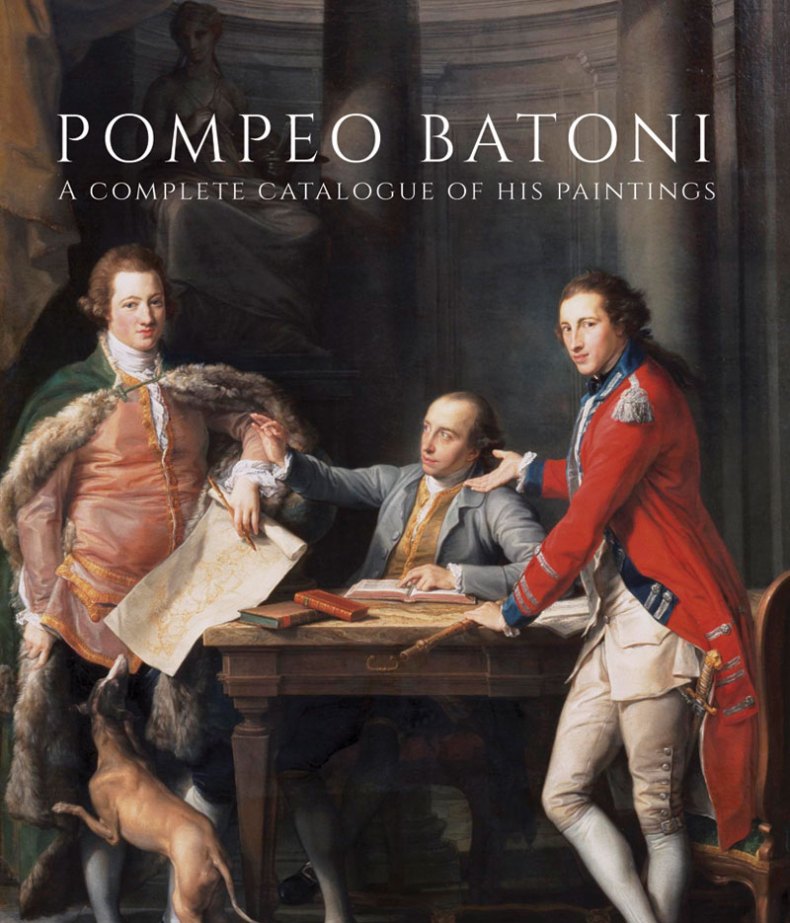

The image of the elite 18th-century cultural practice known as the Grand Tour is still defined by the polished portraits of young British male aristocrats, painted in Rome by Pompeo Batoni (1708–87). A typically sophisticated example of the artist’s portrait practice, which flatters the sitters by representing them as gentlemen of high fashion and sensitive manners who are immersed in the classical world, is the full-length double portrait of Sir Sampson Gideon, 1st Bt., later 1st Lord Eardley, and an unidentified Companion (1766–67). In an anonymous Roman palazzo overlooking the Temple of Vesta at Tivoli, the wealthy young Jewish financier, philanthropist, and adviser to the British Government sits by a bust of the Minerva Giustiniani. He is holding a letter and passing a portrait miniature of an unknown lady to a friend whose face is partly hidden in shadow, and who is standing while a greyhound paws for his attention. Batoni, who was adept at enhancing the self-imagery of the often dissolute ‘milordi inglesi’, has in this masterpiece produced a remarkably harmonious composition that is also a sympathetic reflection on the nature of male friendship.

