Wandering through the Galleria Borghese is a heady experience at the best of times, as your senses are pleasantly assaulted by the rich array of sculptures and paintings set into sumptuous interiors. For a few months this winter the impression of sensory delight has been heightened even further by the arrival of a remarkable exhibition which explores how Renaissance and baroque artists used stone as a precious and often brilliantly colourful support for their paintings and how this Roman specialism became a highly prized European phenomenon.

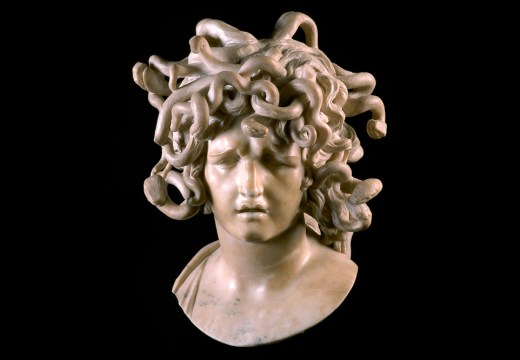

The technique of painting on stone had existed in antiquity but was rediscovered just before the sack of Rome in 1527 by Sebastiano del Piombo. It emerged from attempts to make oil paint suitable for murals; the new combination of medium and support reconciled the expressive freedom allowed by oil with the durability of stone and its appeal as a smooth surface on which to work. It was also connected with antiquarian interests in coloured marbles and the passion for semi-precious stones which was explored in a number of Italian cities in the decorative arts and church interiors, as well as early scientific fascination with classifying stones and attempting to determining their origins. The mythic and eternal associations of stone played a further role in determining its choice as a support. There was in addition to all this, the curiosity of the contribution that such works made to the paragone – the Renaissance debate about the relative merits of sculpture and painting.

Portrait of Roberto di Filippo di Filippo Strozzi (1550s?), Francesco Salviati. Private collection. Photo: A. Novelli; © Galleria Borghese

The Borghese exhibition chiefly focuses on small-scale works – cabinet pictures intended for close scrutiny by the faithful or connoisseurs, and it might be imagined that it was only with such diminutive paintings that such materials were employed. However, as the excellent catalogue points out, entire altarpieces were painted on stone. The earliest is The Nativity of the Virgin in the Chigi Chapel in Santa Maria del Popolo, which was started by Sebastiano in 1530 and probably finished by Francesco Salviati. It is painted on a form of volcanic rock found near Rome. Most altarpieces with stone supports were though painted on polished slate, quarried near Genoa, and it was slate that Sebastiano used for his portraits, examples of which feature in the exhibition. These include the austere Portrait of Clement VII (c. 1530), a candid and intense study of the pontiff, who had taken an interest in the artist’s technical innovations. Slate as a support, because of its inherent darkness, especially lent itself to the depiction of nocturnal scenes, as two later works by Francesco Bassano demonstrate: an Agony in the Garden and a Mocking of Christ (c. 1570–80), in which natural and supernatural light sources are deftly established in oil against the dense, black background to heighten the drama and spiritual import of the incidents.

The Rest on the Flight into Egypt (n.d.), Jacques Stella. Pajelu collection. Photo: A. Novelli; © Galleria Borghese

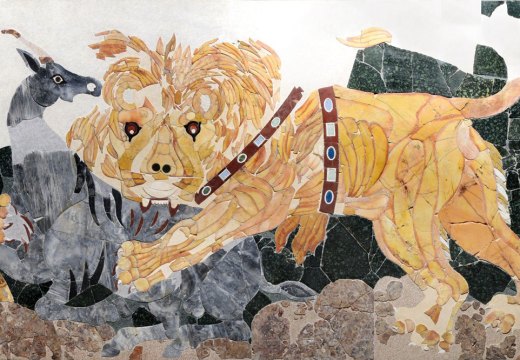

An important distinction is made in the catalogue and exhibition between painting on stone (as Bassano, for example, had) and painting with stone – in other words using the bright colours, veining and mineral properties of a chosen piece of stone to take on an active and, in some instances, defining role in a composition. A particularly beautiful example of the latter is Simone Cantarini’s Pieta (c. 1640), which is painted on Egyptian alabaster; the stone here suggests the tomb in the background, but the dramatic veining across it, like lightning strikes, also amplifies the shattering emotional intensity of the scene. By contrast with such an intimate subject, large-scale themes could also be deftly evoked by using stone, as is the case, for example, with Antonio Tempesta’s The Capture of Jerusalem (1610–20) in the Borghese collection, where the appearance of the pietra paesina (a limestone from the Appenines) on which he painted depicts the skyline of an entire city. In other works on show the features of stone come to double as cloud formations on which angels descend as well as dramatic landscapes and seascapes. The brilliant, sparkling blue of lapis lazuli, and its exotic and costly associations added further resonance to its choice as a support and the pictorial possibilities it opened up. One of the most spectacular examples of how it could be employed as a heavenly skyscape is the backdrop to Jacques Stella’s intricate Triumph of Louis XIII over the Enemies of Religion (1642) from Versailles.

Installation view of ‘Timeless Wonder’ at the Galleria Borghese in Rome. Photo: © A. Novelli; © Galleria Borghese

As wider context for all this painterly ingenuity and witty use of stone supports the exhibition includes objects of great luxury and splendour that feature chromatic inlays of marble and semi-precious stones, including a 16th-century table top, a 17th-century night clock, and most remarkable of all perhaps, from the J. Paul Getty Museum, the Borghese Windsor Cabinet (c. 1620), which has a riveting history. In 1827 it was acquired by King George IV, however it passed out of the Royal Collection in 1959, having been sold in that year at Christie’s. It is though its earlier provenance that is most relevant here, as it was in the Borghese collections in the late 17th century and is now temporarily reunited with them as part of this magnificent exhibition.

‘Timeless Wonder: Painting on Stone in Rome in the Cinquecento and Seicento’ is at the Galleria Borghese, Rome, until 29 January.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home