At its unveiling in 1897, Augustus Saint-Gaudens’ bas-relief memorial to Colonel Robert Gould Shaw and the 54th Massachusetts Infantry was hailed by reviewers as one of the most significant works of plastic art ever to have been produced in the United States. The sculpture commemorated the services and sacrifices rendered by one of the first African American regiments to fight for the Union during the American Civil War.

Located in Boston, home of the anti-slavery movement, it was celebrated not only for its artistic integrity but for its groundbreaking intricacy and racial accuracy in representing the black soldier. Departing from the postbellum sculptural tradition of the kneeling slave, Saint-Gaudens’ work emphasised the loyalty and selflessness of the 54th’s soldiers alongside the strength and leadership of their white Colonel in a piece which suggested social and racial cohesion at a time of proliferating segregation and violence.

Shaw Memorial (1900), Augustus Saint-Gaudens, U.S. Department of the Interior, on long-term loan to the National Gallery of Art

In a speech given at the sculpture’s dedication ceremony on Boston Common, William James saw in the figures a united movement onward, ‘a single resolution kindled in their eyes, and animating their otherwise so different frames’. The sculpture hasn’t always elicited such optimistic readings, and yet, as Tell It With Pride makes evident, it has had an enduring impact on the social, cultural and memorial practices of black and white American communities alike.

Produced to accompany a new exhibition that celebrates the sculpture and its afterlives, Tell It With Pride traces a detailed, illustrated history and legacy of the 54th Massachusetts’ renowned attack on Fort Wagner in July 1863. While the familiar stories of the regiment’s formation and wartime service, as well as of Saint-Gaudens’ lengthy creative process are covered, the book’s four essays approach the sculpture from fresh perspectives which examine the relationships between the sculpture and other artistic media from the late 19th century to the present day, and bring new life to the long-running commentary surrounding the work.

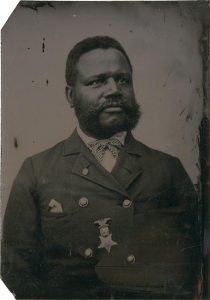

Private Charles A. Smith (c. 1880), unknown photographer, Courtesy of the Massachusetts Historical Society

Sarah Greenough’s opening chapter provides a compelling account of how and why the regiment’s soldiers, command, and supporters went about acquiring photographic images of themselves. Extensive illustrations are attended by Greenough’s perceptive close readings, which expose the complex political and racial tensions visible in some of the first photographs of African American men, and unpick the corporeal and material symbolism cultivated by a growing set of self-conscious celebrities.

Elsewhere, Nancy K. Anderson offers insight into other 19th-century artistic representations of Shaw, while Renée Ater describes the inspiration which Ed Hamilton’s 1998 Spirit of Freedom monument to African American servicemen and their families takes, practically and symbolically, from Saint-Gaudens’ project.

Possibly the strongest chapter of the collection is Lindsay Harris’s meditation on the place of the 54th and Saint-Gaudens’ sculpture in 20th-century art. Here, Harris surveys the ways in which the deeds of the 54th took on iconographic status for generations of black Americans seeking to define themselves and establish their citizenship in the years following the abolition of slavery. The chapter charts the use of images of the Shaw memorial in the home of the progressive ‘New Negro’, through the incorporation of 54th imagery into Carlos Lopez’s 1943 mural for the Recorder of Deeds building in Washington, D.C., and in Lincoln Kirstein’s 1973 photographic elegy to the memorial, Lay This Laurel.

Dealing sensitively with the changing significance of the 54th to the generations who lived through the upheaval of the Civil Rights years, Harris is the only author thoroughly to address the sculpture’s failings, the names of the African American soldiers it omits, and the acts of national forgetting which hinder a more holistic understanding of African American participation in America’s wars. Indeed, Tell It With Pride attempts to redress some of these failings remotely in its inclusion of an exhaustive roster listing the names of all known members of the 54th Regiment. Yet Harris leaves us with the unsettling feeling that the 54th’s work remains incomplete.

Where Nancy K. Anderson powerfully demonstrates how the Saint-Gaudens memorial has the power to remind an American veteran, blinded in Afghanistan, why he fought for his country, Harris makes it clear that some wartime histories go unrepresented, and that the march of progress has some way to go.

The exhibition ‘Tell it with Pride’ is at the National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C. until 20 January 2014, and at the Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston MA from 23 February–May 26 2014.

Tell It With Pride: The 54th Massachusetts Regiment and Augustus Saint-Gaudens’ Shaw Memorial, Sarah Greenough and Nancy K. Anderson with Lindsay Harris and Renée Ater (National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C. in association with Yale University Press).

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home