Robert Kime, the collector, dealer and interior decorator who started trading antiques from his rooms at Oxford as an undergraduate, has died at the age of 76. In 2021, Susan Moore visited Robert Kime in his London flat, a testament to his own richly varied interests in the fine and decorative arts and to his belief in the importance of creating an atmosphere. The interview is republished below.

‘I can’t help myself. I’ve been collecting things since I was five years old. I just had to,’ begins Robert Kime as he ushers me into the sitting room of his London flat. Surrounding us in its sequence of densely hung rooms is in effect a distillation of this lifetime of collecting things, for here are the survivors of an extended period of culling and downsizing. Yet, just as Kime has never been comfortable with the description of himself as an interior decorator – ‘I am an assembler,’ he says – it soon becomes evident that he doesn’t quite conceive of himself as a ‘collector’ either. No doubt the term sounds too pretentious, too precious and, above all, too studied for someone who depends so much on instinct, but his has been a life lived by the ebb and flow and romance of objects.

Kime is no serial collector. He never knows what kind of object he will be looking at or buying next – that is part of the thrill. Underlying it all, however, is an endearing modesty and egalitarianism. Calm, softly spoken and comfortably tousled, dressed in a soft linen shirt and padding around in stripy socks, the still boyish 75-year-old is as relaxed and welcoming as the rooms he creates, be they in a palace or a cottage. After our morning together, I came to recognise this same refusal – or inability – to acknowledge any distinction between the grand and the humble in the objects and works of art that speak to him and sit so contentedly together.

Kime’s acquisitive impulse, he believes, came from his maternal grandmother, Violet. ‘She was a great collector, and I loved her. There were wonderful sales during the war where she lived in Hampshire, and she was always buying wonderful stuff for very little,’ he explains, gesturing to the Imari jar on the table now serving as a lamp base. ‘It was in a flower shop that she owned, and I picked it out one day when I was 10 or 12 and she said I could have it.’ His mother continued the collecting tradition but her buying was constrained by a very tight budget. ‘When I look around the room,’ he muses, ‘I realise that I have collected things that have also been the least expensive… Nothing here is really valuable.’ One of his earliest surviving purchases, for instance, was a screen made with 18th-century Chinoiserie wallpaper, a rarity bought for a few pounds when he was 14. ‘I was thrilled with it, and I still am.’

The sitting room in Robert Kime’s flat in London, which weaves together antique textiles – including a late 16th/early 17th-century Ushak carpet – Egyptian, Greek and Roman antiquities, Chinese porcelains and Kutahya ceramics and Modern British paintings. Photo: Tobias Harvey

The ‘assembling’ bug, however, came courtesy of The Shed. Initially green and then painted black and white, this large structure stood in the garden of his Cheshire home and contained all the curious things that his stepfather had bought back with him from India. ‘He adopted me when I was one or two. I didn’t like him, actually, but he did have a good shed,’ Kime says wryly. ‘I made a room out of it. You see, I hated my house. I hated my parents and I had this shed and I lived in it and it was my refuge and my life. I created a different world from theirs. Their world was, I thought, ridiculous.’

His acquisitions fund for further companions to join him in The Shed came from the old coins he found and traded at a profit, and which also served to fire his histori- cal imagination and research – as did the buildings that he would set off to visit on his bicycle. The most magical of these, for the young Kime, was Erddig Hall in north Wales. His mother knew the famously eccentric brothers Simon and Philip Yorke, the last squires to preside over this crumbling time capsule of a house, hardly touched since the 18th century, its glories including Chinese wall- paper and embroidered silk hangings, and Soho tapestries.

Evidently precocious, Kime got into Oxford to read history at Worcester College when he was just 15 or 16. ‘I left school because I could not bear it. As Oxford did not want me until I was 18, I took myself off. I went on archaeological digs in Israel and Greece and had a really pleasurable time. I went to Italy and learned Italian and to France to learn French.’ No less enterprisingly, he continued to buy and sell what he described as pretty things when he found them, even when he went up to Oxford.

