Leo Frobenius (1873–1938) might be called the Indiana Jones of German ethnography. In the course of 12 expeditions that included extensive travels in southern, northern and Saharan Africa, Frobenius and his team ventured to some of the most inaccessible, unmapped landscapes in the world, frequently digging their vehicles out of sand and improvising repairs to broken axles. Their discoveries transformed understanding of the earliest recorded human culture.

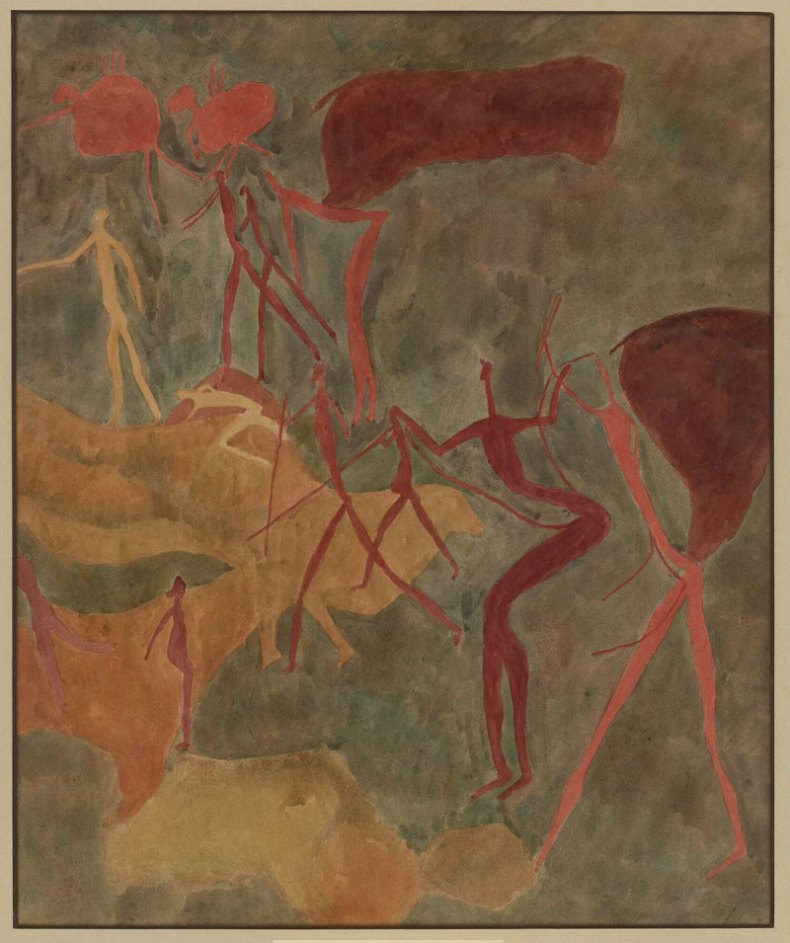

In caves and on the walls of rock shelters, Frobenius found images dating back tens of thousands of years, where human figures jostled for space with big game creatures, hand prints, and mysterious patterns of dots. Some were large-scale hunting scenes covering entire walls, with dozens of human and animal participants. Others had a startling directness of line, their unknown creators reaching across unimaginable distances of time to make the creaturely being of their subjects vividly present.

As an anthropologist, Frobenius’s aim was to devise a systematic theory of how representational styles migrate between cultures – a study which he christened ‘Kulturmorphologie’. Although highly sympathetic to African culture, Frobenius inevitably brought to bear some of the assumptions of a European man of his era; the views of Africans and their worldwide descendants on his work have been mixed. In 1946, African-American writer and campaigner W.E.B. Du Bois described Frobenius as ‘a great man and an eminent thinker’ who ‘regarded Africa with unbiased eyes and was more useful for the understanding of black culture than any other man I have met’. Conversely, in his Nobel Prize acceptance speech of 1986, Nigerian dramatist Wole Soyinka criticised Frobenius’s ‘schizophrenic’ ability to value the prehistoric art of the Yoruba while denigrating their modern-day descendants; Frobenius, he concluded, was a ‘notorious plunderer’ who had issued ‘a direct invitation to a free-for-all race for dispossession, justified on the grounds of the keeper’s unworthiness’.

‘Art of Prehistoric Times: Rock Paintings from the Frobenius Collection’, the richly interesting exhibition at Martin-Gropius-Bau in Berlin, brings a less heralded aspect of Frobenius’s project to light. In the era before colour photography, Frobenius’s main way of recording his discoveries was in paint; on each expedition he was accompanied by a team of artists whose job was to create full-size watercolour facsimiles. With the artists working in inhospitable conditions, from faded, partially obscured originals painted on uneven, three-dimensional surfaces, the task of producing clean, flat copies on paper demanded painstaking work and considerable imaginative leaps. Frobenius understood the nature of the challenge when he said that the work ‘can be done satisfactorily only by those who have, so to speak, immersed themselves in the material and are sensitive to the spirit and mentality of an age which has passed’. The artists, many of whom were women, were left uncredited in early exhibitions, but in ‘Art of Prehistoric Times’ the creators of the copies are given their due; the most important of them were Elisabeth Mannsfeld, Agnes Schulz, Maria Weyersberg, and Joachim Lutz.

‘Art of Prehistoric Times’ is therefore engaged with two histories at once. There is a history of representations marked on to rock in a period stretching back up to 40,000 years, about which we know almost nothing for sure. Then there is the history of how the modern West discovered, copied, and received these creations. In large part, the first history is only accessible through the second, and this exhibition is especially interesting in its reflections on the influence of prehistoric rock art on modernist painting.

When Joan Miró declared in 1928 that ‘since the age of cave painting, art has done nothing but degenerate’, he expressed a widely shared sense of the nowness of these works. Many prehistoric rock painters manipulated perspective and dynamic relationships between elements in the composition, or attempted ‘all-over’ composition in unframed murals, in a manner that strikingly anticipated the work of early and mid 20th-century artists.

When these copies were exhibited around the world in the 1930s and ’40s, the similarities between modern painting and prehistoric rock art caught the public imagination. The Milwaukee Sentinel illustrated its review of one of the Frobenius exhibitions in 1937 by juxtaposing Paul Klee’s Little Experimental Machine (1921) with a rock art copy from the Libyan desert showing six ostriches, asking their readers, ‘Can you tell which is which?’ The headline put the matter directly: ‘First Surrealists Were Cavemen.’

The art of rock-art copying had a short lifespan. Once it became possible to take colour photographs at the required size and quality in the 1960s, painted copies became obsolete. Yet the feeling one gets from ‘Art of Prehistoric Times’ is that these inauthentic, handmade copies may be truer representations than modern photographs. The painted copies never let us forget that we have access to the deep past only through the mediation of modern subjectivity.

‘Art of Prehistoric Times: Rock Paintings from the Frobenius Collection’ is at Martin-Gropius-Bau, Berlin, until 16 May.

From the March issue of Apollo: preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home