Before John Bellany (1942–2013) visited Buchenwald concentration camp in 1967 his work had given a more or less naturalistic account of the Port Seton fishing community in which he grew up (although Allegory, a 1964 triptych presenting the gutting of a haddock as the crucifixion was maybe a sign of things to come). But the apparent proof of man’s basic sinfulness he found in Weimar, intimations of which had haunted him since his Calvinist upbringing (see, the haddock), prompted a series of works addressing the savagery of human existence. And his The Ettrick Shepherd (1967) forms the implied centrepiece of ‘The Scottish Endarkenment’, a new exhibition at Edinburgh’s Dovecot Studios.

The Ettrick Shepherd (1967), John Bellany. ©The Estate of John Bellany. Photo: Stuart Armitt, courtesy Dovecot Gallery and Fleming – Wyfold Foundation

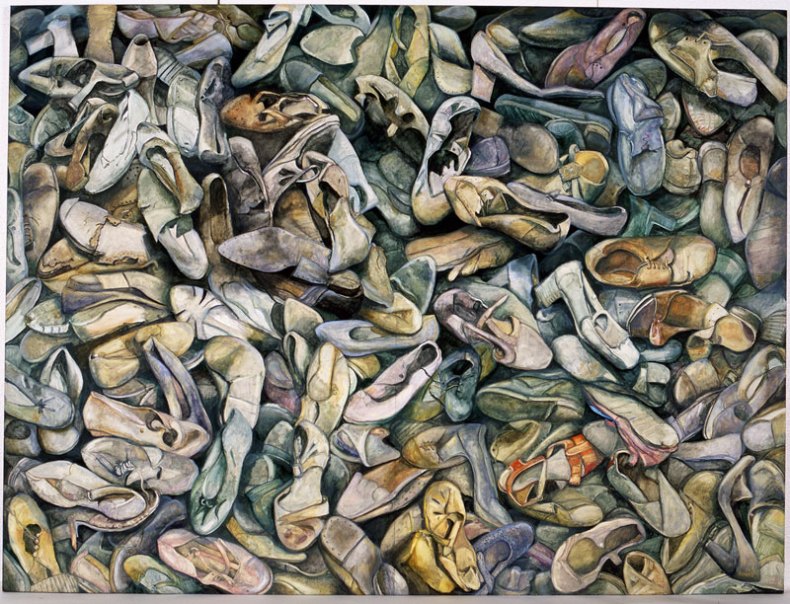

The curators have identified what they call a ‘shared concern with a wide range of disturbing psychological and social issues’ among Scottish artists since 1945. Their title, of course, sets this collection of works by over 40 artists, from William Johnstone to Eduardo Paolozzi to David Shrigley, in playful opposition to the 18th-century Scottish Enlightenment and its apparent faith in human reason. You needn’t look much beyond Shoes from Majdanek (2005) by Joyce Cairns, a large, sallow painting of a heap of Holocaust victims’ shoes, which nevertheless nestle and sprawl and sit atop one another with the stolen variety of their owners, to understand why this faith might have dimmed in the aftermath of the Second World War.

Shoes from Majdanek (2003), Joyce Cairns. © The artist. Photo: Stuart Johnstone, courtesy the artist

