The British Museum’s current exhibition, about Stonehenge, features a display of sandstones recently unearthed on Salisbury Plain. Roughly rounded, these ‘hammerstones’ were used to shape the gigantic sarsens that form Stonehenge’s distinctive arrangement of uprights and capping lintels. This process would have left the air thick with dust – archaeologists found some 6,500 stone flakes in a single 5 metre by 5 metre trench – not to mention the constant clacking of stone on unyielding stone. It would have been arduously long: each of the blocks was intended to function with its fellows, held in their trilithon arrangement through what look like mortise and tenon joints. They had been quarried some 20 miles north, and probably arrived on a train of sledges, joining an existing arrangement of horseshoe-shaped bluestones whose own journey, from the Preseli Mountains, in west Wales, would have taken between 40 and 60 days and must still have been alive in oral tradition.

‘The World of Stonehenge’ underlines the fact that the construction of this ancient monument was not a standalone architectural project, but an evolving community effort, unfolding over 1,500 years and involving some 100 generations. The processes that went into it, and particularly those original journeys, must in themselves have been part of its cultural significance. Over the centuries, Stonehenge continued to prompt new kinds of travel and re-examination. Two chalk plaques buried nearby, featuring grooved motifs reminiscent of the trilithons, were probably offerings from Neolithic pilgrims from as far afield as Orkney or Ireland. In 1820, the same trilithons were visited by John Constable, whose watercolour of 1836 shows the great stones against a restless sky, their solid permanence in contrast to the evanescent double rainbow above, and the meandering 19th-century tourists below.

A Pictish warrior holding a human head, drawn by John White in 1585–93. © The Trustees of the British Museum

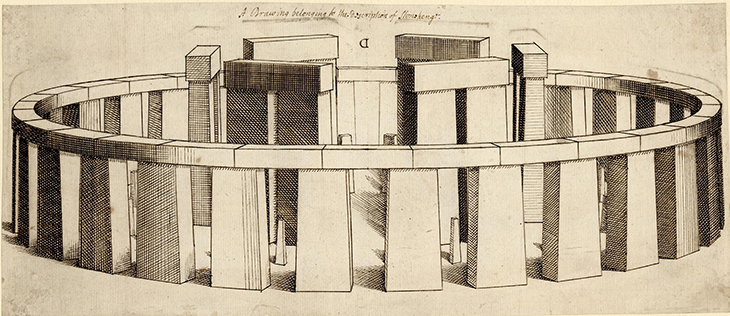

In the 17th and 18th centuries, ideas about the people who made Stonehenge were inflected by imperial exploration and the ‘discovery’ of Native Americans (in 1612) and of Pacific Islanders (in 1788), both widely seen as ‘children of nature’. John White’s drawings of Britons and Picts, published in John Speed’s Historie of Great Britaine (1611), are elaborately woad-covered versions of the native Virginians he drew during Raleigh’s expedition to North America in 1585. However, Inigo Jones was convinced Stonehenge must be a colonist’s construction. Writing in 1655, he described it as a Roman temple in the austere Tuscan order, sacred to Caelus, god of the heavens. His imaginative reconstruction of the monument’s original plan – based more on Vitruvius than Stonehenge – conceived it as two rings of concentric circles, with three symmetrical gaps. This remained the site’s major visual record until the fieldwork of the rival antiquarians William Stukeley – a former doctor and, subsequently, ordained vicar – and the architect and theorist John Wood, in the 1740s. Wood’s survey, published in 1747, is accurate in many cases up to a quarter of an inch, and remains useful today.

Preliminary drawing for an engraving in ‘The most Notable Antiquity of Great Britain, Vulgarly called Stone-Heng on Salisbury Plain, Restored by Inigo Jones Esquire‘ (1655) by John Webb. © The Trustees of the British Museum

Both Wood and Stukeley were drawn to Stonehenge’s distinctive circular form. Stukeley argued that the druids who built it had been colonists from Phoenicia. Nonetheless, they were a type of ‘noble savage’: having (somehow) received the divine truth of the Trinity, they were, Stukeley argued, essentially proto-Christian. As ‘the metropolitan church of the chief Druid of Britain’, the circle of Stonehenge therefore stood for ‘the infinity of nature in the Deity’ – and Stukeley made his own tribute to it in the apple orchard at his home in Grantham, which he converted into a series of pyramidal topiaries ‘in imitation of the inner circles at Stonehenge’, reflecting his theory that the origins of all druidic architecture lay in trees.

Wood, meanwhile, found the key to the monument at his birthplace, Bath. Convinced that ‘Bladud’, the town’s legendary founder, had been a Hyperborean priest of Apollo and a colleague of Pythagoras, Wood proposed that Bath was the druids’ metropolitan seat and Stonehenge one of four constituent colleges of their university. This ultimately informed his plan to redevelop his contemporary town along druidic lines. The results, including Queen Square, the North and South Parades and the Royal Crescent, are today synonymous with Georgian Bath, though in the face of contemporary opposition many had to be executed in fields outside the city walls. The immense stone circle of Wood’s monumental Circus (1754–68) is in the Neo-Palladian idiom, but lacks any classical precedent – with the solitary exception of the ‘Temple to Caelus’ as drawn up by Inigo Jones on Salisbury Plain, with which it shares its three symmetrical gaps.

In the 21st century’s first major re-examination of Stonehenge, the British Museum presents the world around it as one of international trade networks, increasing individualism – quashing the trend for collective burials – and dependence on the earth’s natural resources. Notwithstanding its focus on scientific research, ‘The World of Stonehenge’ underlines our tendency to discover our own preoccupations on Salisbury Plain.

‘The World of Stonehenge’ is at the British Museum, London, until 17 July.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home