Edinburgh City Council recently announced plans to reconsider the future use of Thomas Hamilton’s Royal High School on Calton Hill, ending a deal with developers who had pledged in 2009 to find a sustainable purpose for the building. The High School, a masterpiece of the Scottish Greek Revival, has long lain empty; in 2015 plans to transform it into a luxury hotel were widely condemned by heritage groups and the public, and last year the Scottish Government rejected a revised proposal.

The council’s decision has been welcomed by the Royal High School Preservation Trust, which since 2015 has campaigned for the building to become a new home for St Mary’s Music School. The trust is likely to make a bid to take over the site, while the hotel developers have yet to confirm whether they will submit a further proposal. In the April 2015 issue of Apollo, Gavin Stamp discussed the significance of Hamilton’s building and lamented that it might become a hotel; an adapted version of this article is republished below.

‘Iconic’ is a much-abused adjective, particularly when applied to buildings – so much so that I only ever employ the word in inverted commas. James Stevens Curl gives a good definition in the new edition of the magnificent and essential Oxford Dictionary of Architecture: ‘iconic: 1. of or pertaining to an icon; 2. work of architecture uncritically admired: the term is so over-used (and misused) as to be almost meaningless.’ There are, nevertheless, a handful of buildings that are of such symbolic importance and so revered that they might with justice be called iconic. And, just as an icon loses much of its power and significance if taken from a church and preserved in a museum, so such buildings are somehow demeaned if adapted for a different and lesser function.

One such building is the New Palace of Westminster with its clock tower, recognisable throughout the world as a symbol for London, for the United Kingdom, for parliamentary democracy. This is why the wartime parliament quickly decided to rebuild the House of Commons in the same shape and style after it was destroyed by bombing in 1941, and why it is so distressing to learn that this great work by Barry and Pugin has been allowed to get into such poor condition that it may have to be abandoned by our elected representatives, if only temporarily. William Morris, in his News from Nowhere (1890), imagined that in his ideal socialist future the Houses of Parliament would be redundant and used as ‘a sort of subsidiary market, and a storage place for manure’ – but we must hope it won’t come to that.

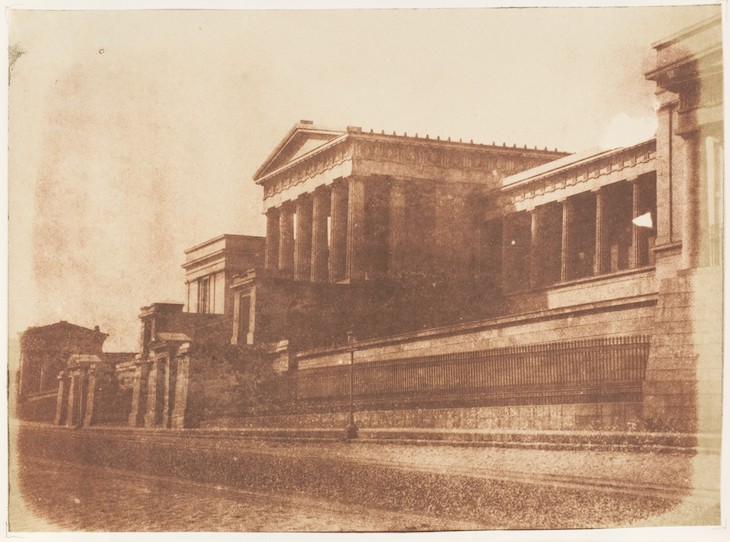

Another such architectural icon is surely the former Royal High School in Edinburgh, a building that might have become the home of another parliament because it is so architecturally impressive and symbolically powerful in its context. If that had come to pass, its iconic status would have been, as it were, upgraded. As it is, there is now a real chance it will be downgraded. Built after much debate and at great expense on the flank of Calton Hill, Edinburgh’s acropolis, in 1825–29, it is the masterpiece of the architect Thomas Hamilton and one of the finest essays in the Greek Revival, that austere neoclassical manner which had been adopted by the Scots (more than by the English) with great enthusiasm. While Edinburgh was already known as the ‘Athens of the North’, not because of its buildings but because of the great minds that dwelt there, such architecture came to represent the city’s intellectual character. For the Glasgow architect, Alexander ‘Greek’ Thomson, it was one of ‘unquestionably the two finest buildings in the kingdom’; a century later Sir John Summerson described it as ‘the noblest monument of the Scottish Greek Revival’.

