Braving the scorching heat of the Georgian summer, on 4 August an unlikely crowd of bespectacled academics, young activists and assorted art lovers assembled in front of the Shalva Amiranashvili Museum of Fine Arts, Tbilisi, to protest about the threats that have emerged to Georgia’s most significant museum. The 1,000-strong crowd stood beneath the building’s massive pediment, releasing black smoke, making speeches and signing petitions calling for the preservation of both the building itself and its priceless collection of more than 139,000 objects.

The Art Museum, as it is known throughout the city, is literally a treasure house. It boasts the so-called Golden Fund, a repository of Christian art from the Golden Age of medieval Georgia from the 11th to 13th centuries: solid gold repoussé chalices, processional crosses, cloisonné enamels and scores of exquisite icons that have departed from the stiff formalism of Byzantium for a devotional art that feels expressive and alive. As if that wasn’t enough, the museum encompasses a superb collection of Islamic arts, including the most extensive collection of Qajar portraiture in the world; and the crown jewels of Georgian modern art, the work of the self-taught Georgian master Niko Pirosmani and his contemporaries.

Inside the Shalva Amiranashvili Museum of Fine Arts, Tbilisi (photo published in the Caryatid report of July 2021)

Inside the Shalva Amiranashvili Museum of Fine Arts, Tbilisi (photo published in the Caryatid report of July 2021)

Sadly, most of these exhibits have either been closed to the public or housed elsewhere for more than a decade – the Pirosmanis at the National Gallery of Georgia, for instance – as the museum’s building, a vast neoclassical edifice from 1835, has been allowed to decay. The Golden Fund remained open until 2019: housed in an increasingly dingy basement and patrolled by unreceptive museum guides of a type that will be familiar to any visitor to the Hermitage in the 1980s. A gradual decanting of the exhibits was meant to be followed by a comprehensive renovation of the building, for which for many years a plan has been in place, co-authored by specialists from the Smithsonian and elsewhere.

The fate of this plan, and of the museum itself, was thrown into doubt on 20 July, when the institution’s new director, Nikoloz Akhalbedashvili, called a meeting of the senior curatorial staff, collection managers and gallery attendants – more than 20 people were present – and made a devastating announcement. ‘He said that we must start the evacuation of all the objects,’ says Nino Khundadze, curator of modern and contemporary art, and keeper of the Pirosmanis.

‘He said he didn’t know where the objects should be taken, but that we must start the evacuation immediately and that it must be done very quickly,’ the urgency due to the parlous state of the museum’s building. The entire collection needed to be evacuated within six months, Akhalbedashvili told the meeting – an unfeasibly brief window for such a complex operation.

‘We asked what would happen with this building,’ Khundadze says. ‘And he said it is not the museum’s building any more. He said reconstruction of this building would be unprofitable, that we must give it to the ministry of economy – and what they do next we have no idea about.’ (Georgia’s ministry of economy and sustainable development is the body tasked with selling off state property).

Akhalbedashvili, a lawyer with no experience in museum studies, was appointed directly by Georgia’s new minister of culture, Tea Tsulukiani, in May this year. Tsulukiani, who also has no experience in arts and culture, is known for her hardline stance and fierce loyalty to billionaire oligarch Bidzina Ivanishvili, the country’s former prime minister (and its richest man), and the owner of a vast new glass and steel complex next door to the museum. Their connection has prompted many to speculate on the eventual plans for the museum site.

As news from the meeting leaked to opposition-minded media, Tsulukiani stepped in, calling the reports fake news, and castigating the museum administration as being responsible for the poor condition of the museum building. Ominously, her statement referred to a document prepared by a hitherto unheard-of company, Caryatid, that had provided the ministry with ‘expert analysis’ on the state of the building. The report recommended that large parts of the building would have to be destroyed, as renovating them would not be ‘commercially viable’.

