If there is anything common across Indian painting’s broad reach – from abstract ideas depicted in bright flat colour to sophisticated court scenes of emperors and their nobles – it is rasa, a Sanskrit word whose meaning is central to Indian art, and which might be translated as ‘tasting the essence’, or ‘yielding delight’. And if there is anyone who can explain such concepts, opening up the world of Indian painting to a much wider audience, it is the art historian Professor Brijinder Nath Goswamy.

Born in the pre-independence Punjab area of northern India, Goswamy abandoned his civil service job in 1958, aged just 25, to devote himself to studying Indian art. Almost six decades later, his publications include the landmark catalogue he edited with Milo Beach and Eberhard Fischer to accompany the 2011 show ‘Masters of Indian Painting 1100–1900’, held in Zurich and New York. Now, in The Spirit of Indian Painting, he marries erudition with an acute eye and clear prose to produce an immensely readable book – one that could just as well be titled ‘How to enjoy Indian painting’.

Goswamy states that his aim is ‘not to present yet another history of Indian painting, but to bring readers/viewers into close contact with each work, and to make them feel the texture of its form and thought, to taste its essence or rasa’. He introduces the subtle colours of a lion’s coat in a Mughal hunting scene; shows how an artist draws us into the heart of a great battle between gods and demons; and points out how a portrait of the tolerant Sultan Ibrahim Adil Shah II of Bijapur reveals how he saw himself as both a devout Muslim and a Hindu.

It might be tempting to skip Goswamy’s long preamble essay, ‘A Layered World’, enjoying instead his rigorous selection of 101 great paintings, each given a full-page illustration opposite his thoughtful commentary. This would be a mistake. For in this essay he addresses why these paintings – usually small and made on paper using gouache paints – were made as they were, and how we might best understand them today.

Goswamy discusses what the paintings were illustrating, what emotions they were intended to stir in the viewer, as well as the aim of a portrait and the relationship of patron and artist. He also points out the job of landscape to echo human emotion, vital details that add so much to the overall meaning, and the essential presence of human action. Even poems about the months of the year are given their visual equivalent through lovers meeting, sharing, being separated. Spring is expressed through an entwined couple sitting on a swing suspended from a fruiting tree in a blossoming stage-set garden. Indeed, the word rasa was originally used to describe Sanskrit theatre, where actors, costumes, scenery and props all contributed to its success.

The most rewarding passages discuss the distinctly Indian views on time, space and colour. Goswamy writes of time being cyclical as well as infinite, and thus to some extent elastic. He considers how space can expand or shrink, and is manipulated by the artist according to need; a painting can have various viewpoints rather than follow familiar Western ideas on perspective. He writes about the dazzling colour that saturates paintings. In a dramatic picture of the god Indra dancing, a whole landscape is reduced to flat, hot, erotic vermilion as powerful as that in a Rothko canvas while, elsewhere, wooded mountains are painted magenta and flame-orange. Together, these generate the climactic effect of rasa for the viewer. This moment is called ‘the churning of the heart’, when the reader can attain the appropriate emotional state to respond in full to the painting’s bhava, or mood.

In order to experience this, Goswamy suggests, a painting should be held in the hand and considered carefully in its full context. Hurrying past an Indian painting hung on the living-room wall was not what the patron or artist had in mind; paintings were kept wrapped up away from damaging light and brought out to enjoy when their owner made specific time for contemplating them. The closest a reader can probably get to such quiet personal contemplation is to look at Goswamy’s selection. Broadly, it ranges from Jain and Hindu to Mughal, Deccan and Company School, with much mingling of styles. It is arranged in four loose themes: Visions, Observation, Passion, and Contemplation.

