Considering that Richard Rogers has in the past likened his architecture to free jazz, it’s perhaps unsurprising that ‘Inside Out’ (until 13 October), the Royal Academy’s new exhibition devoted to him, should be so sprawling and – figuratively, at least – loud. The elegant Burlington Gardens space has been converted into a sort of rave tent, cramming videos, maquettes, political polemic and a pedal-powered espresso machine into three rooms that feel full to the point of spontaneous combustion. Imagine the Pet Shop Boys curating a Le Corbusier show in the Big Breakfast studio and you’re almost there.

‘Inside Out’ examines Rogers’s career in seven themes, together forming part of a personal manifesto. So, instead of a decade-by-decade performance report, we get ‘Adaptability and Change’, ‘A Place for all People’, ‘Democratising the Brief’, ‘Language of Construction’, ‘A Sense of Place and Time’, ‘Do More with Less’ and ‘Transparency, Movement and Colour’. It’s a lot to take in, and this all-inclusive postmodern curatorial order can occasionally make the exhibition – in stark contrast to the buildings themselves – feel muddled, a little confused by its own mixed messages; enthusiasm mistranslated as hyperactivity.

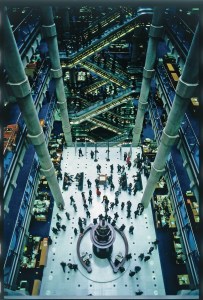

Perhaps three or four of these subheadings could have been done away with in favour of focusing on the more impassioned aspects of the show. Tellingly, the convincing sections are those that conform to the architect’s well-publicised views on aesthetics, politics and historical context; in ‘A Sense of Place and Time’, for example, Rogers makes a strong argument against stylistic conformity. Should the visitor question this approach, ‘Inside Out’ responds more than convincingly with celebratory defences of those two most iconic structures – the Lloyds Building in the City of London and the still extraordinary Beaubourg complex in Paris.

The atrium at Lloyds of London, Richard Rogers Partnership (1978–86) Image courtesy estate of Janet Gill

While ‘Inside Out’ succeeds admirably in making the case for Rogers and his collaborators as game-changers, the unreconstructed management-speak (an over-zealous deployment of the term ‘node’ is particularly irritating) and visual volume with which slogans are slammed onto the walls – BOLD CAPITALS wrestling for attention with the lurid fluorescent pink and green walls over which they are stencilled – may well give the visitor the impression that they have wandered into a giant advert for Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners. Indeed, as much space is allotted to as-yet-unrealised plans for redevelopment in London and Paris as to the earlier projects with which Rogers changed the way we think about architecture.

On the one hand, this is admirable; as the exhibition reminds us, Richard Rogers refuses to dwell on the past, to play the hits. On the other, the show’s real strengths are to be found in examinations of the completed structures – of the ingenious, semi-transparent windows of the Lloyd’s Building, say, or the house Rogers built for his parents in Wimbledon (a ‘transparent tube with boundary walls’).

Still, criticising Rogers and curator Jeremy Melvin for over-ambition feels more than a little churlish; as ‘Inside Out’ shows, Rogers has been consistently ahead of his time not only as an architect but as an urban planner and campaigner for social justice. His last Royal Academy exhibition in 1986, ‘London As It Could Be’ – a proposal for the redevelopment of public space in the city centre – was written off as impractical by local Government. As a maquette for Rogers’s Trafalgar Square masterplan shows, though, it was the architect who had the last laugh; with the exception of his royally-shunned National Gallery extension, his strategy has since been wholly adopted by Westminster Council.

This, one feels, is Rogers at his best, pushing Modernism’s guiding mantra further than the competition and making the best of contemporary possibilities better. Perhaps it is best summed up by the Ephebic Oath he claims to have adhered to since his training: ‘I shall leave this city not less but more beautiful than I found it’. Despite its flaws, ‘Inside Out’ is a fascinating reminder not only of Rogers’s brilliance, but of how architecture and planning needn’t slavishly conform to political orthodoxy and received wisdom.

‘Richard Rogers: Inside Out’ runs at the Royal Academy, London until 13 October 2013.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home