British Pop art is having a resurgent moment. Last week Tate Modern announced a major Richard Hamilton retrospective for next year, which will represent the whole range of his work from the 1950s up to his death in 2011, with his role in Pop art at the centre of the exhibition via works such as the installation Fun House and the collage Just what is it that makes today’s homes so different, so appealing? (both 1956).

The Hamilton retrospective will follow on the heels of ‘When Britain Went Pop’, the exhibition with which Christie’s are opening their new Mayfair gallery in October, which will look back to the early days of British Pop with work by the likes of Hamilton, Peter Blake, David Hockney and Patrick Caulfield on display. And this year both R.B. Kitaj (an American, but one who spent most of his working life in England) and Eduardo Paolozzi have been the subject of full retrospectives at Pallant House Gallery in Chichester.

Although Pop art flourished earlier in Britain than in the US, the subsequent reputation of British Pop artists was overshadowed by the global success of the Americans. Where Jasper Johns, Roy Lichtenstein and Andy Warhol’s works are often boldly simple in conception, the work of their British-based counterparts has seemed to be more intellectual and indeed scholarly by comparison.

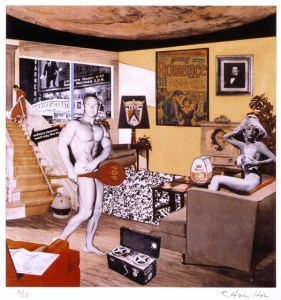

Just what was it that made yesterday’s homes so different, so appealing? (1992), Richard Hamilton © Richard Hamilton 2005. All rights reserved, DACS

Richard Hamilton spent years illustrating James Joyce’s Ulysses and reconstructing Duchamp’s Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors, Even, two of the highpoints of ‘difficult’ modernism. In the mid-1960s, when Warhol was creating his multiple images of Jackie Kennedy and Marilyn Monroe, Paolozzi was producing screenprints inspired by the linguistic philosophy of Ludwig Wittgenstein (As Is When, 1964), while Kitaj was painting pictures with titles like Nietzsche’s Moustache (1962), and would eventually come to be derided by hostile critics as an over-intellectual imposter, his wide range of philosophical and literary allusions seen as all too many alibis. There has been a suspicion, then, that the British-based artists associated with Pop were just a bit less Pop than the American boys, more likely to retreat to the library.

The Christie’s exhibition promises to show that this is not the case, or at least that if we concentrate on the earliest work by British Pop artists, we need not be dismayed by it. But anyway, perhaps the temper of the times has changed. In an era when students entering art school have no memory of a time before Google, an information-rich, allusive art which straddles text and image can hardly any longer be seen as obscure, in any simple sense. Nobody needs to actually read Ulysses or Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations for themselves to get the point of Hamilton’s illustrations or Paolozzi’s screenprints; anyone with an iPhone can get the Wikipedia cheat-sheet in a second.

And the moment seems set for a re-examination of Pop art in another way. As Hedrick Smith argued last year in his influential book Who Stole the American Dream?, the possibilities for optimism among a broad middle-class – ‘rising living standards, a home of your own, a secure retirement, and the hope that your children would enjoy a better future’ – look to be decisively over. Works such as Hamilton’s Just what is it that makes today’s homes so different, so appealing?, at once erotically entranced by and disquieted at the promises of self-improvement offered by American-style consumerism, seem to mark the beginning of a cultural era recently ended.

‘When Britain Went Pop! British Pop Art: The Early Years’ is at Christie’s Mayfair from 9 October–24 November 2013.

‘Richard Hamilton’ is at Tate Modern from 13 February–26 May 2014.

Pop-Up

Just what was it that made yesterday's homes so different, so appealing? (1992), Richard Hamilton © Richard Hamilton 2005. All rights reserved, DACS

Share

British Pop art is having a resurgent moment. Last week Tate Modern announced a major Richard Hamilton retrospective for next year, which will represent the whole range of his work from the 1950s up to his death in 2011, with his role in Pop art at the centre of the exhibition via works such as the installation Fun House and the collage Just what is it that makes today’s homes so different, so appealing? (both 1956).

The Hamilton retrospective will follow on the heels of ‘When Britain Went Pop’, the exhibition with which Christie’s are opening their new Mayfair gallery in October, which will look back to the early days of British Pop with work by the likes of Hamilton, Peter Blake, David Hockney and Patrick Caulfield on display. And this year both R.B. Kitaj (an American, but one who spent most of his working life in England) and Eduardo Paolozzi have been the subject of full retrospectives at Pallant House Gallery in Chichester.

Although Pop art flourished earlier in Britain than in the US, the subsequent reputation of British Pop artists was overshadowed by the global success of the Americans. Where Jasper Johns, Roy Lichtenstein and Andy Warhol’s works are often boldly simple in conception, the work of their British-based counterparts has seemed to be more intellectual and indeed scholarly by comparison.

Just what was it that made yesterday’s homes so different, so appealing? (1992), Richard Hamilton © Richard Hamilton 2005. All rights reserved, DACS

Richard Hamilton spent years illustrating James Joyce’s Ulysses and reconstructing Duchamp’s Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors, Even, two of the highpoints of ‘difficult’ modernism. In the mid-1960s, when Warhol was creating his multiple images of Jackie Kennedy and Marilyn Monroe, Paolozzi was producing screenprints inspired by the linguistic philosophy of Ludwig Wittgenstein (As Is When, 1964), while Kitaj was painting pictures with titles like Nietzsche’s Moustache (1962), and would eventually come to be derided by hostile critics as an over-intellectual imposter, his wide range of philosophical and literary allusions seen as all too many alibis. There has been a suspicion, then, that the British-based artists associated with Pop were just a bit less Pop than the American boys, more likely to retreat to the library.

The Christie’s exhibition promises to show that this is not the case, or at least that if we concentrate on the earliest work by British Pop artists, we need not be dismayed by it. But anyway, perhaps the temper of the times has changed. In an era when students entering art school have no memory of a time before Google, an information-rich, allusive art which straddles text and image can hardly any longer be seen as obscure, in any simple sense. Nobody needs to actually read Ulysses or Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations for themselves to get the point of Hamilton’s illustrations or Paolozzi’s screenprints; anyone with an iPhone can get the Wikipedia cheat-sheet in a second.

And the moment seems set for a re-examination of Pop art in another way. As Hedrick Smith argued last year in his influential book Who Stole the American Dream?, the possibilities for optimism among a broad middle-class – ‘rising living standards, a home of your own, a secure retirement, and the hope that your children would enjoy a better future’ – look to be decisively over. Works such as Hamilton’s Just what is it that makes today’s homes so different, so appealing?, at once erotically entranced by and disquieted at the promises of self-improvement offered by American-style consumerism, seem to mark the beginning of a cultural era recently ended.

‘When Britain Went Pop! British Pop Art: The Early Years’ is at Christie’s Mayfair from 9 October–24 November 2013.

‘Richard Hamilton’ is at Tate Modern from 13 February–26 May 2014.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

Share

Recommended for you

Preaching to the Choir

TEDxAlbertopolis promised to dispel the myth that science and art are divided. They clearly aren’t and arguably never have been

Drawn In

A new set of interactive digital displays has been unveiled at Tate Modern that seeks to create a ‘digital community within the building’

Misadventures

‘Les aventures de la vérité’ is a good opportunity squandered at the hands of Bernard-Henri Lévy