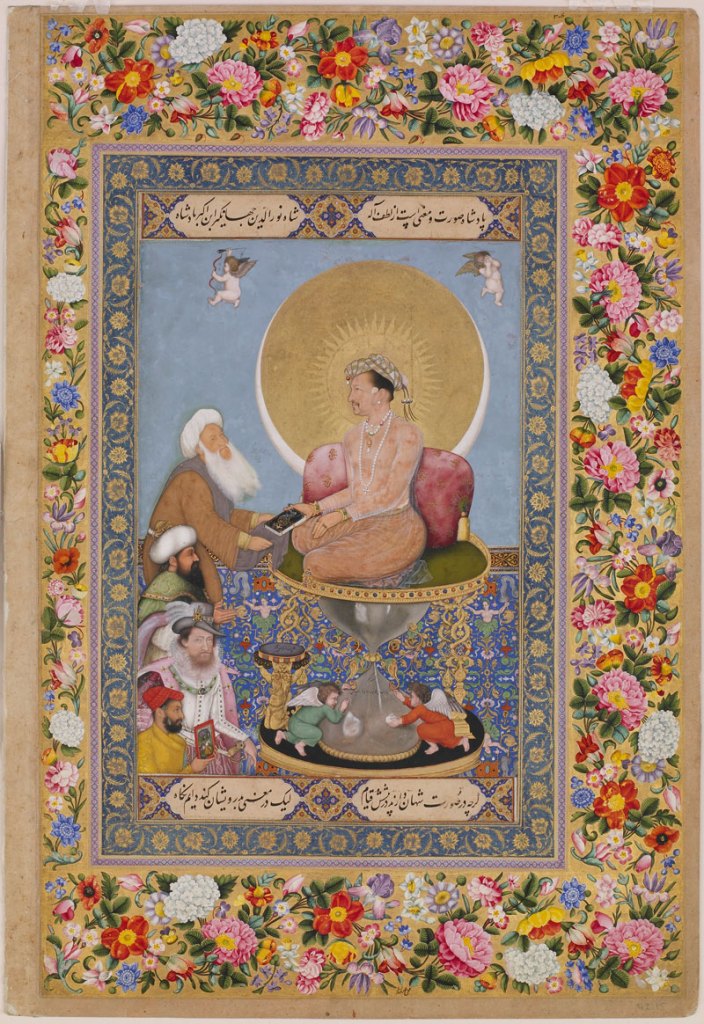

Jahangir Preferring a Sufi Shaikh to Kings , from the St Petersburg Album, (1615–18), Bichitr. Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institute, Washington D.C.

The Passion group has a stunning page from a 16th-century manuscript of the popular 11th-century love lament Chaurapanchasika, made near Agra. It illustrates the verse (written along the top) recounting the moment when a lover leaves his mistress and remembers her beauty as ‘fragile and fawn-eyed’, but ‘moving like a wild goose’. As Goswamy observes, nothing in the picture ‘obeys ordinary laws’ – flowers are suspended in mid-air, daytime sky is star-spangled, water cisterns are spliced open but no water runs out, bumblebees fly around the fiery mistress’s head, the colours of house, landscape and figure are vermilion, moss green and saffron. Yet ‘all blends into a harmonious whole’. In contrast to this bold abstraction, the Observation section includes star Mughal artist Bichitr’s fantasy assemblage of real figures – yet even he gives the work a spiritual focus. His heavily bejewelled patron, Emperor Jahangir, receives the powerful Sultan of Turkey, James I of England and, in the corner, the artist himself. Yet no one is more honoured than humble Sufi, Sheikh Hussain, descendant of the Chishti saint at whose shrine Jahangir’s father worshipped in the hope of having a son. That son now gazes intently at the Sufi, not at fellow kings.

Goswamy suggests that by fully concentrating on a great painting, ‘a person would involuntarily experience a heightened state’ and arrive at ‘romaharsha’, a sensation of sudden pleasure that literally means ‘the hair on my body has become happy’. This is rasa taken to its limit.

The Spirit of Indian Painting: Close Encounters with 101 Great Works 1100–1900, by B.N. Goswamy, is published by Thames & Hudson.

From the June issue of Apollo: preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home