself inside a Klansman’s hood in Dawn (1970), the cartoonish horror of a car stacked with bloodstained, stiff-legged cadavers souring the peach of a summer morning. Growing old and fond, he adds his own cyclops-like head and his wife’s parted hairline to a vocabulary of forms he’s worked with since his teenage years. The show ends with them crouched under the blankets in Couple in Bed (1977), hiding from the world, Guston’s hairy arm stretched in an embrace but still gripping his paint brushes.

In his studio, the artist wrestles competing urges like Laocoön with the sea serpents. He defies the lure of success to follow his convictions and dies as acclaim reaches him from a younger generation. It’s romantic. Heroic. So old-fashioned. Is Guston the last artist to be permitted a hero narrative? If so, is that because it has become entangled and conflated with his political and moral convictions? Guston’s schoolfriend Jackson Pollock isn’t described as a romantic, heroic figure these days. Formal struggles are no longer the stuff of hero narratives for artists.

While precipitated by his response to the Holocaust, political assassinations and racist violence, Guston’s struggles and transitions are formal: from Surrealism to social realism, figuration to abstraction and then back again. He fell out with his friend the composer Morton Feldman not because of politics, but because of his apparent abandonment of modernism and return to the figure. Guston paints himself as anything but a moral crusader. In the Klansman works he imagines himself as a weak man with a weak man’s capacity for evil. Later, he’s an assemblage of crude body parts, a monocular bean with a bin lid for a shield. Guston didn’t assert the capacity of art to do good so much as lament his (and its) impotence. A hero is a fragile construct. Far better look to this Guston with baggage, flaws and self-doubt.

From the November 2023 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home