No visitor to the Foundling Museum can have missed the spectacular first-floor picture gallery. The great and the good of Georgian London look down from this, one of the first spaces for public art display in London. The room is dominated by William Hogarth’s magisterial portrait of the Foundling Hospital’s founder, Thomas Coram, now immortalised in the children’s charity that bears his name. Yet the sitter in Coram’s neighbouring portrait – an equally arresting image by Allan Ramsay – is practically unknown today.

Dr Richard Mead – physician, philanthropist, collector – was one of the founding governors of the Foundling Hospital and a well-known and well-loved figure in his lifetime. He is the subject of the museum’s final exhibition in its anniversary year: ‘The Generous Georgian’. In the 18th century Mead was Thomas Coram, Sir Hans Sloane and Dr John Radcliffe rolled into one, but he left no charity, national museum (Sloane’s collection founded the British Museum) or renowned library and hospital (one of each in Oxford bear Radcliffe’s name) to bear his legacy. He chose to focus his attention and energy on those he encountered in life, leading Samuel Johnson to comment memorably that Mead ‘lived more in the broad sunshine of life than almost any man’.

This also led, however, to the break-up of Mead’s collections after his death, in an extraordinary 56-day sale. Mead is the perfect figure, therefore, for reputation revival in an exhibition as it is precisely in the coming together of object, social history and biographical narrative that his story is compelling. The Foundling Museum have brought objects from their own collections together with others from the British Museum, Wellcome Library and Royal College of Physicians (RCP), showing precisely the division of collections and disciplines that now make Mead hard to appreciate in the round. A succession of portraits in paint, print, satire, marble and medal, as well as manuscript and print descriptions and his own published works, begin to give this multiple perspective of the man.

Three key objects all owned by Mead might serve, though, to encapsulate this generous Georgian. Mead owned a remarkable gold-headed cane that now belongs to the RCP. He inherited the cane from Radcliffe along with his Great Ormond Street House (which later became the children’s hospital) and many of his patients. It went on to be owned by three further doctors, all of whom were royal physicians, and whose names are inscribed in its handle. Mead treated such famous contemporaries as Isaac Newton and Alexander Pope, as well as members of the royal family, and worked with Queen Caroline to introduce inoculation against smallpox.

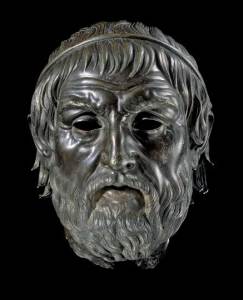

From the British Museum, the Foundling have borrowed the bronze Hellenic head of a man that was once the prize of Mead’s collection. It was then thought to be a bust of Homer, and now possibly Sophocles. The head had previously belonged to another famous collector, Thomas Howard, Earl of Arundel, and was given to the British Museum in 1760. The achievements and ideas of classical Greece and Rome were central to the mental landscape of Mead and his contemporaries. He used his extensive collection of coins and medals to illustrate his ‘Harveian Oration’ to the College of Physicians on the social standing of classical physicians.

Mead supported and collected artists and antiquarians as well as fellow doctors, charities and patients. His collection included paintings and drawings by Rembrandt, Titian, Holbein, Watteau, Dürer, Caracci, Poussin, Rubens and Van Dyck. With his library and antiques these were housed in a purpose-built gallery at the end of his garden, open to anyone curious. Mead’s support was particularly important to the artist Allan Ramsay, who painted his portrait several times. Mead supported in his studies in Italy, and may have sent patrons from among his clients. One of Ramsay’s portraits closes the exhibition, showing Mead with the bronze Hellenic head, a classical sculpture of Aesculapius the Greek god of healing, and surrounded by papers and letters from patients.

All three of these objects might evoke any of Mead’s three personas as physician, philanthropist and collector, and that in itself encapsulates him as the true 18th-century polymath whose motto was ‘not for one but for all’.

‘The Generous Georgian: Dr Richard Mead’ is at the Foundling Museum, London, until 4 January 2015.

Related Articles

Small Wonders: The Foundling Museum (Caro Howell)

Rise and Fall: ‘Progress’ at The Foundling Museum (Martin Oldham)

Review: ‘The First Georgians’ at The Queen’s Gallery (Martin Oldham)

First Look: Georgians Revealed (Moira Goff)

Affected Taste: William Kent at the V&A (Matilda Bathurst)

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home