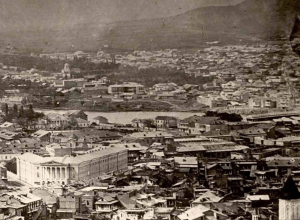

Archive photograph of Tbilisi, showing (bottom left) the building later home to the Shalva Amiranashvili Museum of Fine Arts

Tbilisi has seen vast numbers of new developments in the last 10 years, with dozens of neoclassical and art nouveau treasures being lost to the wrecking ball, but the threat to museum is of a different category. It is among the oldest secular buildings in Georgia, and one of the first works of neoclassicism in the Caucasus. It is also historically significant, as the location of the Orthodox seminary in which Joseph Stalin (né Ioseb Jugashvili) was introduced to Marxism (he was subsequently expelled). It became a museum in 1953, the year of Stalin’s death, and since then has taken on a role that – by way of international comparison – combines the functions of the National Gallery and V&A in one building. News of its potential demolition was greeted with horror.

The public outcry appears to have had an effect. Speaking on 3 August, Tsulukiani denied there had ever been a plan to destroy any part of the building. Directly contradicting what her appointee Akhalbedashvili had told museum staff at the meeting on 20 July, she said the museum and all its exhibits would move back into the building once renovation was complete.

In spite of this apparent victory, the museum community in Georgia has little faith in its minister of culture. The ministry still appears determined to remove the collection in the next six months, a plan dubbed ‘unrealistic and unworkable’ by the Georgian chapter of the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS), the Georgian chapter of the International Council of Museums (ICOM), and the Georgian National Committee of the Blue Shield. Tsulukiani has said ‘tens of millions’ will be spent on the reconstruction project, but many museum employees remain sceptical. ‘The essential part is that the process must be open, must be transparent,’ says Eka Kiknadze, the former manager of the museum, who was demoted to laboratory assistant by the new administration in late July. ‘The process must be led by professionals.’

William Dunbar lives in Tbilisi.

Georgia’s greatest museum has been saved from demolition, apparently – but for how long?

The building now home to the Shalva Amiranashvili Museum of Fine Arts, Tbilisi, shown in a 19th-century photo. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Share

Braving the scorching heat of the Georgian summer, on 4 August an unlikely crowd of bespectacled academics, young activists and assorted art lovers assembled in front of the Shalva Amiranashvili Museum of Fine Arts, Tbilisi, to protest about the threats that have emerged to Georgia’s most significant museum. The 1,000-strong crowd stood beneath the building’s massive pediment, releasing black smoke, making speeches and signing petitions calling for the preservation of both the building itself and its priceless collection of more than 139,000 objects.

The Art Museum, as it is known throughout the city, is literally a treasure house. It boasts the so-called Golden Fund, a repository of Christian art from the Golden Age of medieval Georgia from the 11th to 13th centuries: solid gold repoussé chalices, processional crosses, cloisonné enamels and scores of exquisite icons that have departed from the stiff formalism of Byzantium for a devotional art that feels expressive and alive. As if that wasn’t enough, the museum encompasses a superb collection of Islamic arts, including the most extensive collection of Qajar portraiture in the world; and the crown jewels of Georgian modern art, the work of the self-taught Georgian master Niko Pirosmani and his contemporaries.

Inside the Shalva Amiranashvili Museum of Fine Arts, Tbilisi (photo published in the Caryatid report of July 2021)

Inside the Shalva Amiranashvili Museum of Fine Arts, Tbilisi (photo published in the Caryatid report of July 2021)

Sadly, most of these exhibits have either been closed to the public or housed elsewhere for more than a decade – the Pirosmanis at the National Gallery of Georgia, for instance – as the museum’s building, a vast neoclassical edifice from 1835, has been allowed to decay. The Golden Fund remained open until 2019: housed in an increasingly dingy basement and patrolled by unreceptive museum guides of a type that will be familiar to any visitor to the Hermitage in the 1980s. A gradual decanting of the exhibits was meant to be followed by a comprehensive renovation of the building, for which for many years a plan has been in place, co-authored by specialists from the Smithsonian and elsewhere.