The old Royal High School photographed in 1843–47 by David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

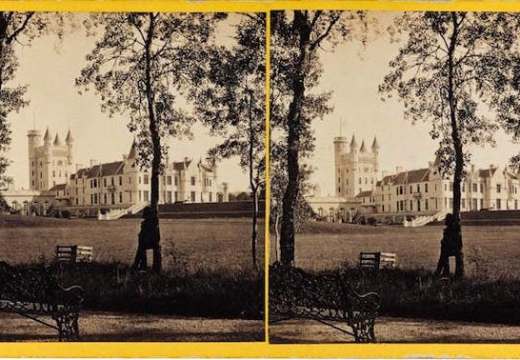

In 1968, the school moved out to the suburbs, leaving Hamilton’s building empty. A decade later, at the time of the first Scottish devolution referendum, and thanks to the monumental authority of its architecture and to its magnificent elevated site overlooking the city, the High School building was chosen as the home of the proposed Scottish parliament and the central block was converted into a debating chamber. No transfer of power came to pass, but the building then became a focus of nationalist protest. When the idea of Scottish devolution was revived in the 1990s, a fine parliament house was therefore ready to go. But Donald Dewar, the Secretary of State for Scotland, had other ideas; he allegedly dismissed the High School as a ‘nationalist shibboleth’ and determined that the Scottish Parliament be built on a low-lying and symbolically curious site opposite Holyrood Palace.

Meanwhile the old High School stood glorious and redundant. What to do with so important and prominent a listed building? In 2003 it was proposed to make it into the Scottish National Photography Centre – particularly appropriate, since those Scottish pioneers of photography, David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson, had printed their calotypes in nearby Rock House – but this admirable scheme was scuppered by Scotland’s third First Minister, Jack McConnell. So in 2008 the City of Edinburgh Council, which now owns (and, it transpires, neglects) the empty High School building, began a marketing exercise to find a new use for it, establishing a development brief to ensure that its architectural integrity together with the views to and from it were respected. The council eventually selected Duddingston House Properties, who propose to make the High School into a luxury hotel.

Hotel use can certainly respect and even enhance the integrity of a historic building, and has the benefit of public access. The problem is that the High School building is nowhere near big enough to house enough bedrooms to make it commercially viable as a hotel. The architect Gareth Hoskins therefore proposes to add two large detached wings containing 150 bedrooms. This scheme, which ignores the firm advice of Historic Scotland, will destroy the splendid isolation of the High School on the side of Calton Hill. Worse, perhaps, is that it is proposed to make alterations to the exterior of Hamilton’s great temple of learning, a superb composition of porticoes, colonnades, pavilions and long blank stretches of Craigleith stone walling, perfect for its rocky site. As Historic Scotland once advised, ‘the exterior of the High School should be treated as a work of art. It should not be altered or extended in any way that changes its appearance, form, or massing.’ Yet Hoskins proposes to replace Hamilton’s deliberately blank podiums with a banal flight of stairs. This can only be described as iconoclasm. It now remains to be seen whether Edinburgh Council will yet again surrender to commercial pressures or will insist on a more appropriate and less destructive use, such as this austere, resonant architectural symbol of the Scottish Enlightenment surely deserves.

View of the Royal High School and Burns’ Monument, Edinburgh (c. 1830), Thomas Allom. Photo: Chris Park; courtesy the Royal Scottish Academy of Art & Architecture

Lead image: used under Creative Commons licence (CC BY-SA 3.0; original image cropped)

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home