You can’t help but admire the Shed for bringing together Steve Reich, Gerhard Richter, and Arvo Pärt. The commission is a savvy PR move as much as a graceful grouping of artists. For the last quarter-century or so, Richter has been sitting at or near the top of most lists of the greatest living painters; Reich and Pärt occupy similar positions on lists of the greatest living composers. The three have lived for a combined total of some 253 years, during which they’ve amassed more or less every honour their fields offer. It is reasonable to assume that the Shed’s CEO, Alex Poots, and his co-curator, Hans Ulrich Obrist, brought them onboard not simply for their talent but for their gravitas – the same quality that is almost universally agreed to be lacking in Hudson Yards, the mammoth new Manhattan development where the Shed resides.

The resulting installation and performance, Reich Richter Pärt, boasts more than its share of gravitas. But something is missing – maybe by accident and maybe, in part, by design. There are moments when the show tantalises with its almost-sublimity, as if it’s dangling the feeling in front of you and pulling away as soon as you hold out your hand. The creators’ inventiveness, while undeniable and frequently dazzling, never fills up the dull spaces in which it unfurls – and those spaces, as much as the art or the music, are what linger in the memory.

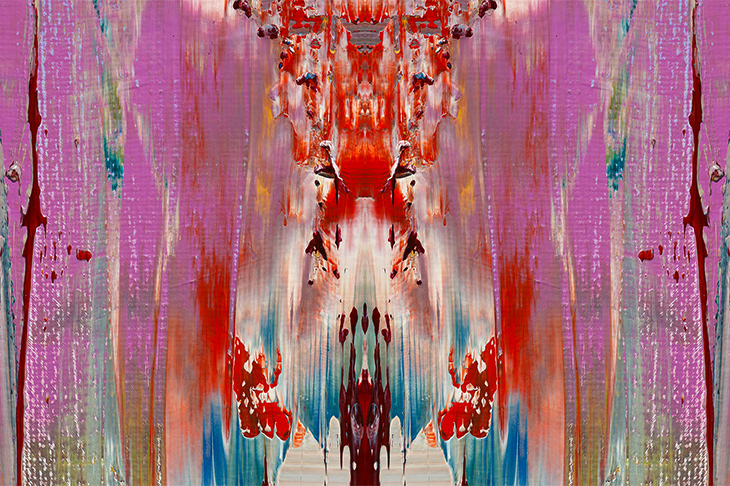

The programme begins in a large room with white walls and battleship-grey floors. On the walls, spaced a couple of feet apart, are tall, thin shafts of wallpaper covered in Richter’s designs. The images are based on details of a Richter painting, 946-3 (2016), reflected over an invisible y-axis. The results are as eye-popping as the original, but because of their symmetry they also seem carefully controlled. We are told that Richter tried to emulate medieval stained glass windows, and if true, this was either a total misreading of the performance space or an inspired prank. Stained glass windows draw the eye upward and outward, making cathedrals seem as boundless as the sky. Though similarly oriented, Richter’s wallpapers just draw attention to the concrete box they’re buried in.

If the Shed seems to be emulating the proportions and colour scheme of a murky Brooklyn warehouse, there’s something more happily warehouse-like in the spontaneity with which the show unfolds. As the audience walks around the room, a plainclothes choir launches, flash mob-like, into Pärt’s Drei Hinterkinden aus Fátima. Afterwards, patrons wander into the adjoining room, where an orchestra awaits. Only after the orchestra has started to perform Reich’s composition, and the audience has made itself comfortable, is the film component projected on to the opposite wall – forcing everyone to turn, with much groaning and muttering, 180 degrees. Little jokes of this kind pop up throughout Reich Richter Pärt. Even Pärt’s composition, rather austere on the surface, is centred around a Bible verse that translates to ‘Out of the mouth of babes and sucklings thou hast perfected praise’ – was this a wink from the 83-year-old composer?

Reich Richter Pärt (2019), Steve Reich, Arvo Pärt, Gerhard Richter in collaboration with Corinna Belz. Performance at the Shed, New York, 2019. Photo: Stephanie Berger. Courtesy the Shed; images © Gerhard Richter 2019 (05042019)

The film Richter co-directed (with Corinna Belz) is a riff on his 2011 book Patterns. Like the wallpapers, it applies the principles of symmetry to his painting 946-3 to create images of startling and slightly unsettling beauty. It begins with horizontal strips of bright colours, each one representing 1/4096th of the painting reflected back on itself. These double and quadruple into larger strips (1/2048th, 1/1024th, and so on), until you begin to recognise brushstrokes and eerie, Rorschachian shapes. In interviews, Reich has described the shapes as ‘creatures’, and his music parallels their evolution very closely, starting out with sharp, insistent 16th notes and slowing as the images thicken.

Richter and Reich’s aesthetics merge frictionlessly – at least in hindsight, pairing them seems obvious. Richter paired with Pärt, on the other hand, is anything but obvious, which is why it’s so intriguing. Pärt, a devout Orthodox Christian since the 1970s, has spent decades studying early Christian musical genres like plainsong and Gregorian chants; his works are quintessential examples of what is sometimes called holy minimalism. Richter, a self-described atheist, has spent the better part of his life painting works that, in their sinister opacity, reject the transcendent, the divine, and all the other categories Christian choral music was created to evoke.

Ensemble Signal and conductor Brad Lubman perform Reich/Richter by Steve Reich. Photo: Stephanie Berger. Courtesy the Shed

The images Richter has contributed to Reich Richter Pärt may be gorgeous, but it would be hard to mistake them for transcendent – one suspects that almost any big, complex image would yield similar treasures if it were divided into tiny pieces. The human eye can’t help but take pleasure in bright colours symmetrically arranged, and many people will conclude that the more finely divided 946-3 becomes (i.e., the less clearly it reflects Richter’s original artistry) the more beautiful the results are. The effect is similar to that of the stained glass window Richter contributed to Cologne Cathedral in 2007, made up of thousands of colourful, randomly arranged squares. The results are beautiful, whether or not you know how they were achieved – but what kind of beauty is it that can be spat out of a random number generator?

One way of interpreting Richter’s new work comes courtesy of Pärt. Drei Hinterkinden, which is dedicated to Richter, was inspired by the ‘Miracle of the Sun’ believed to have taken place in Portugal in 1917. Three young shepherd children claimed they’d been visited by the Virgin Mary, who told them that she would perform a miracle on 13 October. Tens of thousands of people showed up to witness the miracle. It’s not clear if anything happened, though several claimed to have seen bright colours.

Pärt’s composition is, in other words, a record of an event that is widely considered to have been an almost-miracle – although, one might ask, weren’t the big crowds and bright colours miracle enough? Richter’s artworks, too, are almost-miracles. By deliberately not touching on the sublime, they push audiences to embrace the beauty in painting’s constituent parts – colour and balance in particular – to an extent that few contemporary artworks can match. Even if the performance space in which Reich Richter Pärt takes place is grey and unwieldy, you could argue that this simply throws the effects of Richter’s work into starker relief. And mightn’t the big crowds and bright colours be miracle enough?

Performances of Reich Richter Pärt run at the Shed, New York until 2 June.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home