The fate of this plan, and of the museum itself, was thrown into doubt on 20 July, when the institution’s new director, Nikoloz Akhalbedashvili, called a meeting of the senior curatorial staff, collection managers and gallery attendants – more than 20 people were present – and made a devastating announcement. ‘He said that we must start the evacuation of all the objects,’ says Nino Khundadze, curator of modern and contemporary art, and keeper of the Pirosmanis.

‘He said he didn’t know where the objects should be taken, but that we must start the evacuation immediately and that it must be done very quickly,’ the urgency due to the parlous state of the museum’s building. The entire collection needed to be evacuated within six months, Akhalbedashvili told the meeting – an unfeasibly brief window for such a complex operation.

‘We asked what would happen with this building,’ Khundadze says. ‘And he said it is not the museum’s building any more. He said reconstruction of this building would be unprofitable, that we must give it to the ministry of economy – and what they do next we have no idea about.’ (Georgia’s ministry of economy and sustainable development is the body tasked with selling off state property).

Akhalbedashvili, a lawyer with no experience in museum studies, was appointed directly by Georgia’s new minister of culture, Tea Tsulukiani, in May this year. Tsulukiani, who also has no experience in arts and culture, is known for her hardline stance and fierce loyalty to billionaire oligarch Bidzina Ivanishvili, the country’s former prime minister (and its richest man), and the owner of a vast new glass and steel complex next door to the museum. Their connection has prompted many to speculate on the eventual plans for the museum site.

As news from the meeting leaked to opposition-minded media, Tsulukiani stepped in, calling the reports fake news, and castigating the museum administration as being responsible for the poor condition of the museum building. Ominously, her statement referred to a document prepared by a hitherto unheard-of company, Caryatid, that had provided the ministry with ‘expert analysis’ on the state of the building. The report recommended that large parts of the building would have to be destroyed, as renovating them would not be ‘commercially viable’.

Archive photograph of Tbilisi, showing (bottom left) the building later home to the Shalva Amiranashvili Museum of Fine Arts

Tbilisi has seen vast numbers of new developments in the last 10 years, with dozens of neoclassical and art nouveau treasures being lost to the wrecking ball, but the threat to museum is of a different category. It is among the oldest secular buildings in Georgia, and one of the first works of neoclassicism in the Caucasus. It is also historically significant, as the location of the Orthodox seminary in which Joseph Stalin (né Ioseb Jugashvili) was introduced to Marxism (he was subsequently expelled). It became a museum in 1953, the year of Stalin’s death, and since then has taken on a role that – by way of international comparison – combines the functions of the National Gallery and V&A in one building. News of its potential demolition was greeted with horror.

The public outcry appears to have had an effect. Speaking on 3 August, Tsulukiani denied there had ever been a plan to destroy any part of the building. Directly contradicting what her appointee Akhalbedashvili had told museum staff at the meeting on 20 July, she said the museum and all its exhibits would move back into the building once renovation was complete.

In spite of this apparent victory, the museum community in Georgia has little faith in its minister of culture. The ministry still appears determined to remove the collection in the next six months, a plan dubbed ‘unrealistic and unworkable’ by the Georgian chapter of the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS), the Georgian chapter of the International Council of Museums (ICOM), and the Georgian National Committee of the Blue Shield. Tsulukiani has said ‘tens of millions’ will be spent on the reconstruction project, but many museum employees remain sceptical. ‘The essential part is that the process must be open, must be transparent,’ says Eka Kiknadze, the former manager of the museum, who was demoted to laboratory assistant by the new administration in late July. ‘The process must be led by professionals.’

William Dunbar lives in Tbilisi.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

Share

Recommended for you

The jobbing artist who became Georgia’s national painter – thanks to his eye for a feast

Niko Pirosmani’s paintings are a testament to Georgian conviviality – although he didn’t always have a place at the table

Sheer delight – at the State Silk Museum in Tbilisi

The world’s most significant collection of silkworm cocoons, and many other marvels of sericulture, can be found in the capital of Georgia

Not even Stalin could snuff out the legacy of early Soviet photography and film

The Jewish Museum’s exhibition reveals the importance of formal innovation to freedom of expression