As a university student in London in the late 1960s I longed to live in Habitat-furnished surroundings, rather than a cramped shared flat above a shoe shop, full of ugly utility furniture and shiny synthetic fabrics. Once I had the chance, I was off to Habitat. The sofa – or bed for visitors – was fiendishly uncomfortable: two blocks of foam with detachable back and sides, wrapped in sandy-coloured elephant cord. Then came the red- and green-stained bentwood chairs, with similar elephant cord fabric on the detachable seats. I still have several. This was exactly the kind of basic furniture I and my peers wanted, and could just about afford. And it wasn’t other people’s hand-me-downs. The late Terence Conran’s genius was, as has been said elsewhere, to be an editor and entrepreneur when it came to style, with ventures such as Habitat reflecting his own preferences and suiting the aspirations of his customers. He seized the attention of a generation and, remarkably, held it.

Terence Conran’s The House Book was published by Mitchell Beazley in 1974. Even if we did not resemble or behave like the people in his pages, we could admire their assurance. This and the succession of lavishly designed volumes that followed were soon being published under the imprint Conran Octopus, co-founded by Conran and Paul Hamlyn in the 1980s. These included the New House Book of 1985. I wrote a section titled ‘architectural character’, a completely anodyne guide to conservative restoration, pitched to an audience in New England or England, Sydney or Montreal. Conran’s market was diverse in terms of nationality, but firmly young, metropolitan and middle-class.

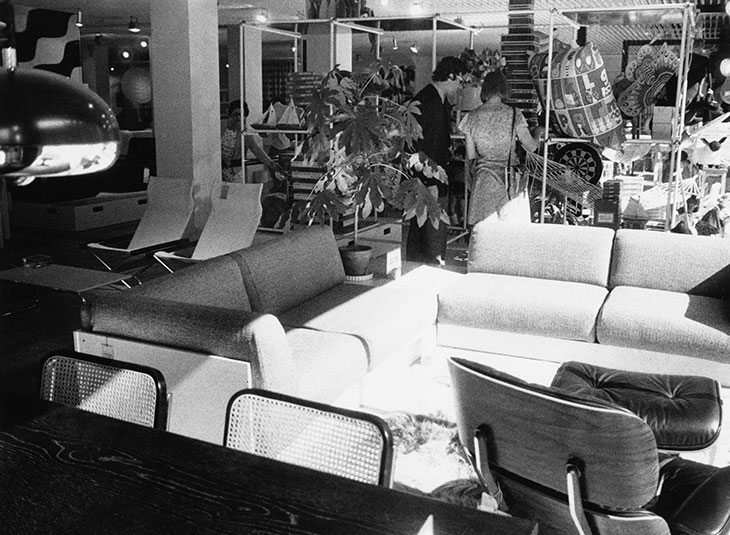

Customers in a Habitat furniture store, 1973. Photo: Evening Standard/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

The speed at which Conran grasped new ventures and expanded his existing ones suggested a restless appetite and – as the obituaries of recent days make clear – a driving, challenging personality. The culmination of all his initiatives, which had begun with the opening of the first Habitat store on the Fulham Road in 1964, was to be an internationally recognised design museum in the capital, funded and controlled by his own foundation. This began with the Boilerhouse Project, an underground exhibition space for industrial design at the V&A that opened in January 1982 while Roy Strong was still the museum’s director. Conran Roche, the firm Terence Conran and Fred Roche had set up in 1980, converted the site and the writer and critic Stephen Bayley was appointed its founding director. But a major government-sponsored museum of the decorative arts – itself just moving towards independence – did not easily accommodate the world of commercial product design. After 23 exhibitions it closed.

Inside Bibendum restaurant at Michelin House, Fulham Road, photographed c. 1993. Photo: Wikipedia/DRD (CC BY-SA 3.0)

The new Design Museum opened in a converted banana warehouse at Shad Thames in 1989 with Bayley again as its first director. More than anyone, perhaps, Bayley understood the vision, courage and sheer obduracy of the man who had made the museum his mission. (Subsequent directors did not always find their own aspirations for the museum so well aligned with those of its founder.) Conran Roche were the architects once more, and the cost was given as £7 million. Conran was involved in every element of the project, and a restaurant, named Blueprint Café, was just one of a growing stable of elegant establishments in his gastronomic empire – though none was more enticing and stylish than Bibendum, the old Michelin depot on the Fulham Road.

Conran envisaged the museum as the cultural lynchpin of a major refurbishment of Shad Thames, driving out (to my great sadness) the enveloping essence of cardamom and cumin from a warehouse district that had been more Cochin than Bermondsey. Nearby, Conran also took on as his company HQ the exquisite Michael Hopkins-designed building, backing on to the water, that had been commissioned as a showroom and offices by the cutlery designer David Mellor. The contrasts in approach between these two key figures in late 20th-century British design are telling: Mellor, a craftsman and specialist; Conran, an entrepreneur and generalist.