A pair of Elizabethan stone tomb figures stand sentinel at the fireplace in the dining room. Photo: Tobias Harvey

After his Prelims – university-wide first-year exams – his mother and uncle arrived and informed him that he would have to abandon his studies because his step- father had left and there was no money. His tutor, the Anglo-Saxon scholar James Campbell, told Kime that leaving was out of the question, and allowed him to ‘go down’ for two terms to sort out his mother’s affairs before returning. ‘I made one condition,’ Kime says. ‘I told him that I would have to deal in order to support myself.’ He also insisted that he keep his rooms on Staircase 7, rather than change them every year as was the custom, so that his network of dealers and collectors would know where to find him. Even then, the college bursar was none too pleased. No Oxford student today is allowed to have a job, let alone trade from one of the medieval cottages on the college premises, but trade Kime did, ‘and I used to make a perfectly good living… I have just realised it now, but that experience was the making of me. Having to make money. It was then that I had to learn everything.

‘I used to take Thursdays off and take a round trip on the bus to visit Roger Warner in Burford. On the way I would stop at six or seven other antique or bric-a-brac shops, and there were six or seven on the way back.’ Warner was a legendary dealer with an unusual penchant for antique textiles and vernacular furniture who recognised the importance of provenance. How did Kime find his own customers? ‘Oh, they found me,’ comes the quick reply. Buyers included his own college – the master’s wife was a great supporter. He sold to curators at the Ashmolean Museum and to fellow students. Among the latter were the publisher Frances Lincoln and her husband John Nicoll, who introduced him to the distinguished entomologist Miriam Rothschild, whose support launched Kime’s career as a full-time antiques dealer. (Kime went on to marry Nicoll’s sister, the late and much-missed children’s author Helen Nicoll.) As for the decorating, that developed out of friends and customers wanting homes ‘to look like yours’.

Kime has spent a lifetime making havens for himself and his family and for other people, all of which have the appearance of having grown organically and reassuringly over decades, if not centuries. Objects obviously play a role in creating these illusory palimpsests, but for Kime it is always about the specific rather than the generic. ‘A piece has got to have a resonance. I can look at something and say: “It is not for me” and wonder why it is not. It is because it doesn’t ring’ – and here he snaps his fingers – ‘there isn’t a connection. The aesthetic is important but that is not the driver. Here, let me show you some- thing…’ With these words, we go into his study to admire a 15th-century Nottingham alabaster panel depicting the Resurrection of Christ. ‘It is the sleeping soldiers that I love,’ says Kime. ‘It is the way they are asleep, curled up and crumpled, with one slumped resting on his elbow. That has a resonance, and romance, for me.’ It was one of his finds that he bought while at Oxford but kept for himself. ‘I remember it being rather expensive – it was £30 – but I am very fond of it.’

A 15th-century Nottingham alabaster panel depicting the Resurrection hangs in one corner of the study below a carved Elizabethan text-plaque from Longleat House. Photo: Tobias Harvey

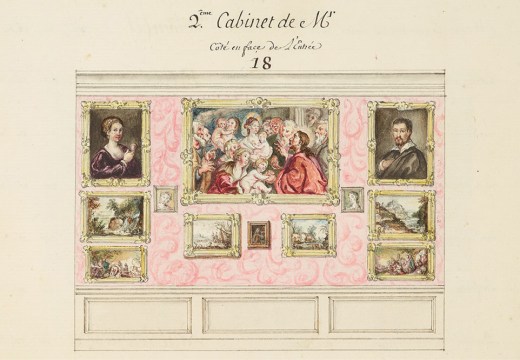

If Kime could be pigeonholed as a collector, it would perhaps be as an antiquarian of the Elias Ashmole school. This flat is a veritable cabinet of curiosities embracing specimens and depictions of the natural world as well as the quirky, intriguing and usually anonymous survivals of humanity produced over millennia. ‘That I love,’ he enthuses, for instance, opening a box to extract a large and beautifully mottled flint knife that nestles comfort- ably in one’s hand. The crib inside the box reveals that it had been dug up under the prehistoric stone temple at Avebury in Wiltshire and was ‘considered to be one of the finest examples of British flint work known’. (Opposite hangs a brooding painting of that other famous henge before its great stones were re-erected.)

Decidedly unlovely is an immense bezoar as heavy as a rock which, in its day, was highly prized as an anti- dote to poison. This calcified growth would have been found in the stomach of some large ruminant, and Kime points out the marks where it had been scraped for use, perhaps for the French king who was said to have owned it. Beside it sits another richly allusive relic, a fragment of the Parthenon. The whole place is alive with historical reverberations.

Kime opens the glass doors to a cabinet and picks out a half dozen objects seemingly at random from its eclectic jumble. Among them are a marble kneeling prayer figure from an Elizabethan tomb, a small Ptolemaic-period Egyptian bronze animal sarcophagus bearing statues of five little cats – ‘I am fond of it’ – and a red-figure kylix or tazza painted with a satyr looking for something in a large chest which surreally conceals half of his body. When I say that I have never seen anything like it, Kime answers ‘Neither have I!’