Sir Sampson Gideon, 1st Bt., later 1st Lord Eardley, and an unidentified Companion (1766–67), Pompeo Batoni. National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Yet Batoni’s portraiture occupied only about half of his surviving oeuvre of just under 500 paintings, which are fully listed, described and illustrated – the vast majority in newly commissioned colour photography – in the outstanding new two-volume complete catalogue compiled by Edgar Peters Bowron. He has done a great deal of research on the portraits – not just of British and Irish sitters, but also of members of the local Italian elites and the princely visitors to Rome from across Europe; Bowron has also paid equal attention to establishing the extent and nature of the artist’s religious, mythological and historical paintings. These range from early altarpieces in his native Lucca through to the late studio commissions for the Basilica of the Estrêla in Lisbon. A particularly fine early example of Batoni’s compositional mastery and feeling for classical subjects is The Sacrifice of Iphigenia (1740–42), where the vivid use of lighting and colouring, and the judicious appropriation of theatrical gestures from other masters, emphasise the emotion of the terrible event about to take place. This ambitious painting was commissioned for a Welsh patron, Thomas, 2nd Baron Mansel of Margam, but its purchase by a Scottish Jacobite, David Wemyss, Lord Elcho, demonstrates that British patrons were at the heart of Batoni’s early international reputation.

The Sacrifice of Iphigenia (1740-42), Pompeo Batoni. Private collection

This masterly catalogue is the summation of Bowron’s study of Batoni within the context of high culture in 18th-century Rome and Italy. In 1985 he edited and prepared for publication the late Anthony M. Clark’s unfinished manuscript and papers on the artist. Even though that catalogue was mostly illustrated in black and white and has long been out of print, it has been the touchstone of Batoni studies for the last three decades. Bowron was also the co-curator, with Peter Björn Kerber, of ‘Pompeo Batoni: Prince of Painters in Eighteenth-Century Rome’, the memorable monographic exhibition held in 2007–08 at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, and at the National Gallery, London. Also in the tercentenary year of the artist’s birth, Bowron made a major contribution to the more substantial exhibition held in Lucca, ‘Pompeo Batoni: L’Europa delle Corti e il Grand Tour’.

The organisation of Bowron’s latest catalogue is simple and elegant. All the paintings are organised chronologically from Batoni’s early work in Lucca and emergence in Rome during the 1730s. The often lengthy entries for the paintings include archival material relating to the commissioning of the works, patronage, iconography, and art-historical analysis, as well as short biographies of the sitters to the portraits. The catalogue proper is followed by a series of useful unillustrated appendices: firstly an account of the untraced portraits, organised by subject matter, then a list of unverified paintings, organised by location, which Bowron has been unable to see or authenticate. Bowron then helpfully includes the wrongly attributed paintings, again organised by location. There is a list, also unillustrated, of around 250 drawings by Batoni, which Bowron considers to be authentic. Of particular note here is the series of over 50 highly detailed drawings copied from classical sculptures in Rome by the artist very early in his career, which were commissioned by the antiquarian Richard Topham and are now at Eton College. Bowron provides two further lists, again unillustrated: unverified drawings and, finally, what he calls ‘doubtful or rejected attributions’. As well as an exemplary bibliography and general index, there are two useful indexes of paintings by subject and by location. All that is missing is a discussion of the thorny subject of Batoni’s portrait miniatures, sorting out those by the master himself from copies that were subcontracted to professional miniaturists in Rome. As the son of a goldsmith, Batoni was capable of working in great detail on the smallest scale and of painting miniatures of the highest quality.

Princess Cecilia Mahony Giustiniani (1785), Pompeo Batoni. National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Bowron’s achievement in this latest complete catalogue is to show the exceptional range of Batoni’s painted oeuvre, throughout his long career, both as a history painter and as a portraitist to the courts across Europe. He also allows us to see Batoni as an artist of great sensitivity, as in the very late portrait of Princess Cecilia Mahony Giustiniani of 1785, which, with its lack of finish and its truthfulness, bears comparison with Goya.

Batoni was the most prestigious painter in 18th-century Rome and arguably the last baroque inheritor of the Old Master tradition going back to Raphael. He was also an artist whose production of dazzling portraiture and sophisticated religious art was central to the experience of wealthy foreign visitors to the city. Alongside Piranesi, he created the definitive statement of Rome’s cultural power and influence, an image of the Grand Tour that remains potent today.

Pompeo Batoni: A Complete Catalogue of His Paintings by Edgar Peters Brown is published by Yale University Press.

From the June issue of Apollo: preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home