The Design Museum at its Kensington site in 2016. Photo: © Luke Hayes

In what was to be final act of his career, Terence Conran drove forward yet another iteration of the Design Museum, this time housed in the listed Commonwealth Institute in Kensington. At the press opening of John Pawson’s redeveloped building in 2016, Conran sat centre stage alongside Deyan Sudjic and Alice Black, the museum’s then co-directors (Tim Marlow took over this January). I sensed that here, hubris – displayed in the stupendous sums of money spent transforming an unsuitable building – had overcome good sense. Now I perch on my Habitat bentwood chair and celebrate Terence Conran for everything he achieved for us all.

Enterprising spirit – how Terence Conran built his design empire

Terence Conran at the opening of his exhibition ‘Terence Conran: The Way We Live Now’ at the Design Museum, London, 2011. Photo: Carl Court/AFP via Getty Images

Share

As a university student in London in the late 1960s I longed to live in Habitat-furnished surroundings, rather than a cramped shared flat above a shoe shop, full of ugly utility furniture and shiny synthetic fabrics. Once I had the chance, I was off to Habitat. The sofa – or bed for visitors – was fiendishly uncomfortable: two blocks of foam with detachable back and sides, wrapped in sandy-coloured elephant cord. Then came the red- and green-stained bentwood chairs, with similar elephant cord fabric on the detachable seats. I still have several. This was exactly the kind of basic furniture I and my peers wanted, and could just about afford. And it wasn’t other people’s hand-me-downs. The late Terence Conran’s genius was, as has been said elsewhere, to be an editor and entrepreneur when it came to style, with ventures such as Habitat reflecting his own preferences and suiting the aspirations of his customers. He seized the attention of a generation and, remarkably, held it.

Terence Conran’s The House Book was published by Mitchell Beazley in 1974. Even if we did not resemble or behave like the people in his pages, we could admire their assurance. This and the succession of lavishly designed volumes that followed were soon being published under the imprint Conran Octopus, co-founded by Conran and Paul Hamlyn in the 1980s. These included the New House Book of 1985. I wrote a section titled ‘architectural character’, a completely anodyne guide to conservative restoration, pitched to an audience in New England or England, Sydney or Montreal. Conran’s market was diverse in terms of nationality, but firmly young, metropolitan and middle-class.

Customers in a Habitat furniture store, 1973. Photo: Evening Standard/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

The speed at which Conran grasped new ventures and expanded his existing ones suggested a restless appetite and – as the obituaries of recent days make clear – a driving, challenging personality. The culmination of all his initiatives, which had begun with the opening of the first Habitat store on the Fulham Road in 1964, was to be an internationally recognised design museum in the capital, funded and controlled by his own foundation. This began with the Boilerhouse Project, an underground exhibition space for industrial design at the V&A that opened in January 1982 while Roy Strong was still the museum’s director. Conran Roche, the firm Terence Conran and Fred Roche had set up in 1980, converted the site and the writer and critic Stephen Bayley was appointed its founding director. But a major government-sponsored museum of the decorative arts – itself just moving towards independence – did not easily accommodate the world of commercial product design. After 23 exhibitions it closed.

Inside Bibendum restaurant at Michelin House, Fulham Road, photographed c. 1993. Photo: Wikipedia/DRD (CC BY-SA 3.0)

The new Design Museum opened in a converted banana warehouse at Shad Thames in 1989 with Bayley again as its first director. More than anyone, perhaps, Bayley understood the vision, courage and sheer obduracy of the man who had made the museum his mission. (Subsequent directors did not always find their own aspirations for the museum so well aligned with those of its founder.) Conran Roche were the architects once more, and the cost was given as £7 million. Conran was involved in every element of the project, and a restaurant, named Blueprint Café, was just one of a growing stable of elegant establishments in his gastronomic empire – though none was more enticing and stylish than Bibendum, the old Michelin depot on the Fulham Road.

Conran envisaged the museum as the cultural lynchpin of a major refurbishment of Shad Thames, driving out (to my great sadness) the enveloping essence of cardamom and cumin from a warehouse district that had been more Cochin than Bermondsey. Nearby, Conran also took on as his company HQ the exquisite Michael Hopkins-designed building, backing on to the water, that had been commissioned as a showroom and offices by the cutlery designer David Mellor. The contrasts in approach between these two key figures in late 20th-century British design are telling: Mellor, a craftsman and specialist; Conran, an entrepreneur and generalist.

The Design Museum at its Kensington site in 2016. Photo: © Luke Hayes

In what was to be final act of his career, Terence Conran drove forward yet another iteration of the Design Museum, this time housed in the listed Commonwealth Institute in Kensington. At the press opening of John Pawson’s redeveloped building in 2016, Conran sat centre stage alongside Deyan Sudjic and Alice Black, the museum’s then co-directors (Tim Marlow took over this January). I sensed that here, hubris – displayed in the stupendous sums of money spent transforming an unsuitable building – had overcome good sense. Now I perch on my Habitat bentwood chair and celebrate Terence Conran for everything he achieved for us all.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

Share

Recommended for you

‘An amplitude of personal charm’ – Desmond Guinness (1931–2020)

Desmond Guinness fought against the odds, and often against public opinion, to save Irish Georgian houses – and the nation will be forever in his debt

The Design Museum takes to the dance floor

An exhibition dedicated to the music of the future may be too respectful of its past

Mid-Century Modern: Art & Design from Conran to Quant

How Swinging London became the centre of a revolution in style – an exhibition at Dovecot Studios