A mid 19th-century English School painting of the Great Pyramid of Giza hangs above a painted wooden boat and figures from Middle Kingdom Egypt. Photo: Tobias Harvey

Closer inspection reveals many seemingly familiar things to be out of the ordinary. A Charles I mirror frame, for instance, is a great rarity, decorated with scrolling leaves and baskets of flowers confected not out of embroidered stitches but tiny curls of coloured and gilded paper. In one of the panels of 17th-century stumpwork embroidery – in which the figures are raised by padding to create a three-dimensional effect – a Black maid is in attendance on the royal family. Elsewhere, costly stumpwork is simulated on a humble painted wooden box, and all the more unusual for that.

Even more compelling is an intriguing provincial Elizabethan portrait dated 1601 and found in Wales, and where neither the artist nor the sitter is known. Its subject bears the attributes of the hedger and ditcher, yet he is dressed in finery, with a silver belt and silver thread in his breeches. The Latin rubric translates as ‘Because the father believed the woman’. Does the half sun suggest that the man is just that, half a son, the natural son of a peas- ant and a gentlewoman, or has he been cheated out of his inheritance by a second wife? Was it commissioned by the unhappy subject himself, or by someone else? Hanging on the back of the screen opposite is a 17th-century garment of comparable stuff – the surprisingly heavy green and red facecloth tunic of a Sherwood Forester trimmed with silver braid, which came from Roger Warner.

Fabrics, as these photographs reveal, are very important to Robert Kime, but most especially carpets. He thinks he was about 12 when he bought his first rug. Most of the important pieces are displayed on the wall, like a 17th-century Ushak and a later ‘Holbein’ carpet that hangs as its pendant in the hall, or a large 17th-century prayer kelim from Aleppo behind an Arts and Crafts desk (which, like William Wordsworth’s chair, sits on a William Morris carpet). When I lament that it is almost impossible to discover anything any more – he has just pointed out a pair of Elizabethan tomb figures that had been sitting in a garden in Somerset about 25 years ago – he quickly responds: ‘You do still find things but not in the same places… For instance, I buy truly wonderful carpets very inexpensively, from – where do you think? – Christie’s.’ Kime is making the most of the tumbling market for carpets.

An Elizabethan portrait dated 1601, its subject in the clothes of a gentleman but bearing the attributes of a labourer. Photo: Tobias Harvey

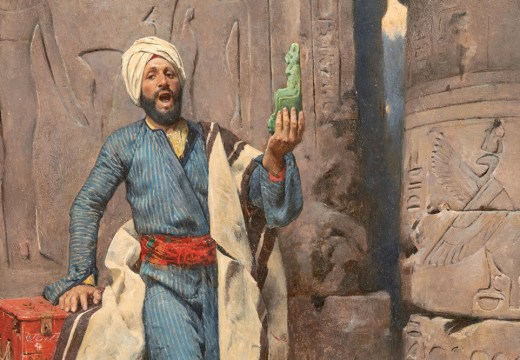

Egypt is in evidence everywhere. ‘I did not understand Egypt until I went there,’ Kime says. ‘It was a revelation. I used to love Greek and Roman stuff, but this material is thrilling.’ He liked it so much he had a house at Fayoum for a time, and it launched his appreciation of Edward Lear watercolours (he also has a particular fondness for Ravilious, Paul Nash, Sickert and William Nicholson).

Another great thread running through these rooms – in addition to books – is comprised of blue-and-white porcelain, most but not all of it Chinese. This ribbon occasionally erupts into a great mass of vessels, piled on the top of a 19th-century Gothic press in his bedroom still bearing its original drab paint or across the kitchen cabinets. A monochrome garniture of blanc de Chine similarly runs across the chimneypiece in the sitting room. I ask if this porcelain mania was a phase. ‘Oh, yes, but I have not grown out of it yet.’

It seems unlikely that Robert Kime will ever grow out of any of his phases. As we leave the building, he expectantly rips the wrapper off the Antiques Trade Gazette waiting on the post table in the hall and tucks it under his arm. He pauses to muse: ‘What I have been trying to put into words, but I have not quite got it straight in my mind yet, is that I think I am trying to create an atmosphere. It is an atmosphere that I did not have as a child and I needed. Yes, I think it is all about atmosphere.’

From the December 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home