Enclosed within three small rooms on the top floor of the Courtauld Gallery, ‘A Dialogue with Nature: Romantic Landscapes from Britain and Germany’ is a tiny exhibition offering a modest, academic account of Europe’s most passionate revolution in aesthetics – British and German Romanticism, as manifested in the landscapes of artists including Caspar David Friedrich, J.M.W. Turner and Samuel Palmer.

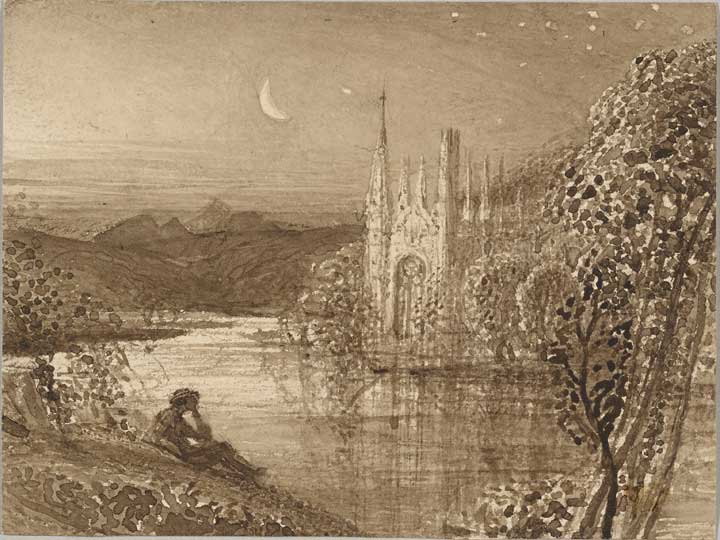

While shows such as the Tate’s 2010 ‘Art and the Sublime’ chose the more marketable monumental expressions of the Romantic Sublime – the huge canvases of John Martin or Francis Danby – this exhibition chooses to focus on what curator Matthew Hargraves describes as the ‘quiet transformation’ of landscape in the late 18th and early 19th century. In the first of a series of collaborative exhibitions between the Courtauld’s IMAF Centre for Drawings and the Drawing Institute of the Morgan Library & Museum, New York, ‘A Dialogue with Nature’ presents 26 small watercolours, oil sketches and drawings which sing rather than shout of a new vision, forged in the furnace of war, revolution, and industrialisation.

The exhibition both proposes and artfully undermines a neat distinction between the German landscapes’ ‘fastidious linearity’ and the ‘bravura effects’ of the British. Moreover, the core comparison between empirical observation of the natural world and the inventive power of the poetic imagination is beautifully skewed by the cloud studies of Constable and Von Dillis, lightly placed in a small chamber hovering between the two main rooms.

For curator Rachel Sloan, the exhibition reaches its true dramatic potential in the combination of Turner’s On Lake Lucerne, looking towards Fluelen (1841), a series of blue translucent washes scraped with a dry brush and fingernail over the glimpse of a full moon, set alongside Caspar David Friedrich’s Moonlit Landscape (1808) where swathes of shadow curve, wave-like, around a moon-shaped void – a hole sliced directly from the paper.

Blake famously said, ‘I can look at a knot in a piece of wood till I am frightened at it.’ Far from whimsy or the warm glow of perfection, the Romantic ideal was painfully wrought – the direct study of nature became a grappling with unknowable higher forces as, in the words of Ruskin, the landscape painter strove ‘to give the far higher and deeper truth of mental vision, rather than that of the physical facts.’

Echoing Blake, Samuel Palmer’s Oak tree and beech, Lullingstone Park (1828) demonstrates the artist’s fraught fascination with the oak’s ‘moss, and rifts, and barky furrows’ burgeoning beyond the level-headed observation advocated by the more commercially-minded John Linnell. For Palmer, ‘the visions of the soul, being perfect, are the only true standard by which nature must be tried’, confessing in a letter that, ‘though I am making studies for Mr Linnell, I will, God help me, never be a naturalist by profession.’

Other than references to Turner’s travels in Germany and discussion of the interactions between the German artist Jakob Philipp Hackert and John Robert Cozens as they crossed paths in Italy, the exhibition is generally wary of speculating any direct exchange of ideas between the German and British Romantic artists. The 1820s witnessed a surge of British interest in the painting and literature of the Northern Renaissance, and it is surprising that so little is made of this shared source of influence.

Palmer, on encountering works by Van Eyck, Memling and Van der Weyden at the home of the German collector Charles Aders, had promptly resolved to become ‘a pure quaint crinkle-crankle goth’ – a similar ambition is present in works by Theodor Rehbenitz and Karl Philipp Fohr. However, this exhibition is primarily about the act of looking rather than theorising, preferring to imply interrelations through subtle visual juxtapositions. As such, this simple collaboration between two institutions offers a lightness of touch and a keenness of vision rarely afforded to exhibitions boasting far-flung international loans and ambitious theoretical claims to match.

‘A Dialogue with Nature: Romantic Landscapes from Britain and Germany’ is at the Courtauld Gallery until 27 April 2014, and will be on show at the Morgan Library & Museum, New York, from 30 May to 7 September 2014.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home