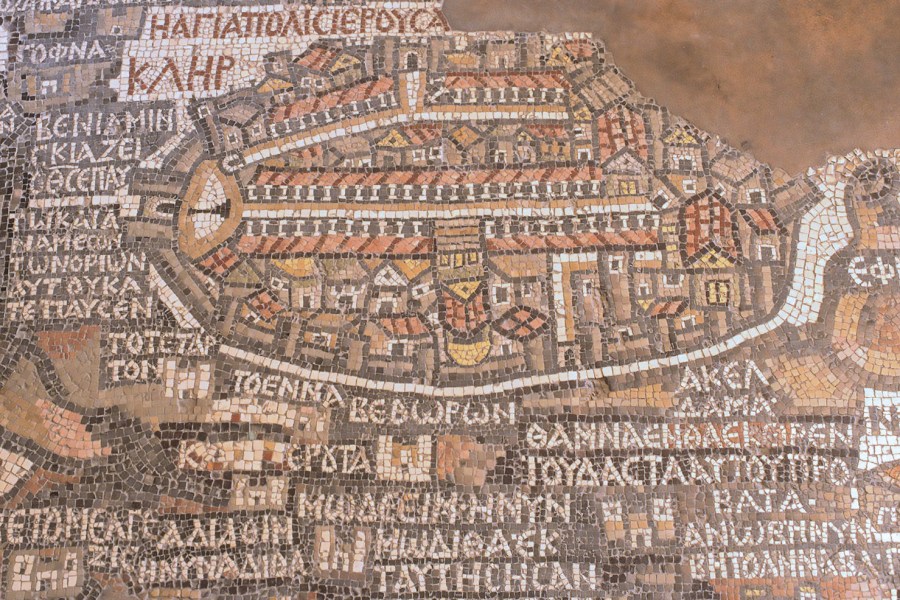

Madaba is known as the city of mosaics. An hour’s bus ride south-west of Amman, Jordan’s capital, it has one of the world’s most stunning collections of Byzantine patterned flooring, found in churches and former private houses a few minutes’ walk from each other. The most famous of them – justifiably so – is the oldest surviving map of the Holy Land, found in the modern Church of Saint George. Probably made in the mid sixth century, the Madaba Map was a stopping point for pilgrims on their way to Jerusalem. They could whet their spiritual appetite by picking out – or having picked out for them – the map’s 157 sacred sites, labelled in Greek. Some labels give a helpful precis for anyone unsure of their biblical geography: ‘Modiim now Moditha, whence came the Maccabees’; ‘Bethabara, the place of the Baptism of Saint John’.

Although the map is not cartographically accurate in terms of distances, some of the individual sites are depicted with impressive exactness. On the left side of Jerusalem, yellow stones, arranged like a mouth, represent the courtyard in front of what is now called Damascus Gate. The black pillar no longer exists but its ghost remains in the modern Arabic name ‘Gate of the Pillar.’ Moving along the central Roman cardo – the remains of which have been discovered by archaeologists in the last 50 years – we reach the central Church of the Holy Sepulchre, the dome of which is made up of a group of reddish stones.

What the Christian map-makers could not have known was that within 150 years the Islamic Dome of the Rock would become the most prominent landmark in Jerusalem. Sometime in the 630s, the Arab conquerers galloped through Madaba on their way to take Palestine. They allowed Christians to keep their religion but made them pay a special tax and restricted their worship. The map bears testimony to these religious conflicts. Two boats floating on the Dead Sea have figures riding in them – apostles perhaps? It’s difficult to tell because they have been pixilated out with white tesserae, probably on the orders of the Umayyad caliph Yazid II, who in 721 forbade images of living things. (Interestingly, such iconoclasm caught on in Christian circles: five years later, Constantinople proscribed images in religious contexts.) At least the animals survived: among them a glum fish and a pursued antelope, looking over its shoulder.