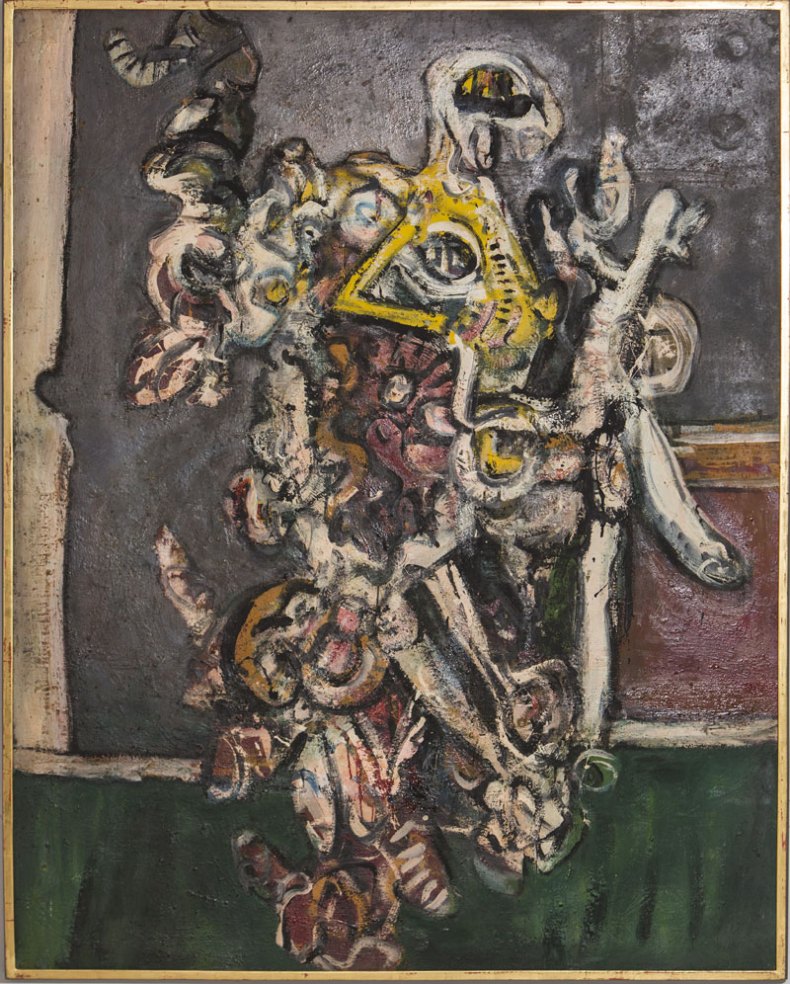

‘The Ettrick Shepherd’ was a nickname given to James Hogg, in whose The Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner (1824) a delusional narrator attempts to square his mortal sins with his Calvinism. If there was a peculiarly Scottish response to the horrors of the 20th century, the curators argue, it would lie in this ‘dialectical struggle within the Scottish psyche between good and evil’. In Bellany’s painting – on show in the North Gallery, amid other pieces that ‘share a concern’ with questions of ‘the self and personal identity’ – the cadaverous subject is dwarfed by his shadow, cast against a dark baize background.

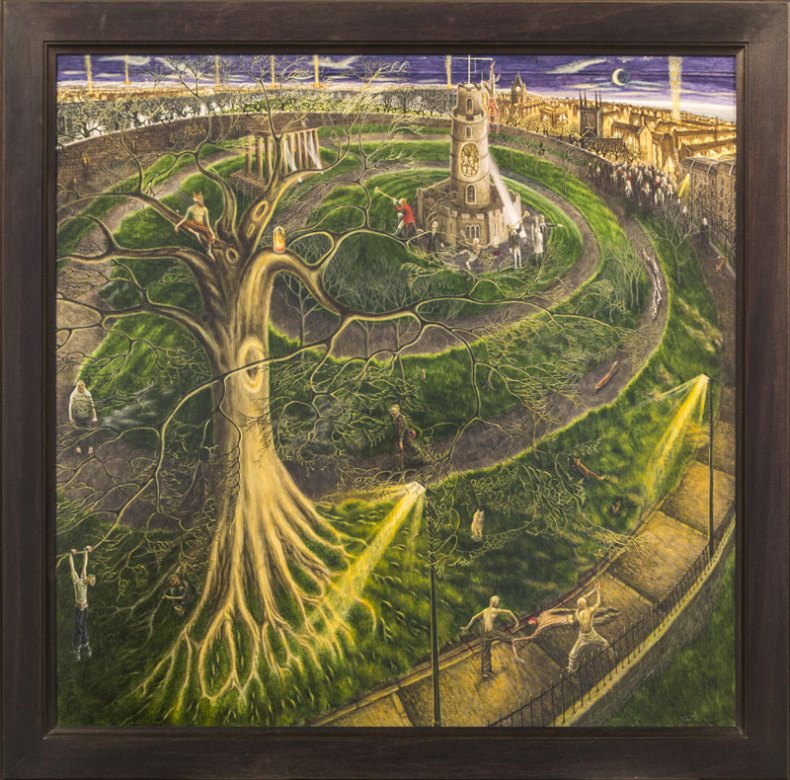

Calton Hill (2014), Jock McFadyen. © The artist

Sin casts its shadow, and so does history. The larger South Gallery is given over to artists who share ‘political, historical and social concerns’. But amid the sculptures of mushroom clouds or predictable critiques of late capitalism and 18th-century colonialism it is difficult to identify what concerns Jock McFadyen’s Calton Hill (2014) shares with Alan Davie’s captivating Woman Bewitched by the Moon No. 2 (1956). In McFadyen’s work, a massive moon looms, thick with paint, out of the canvas and over the depiction of Calton Hill’s neoclassical monuments, that would otherwise be expected to dominate an Edinburgh skyline; while Davie’s painting is a writhing fugue of anthropomorphic shapes, as if a cubist work had been infected with expressionist spores.

Woman Bewitched by the Moon No 2 (1956), Alan Davie. © The Estate of Alan Davie. Photo: Stuart Armitt, courtesy Dovecot Gallery

They begin to make more sense when you consider them as a piece with Peter Thomson’s Little Foxes (2009), a moonlit depiction of attacks on gay men in Calton Hill, where half-human creatures mingle with crucifix-wielding thugs. The paintings appear in sequence, and each of their moons loom, in a mythic sense, as a symbol or even a cipher for unsettling and often communal pre-rational urges. For all the curators protest that they don’t ‘direct the viewer to any definite conclusion as to the meaning of what is on display’, this is not the only place where their selections seem to provide a reductive key to themselves.

The Little Foxes (2009), Peter Thomson. © The artist. Photo: Stuart Armitt, courtesy Dovecot Gallery

We find Bellany’s Ettrick Shepherd not far from Lys Hansen’s Grip (1985) – the central panel from her ‘Divided Self’ trilogy, that title a reference to the controversial Scottish psychiatrist and countercultural hero R.D. Laing. (About whom, Luke Fowler, another of the artists on display here, made a 2011 film, All Divided Selves). According to Laing’s 1960 book The Divided Self, it is the repression of what we suppose to be our irrational impulses that makes us mad – those impulses being in a sense rational responses to a mad and violent world. The point is suspiciously neat, and the relationship between some of the wonderfully diffuse pieces here and the exhibition in which they find themselves seems a little like the face depicted in Grip, which is at once bruised and pale and blushing, a multiplicity of strokes and shifting expressions, slipping out and away from the fat fingers straining to get a hold of it.

The Divided Self: Grip (1985), Lys Hansen. © The artist

The Scottish Endarkenment: Art and Unreason 1945 to the Present is at Dovecot Studios, Edinburgh until 29 August.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home