No one can predict what may happen at an auction, especially in China. On 26 November, Christie’s Hong Kong will offer the 11th-century ink-on-paper painting Wood and Rock. To Western eyes, the pre-sale estimate of ‘upwards of HK$400m’ (£40m) may seem a mighty amount for a work of art so small – 26 by 50 centimetres – and unassuming. Yet this Song dynasty-era study is hailed as an exceedingly rare work, and the only one remaining in private hands, by Su Shi (1037–1101), one of Chinese history’s most renowned and influential figures.

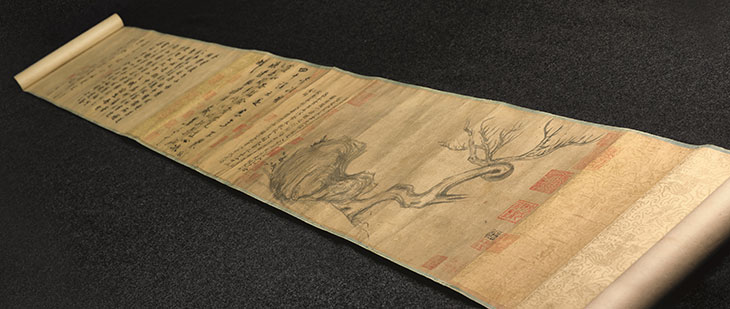

Wood and Rock is set into an extended handscroll bearing four colophons, or commentaries, including one by Su Shi’s contemporary, the pre-eminent calligrapher, poet and painter Mi Fu, and 41 collector’s seals. Now measuring more than five metres long, the scroll, according to the auction house, is ‘set to become one of the most important works in auction history’. What they really mean is one of the most expensive.

Su Shi was a polymath. One of the scholar-officials, or literati, who governed imperial China, he excelled as a poet, wide-ranging essayist, calligrapher and painter. He is also believed to have travelled to more places in China than anyone before him – not least due to various periods in exile. These years of adversity and poverty prompted many of his most admired poems and paintings. Fewer than a handful of the latter survive. Despite their apparent simplicity, they have been described as works of ‘silent poetry’, rich in metaphor. As Mi Fu wrote of Su’s gnarled trees and peculiar rocks, it is ‘almost as if they are the very vessel for his sorrow and melancholy’.

Wood and Rock (11th century), Su Shi. Courtesy Christie’s

This was a new kind of landscape painting, mediated through the mind of the artist and far removed from the meticulously crafted observations of nature found in court art. In painting as well as poetry, Su favoured directness, spontaneity and expressiveness. By borrowing the brushwork of the calligrapher’s art, he also appropriated its cultural authority. Su Shi and his contemporaries effectively transformed painting from an artisanal practice into a pursuit worthy of a gentleman-scholar and laid the foundations for literati painting. The complete scroll is more than a painting: it is a record of the cultural milieu in which this genius flourished and became revered.

In explaining the importance of Su Shi to an international audience, it is understandable that Christie’s experts have drawn analogies with that most famous of all Western polymaths – the archetypal Renaissance man, Leonardo da Vinci. To those in Asia where Su Shi is a household name, however, the analogy is useful in establishing a price frame for a work of supreme cultural importance. In 1994, the Leonardo manuscript of scientific writings known as the Codex Leicester was offered at Christie’s New York where it was bought by Bill Gates for $30.8m – around $50m today. Inevitably, the painting of Salvator Mundi has been much mentioned too, and that changed hands for $450m.

In terms of Chinese painting, the Six Dragons handscroll listed in a Qing imperial inventory as the work of Chen Rong (c. 1200–66) fetched almost $49m last year, again at Christie’s New York. At Poly International Auction Co. in Beijing, however, a 15 metre-long calligraphic handscroll by the Song master Huang Tingjian realised the equivalent of $63m in 2010, the record for any historic Chinese work of art sold at auction.

Like Six Dragons, which was deaccessioned by the Fujita Museum, Wood and Rock is also being consigned from Japan. In 1937 a dealer in Beijing, whose wife was from Japan, sold it to a Japanese collector named Abe Fujisarom. The scroll appears never to have been seen in public, and was previously only known by a black-and-white collotype print made in Japan shortly after its purchase. Given also that so little of the master’s work survives, how can we be sure that painting is indeed by Su Shi?

According to Malcolm McNeill, newly appointed Chinese paintings specialist at Christie’s in London, catalogues of the Qing imperial painting and calligraphy collections compiled in the 18th century form the lion’s share of extant documentation of provenance. Less survives of records of private collections – this painting passed down through the centuries in private hands. It was originally a gift from Su Shi to one Master Feng; subsequent provenance is outlined by the collector’s seals that date up to 1644, the period in which the scroll was probably mounted. McNeill continues: ‘The identification of the artist is founded on meticulous scholarship on the accompanying colophons [mentioning Su’s authorship], in particular the colophon by Su’s contemporary Mi Fu. These inscriptions have been the subject of assiduous research by leading scholars from both within and without China […]. No one who has seen the scroll has been in any doubt whatsoever that it is authentic.’

Wood and Rock will lead the Christie’s Hong Kong Autumn Sale on 26 November.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home