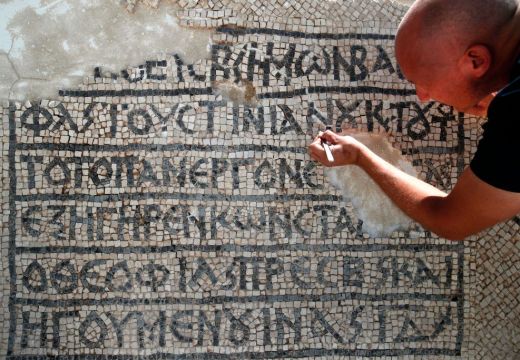

Though missing large chunks, the map is reasonably well preserved. It was discovered in the 1890s by Arab Christians who had re-founded Madaba a few years earlier. They needed a place of worship but according to Ottoman regulations a church could not be built anew – only rebuilt on an ancient site. During works on the old church, the map was uncovered. The Patriarch in Jerusalem sent the amateur archaeologist Cleopas Koikylides to investigate. On 13 December 1896, he cleared away the rubble left by workers. Stunned at what he saw, he took measure- ments and made drawings. By the next year, as we see in the first photograph, it was being protected by iron railings.

Yet apparently people still walked on and poured water over the map to brighten its colours – a deadly combination for a mosaic. By 1964, it was in a parlous state. That year, the Volkswagen Foundation granted the German Society for the Exploration of Palestine DM 90,000 to repair and restore it. The ancient lime bed was removed and replaced with a new 4.5cm-thick bed; it was covered with a transparent varnish that means its pinks, reds and yellows are remarkably vivid.

Somewhat dustier are the myth-mosaics in the nearby Hippolytus Hall. Uncovered in 1905, the floor was described by the Archimandrite Metaxakis as ‘excellent for the vivacity of its colours, the variety and beauty of its figures and the fineness of its execution’. Parts have been removed to Amman but what is left is still breathtaking.

The central panels depict Phaedra falling for her stepson Hippolytus. In the lower panel, a forlorn Phaedra, wearing a sleeveless mantle and her best pearl earrings, instructs her wet nurse to send him a romantic message. The nurse points boldly across to Hippolytus. But there is a blank space where the poor queen’s love should be: all that remains are his groom and bits of horse. In the upper panel the bare- breasted Aphrodite – who cursed Phaedra after Hippolytus rejected her – playfully smacks Cupid’s bare bottom.

On the same panel is a blossoming orange tree – a common motif in Madaba’s Byzantine mosaics and in Islamic designs at Khirbat al-Mafjar, a caliph’s palace north of Jericho. Similar floral designs are found at the Dome of the Rock and the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus. In Islamic spaces the floor is for prayers so mosaics are on walls. The early Muslims both preserved and transformed the art form, in the same way the Arabic word for mosaic, fuseefasa, derives from the Greek psifosis.

Beside a busy road is the Church of the Apostles. This large basilica overflows with gorgeous natural images: tempting bunches of grapes, a sly-looking wildcat, a chubby embodiment of spring. Slip some coins to the guard and he will take you to less-accessible images: a boy holding a parrot he has just caught, perhaps a pet, perhaps dinner. Most delightfully, a boy in a grey tunic rides a toy chariot harnessed to bemused-looking birds. The artful swirling patterns convey movement – or at least, the movement in the boy’s imaginary circus.

Detail from a mosaic (late sixth-century), Church of the Apostles, Madaba. Photo: the author

The Madaba mosaics preserve traces of the Middle East’s Greek-Christian culture that are now under threat from jihadis. (A Jordanian soldier guards the Church of Saint George.) Through them we can overhear the whispers of a lost world. In the Church of the Apostles, the family that commissioned the floor is praised: ‘O Lord God who has made the heavens and the earth, give life to Anastasius, to Thomas and Theodora.’ (Was Thomas the model for the boy with the toy chariot?) But more unusually the person who made the floor slips in his own name after theirs. ‘This is the work of Salaman, the mosaicist,’ he declares, rightly proud of his magnificent creation.

From the March issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home