From the rooftop of the Rue de Tanger gallery, in the medina of Casablanca, rises a 20-foot lattice of steel. Designed by artist Marin Germain and Amine Slimani, the young architect who opened his gallery here in 2018 after renovating the dilapidated three-storey villa from top to bottom, Assarya (2018) takes its place in the skyline among the palm trees, the minarets and the masts of the great ships that sit in the city’s port. It is a smart bit of sculpture. Stand within it looking up, and the sky is framed by the concentric squares, which vary infinitesimally from one another in angle, size, and the thickness of the steel, locked together in what Slimani tells me is one of a million possible permutations of a parametric algorithm. Stand on the raised platform of the roof, looking north to sea, and the line where the Mediterranean meets the sky bifurcates the central square. I turn to Slimani and tell him he’s got the horizon pretty near dead centre. He chuckles: ‘It’s designed for people 1.65m tall.’

I am in Casablanca in mid June for ‘Prête-moi ton rêve’, a project that has brought together 30 leading contemporary artists from throughout Africa for a year-long exhibition. Across town, at the Villa d’Anfa (until 30 July), there is work by William Kentridge, Abdoulaye Konaté, El Anatsui, Chéri Samba – the list of superstars in contemporary African art goes on. From here, the exhibition will travel to Dakar, Abidjan, Lagos, Addis Ababa, and Cape Town, before returning to Morocco for its final iteration in Marrakech. The project has been bolstered by the establishment of the Fondation pour le Développement de la Culture Contemporaine Africaine (FDCCA) in January this year – yet Fihr Kettani, the director of the foundation, is keen to point out that it has remained essentially an artists’ initiative. The 30 artists involved, he says, have ‘worked for the most part on a Western trajectory. And the West has rendered them a great service, in terms of visibility – but the artists regretted not being known or exhibited in their countries of origin or on African territory. So they had the idea of reuniting in Africa.’

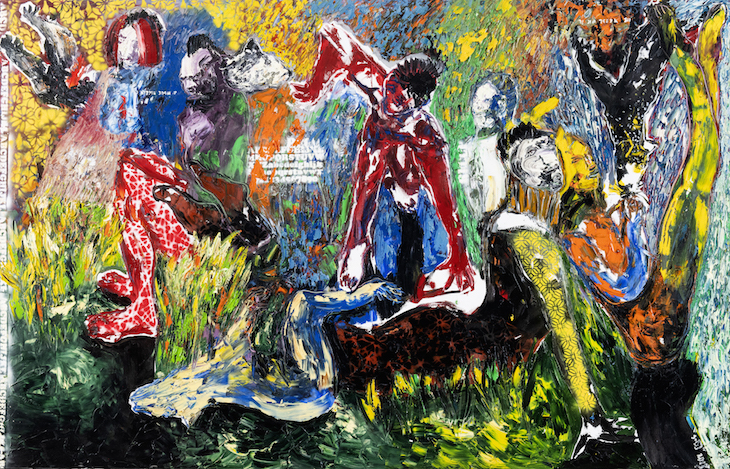

The Secret of a Little Fish Grown Large (2002), Chéri Samba. Photo: F. Maazouz

Although this is a pan-African endeavour, the organisers have been careful not to lose sight of the local. At each stop of the tour, a ‘carte blanche’ exhibition has been arranged, giving a curator from the city the chance to bring together some of the country’s top artists; the first, curated by Syham Weigant, was at the Rue de Tanger (closed 17 July), with conceptual videos and photographs by Hicham Berrada, playful resin water pistols made by Yassine Balbzioui, desert roses sculpted in metal by M’Barek Bouhchichi, and a sculpture by Mohamed El Baz that suspends two LED swords above a black map of Africa. In each city there is also an exhibition on the legacy of a local modern master; in Casablanca, Farid Belkahia was the focus of ‘Belkahia Contemporain’ at Artorium, curated by Fatima-Zahra Lakrissa (closed 19 July). The paintings of this founding father of Moroccan modernism – sometimes densely layered, abstract compositions; sometimes peopled with Paul Klee-like figures – were inspired in part by the objects and artefacts the artist found during his excavations in the Moroccan countryside. ‘Tradition is the future of man,’ Belkahia once stated. At the Rue de Tanger, his influence is plain to see – most clearly in the desert roses of Bouhchichi, but it’s there too in Slimani’s roof sculpture, which adapts the notions of ‘sacred space’ that are integral to Moroccan architecture with conceptual daring.

Across the city at the Villa d’Anfa, ‘Prête-moi ton rêve’ reveals that the alignment of tradition with modernity is also at play in the broader current of contemporary African art. Abdoulaye Konaté works with strips of traditional Malian fabrics, dyed in vivid hues by women working in Bamako, using techniques that have been handed down through the generations. Konaté arranges these strips like plumage to create vast wall hangings, combining African motifs with Western geometric abstraction. A bright red 15-footer, Tuareg Rug (2018), dominates the back wall of the Villa d’Anfa. In Iris (2012), the Ghanaian artist El Anatsui has stitched aluminium and copper together like cloth to create a glittering metal tapestry. Paintings by the Senegalese artist Soly Cissé demonstrate an expressive, gestural line that is boldly modern, yet veers away from abstraction to conjure ambiguous figures, by turns ethereal and diabolical, evoking a traditional world inhabited by shadowy spirits.

Tuareg Rug (2018), Abdoulaye Konaté. Photo: F. Maazouz

When I speak to Cissé in the sun-baked courtyard at the back of the Villa d’Anfa, he tells me that, for him, the important thing is ‘to be conscious of one’s traditional baggage, but also to propel oneself towards an exemplary future’. This ambition is evident in his paintings – but Cissé is just as concerned with how to secure an ‘exemplary future’ for young African artists, whom he feels are ‘eaten up’ by a rapacious market. They are either picked up by ‘bad galleries’, who buy work cheap to sell at a huge mark-up in the West, or forced to produce repetitive works for a tourist clientele.

These are challenges that require pragmatic solutions. For Cissé, ‘Prête-moi ton rêve’ is not only a chance for these young artists to see the highest level of art being produced in the continent – works that will ‘rest in the memory’. The cities on the tour have been chosen ‘strategically’, aiming to entice and to grow the existing network of collectors in Africa. To that end, the FDCCA has launched an African Collectors’ Club, with the aim of forging links between the key collectors on the continent and contemporary African artists. Ultimately, the hope is both that the best artwork created in Africa will remain in the continent, and that the artists will get a fairer deal.

Like Heroes (2018), Soly Cissé. Photo: F Maazouz

‘We have to work to get back our place,’ Cissé says. How effective the initiatives begun here in Casablanca might be, both for Moroccan artists and for African art at large, will become clearer as ‘Prête-moi ton rêve’ continues its journey over the next year. But it seems that this work has begun in earnest.

‘Prête-moi ton rêve’ is at various venues in Casablanca until 31 July. It then travels to Dakar, Abidjan, Lagos, Addis Ababa, Cape Town and Marrakech until July 2020.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home