Unseasonal downpours drench Reggio Emilia in July. The crowds in town for Fotografia Europea huddle under the city’s porticos, welcome shelter between venues. As I dash towards the Palazzo Magnani my eye is caught by a sculpture of Janus on its corner. His two heads – one young, one old – pull in opposite directions. The theme of the 12th edition of Fotografia Europea is memory, archive, and the future; this image of generational discord on the façade of its headquarters is a wry counterpoint to the story of untroubled heredity presented inside, where an exhibition shows the influence of Paul Strand and Cesare Zavattini’s neorealist photobook Un Paese. Shot in the nearby village of Luzzara in the early 1950s, these stark photographs are a reminder of how much Italy has changed in two generations.

I am in Reggio Emilia not for the photography festival, but to visit a building that had not even been commissioned when Strand came to town, but already enjoys a second life: the Max Mara factory, just outside the historic centre, which is now known as Collezione Maramotti and opened to the public in 2007. For 10 years, this frontrunner among Italy’s contemporary cultural foundations has had two faces – an art collection spanning 1945 to 2000, begun in the 1960s by Achille Maramotti, the founder of the womenswear company, and a contemporary art programme, including the biannual Max Mara Art Prize for Women. Two of the 10th anniversary exhibitions – Emma Hart’s ‘Mamma Mia!’ and Elisabetta Benassi’s ‘It starts with the firing’ – have an appropriate undercurrent of intergenerational angst.

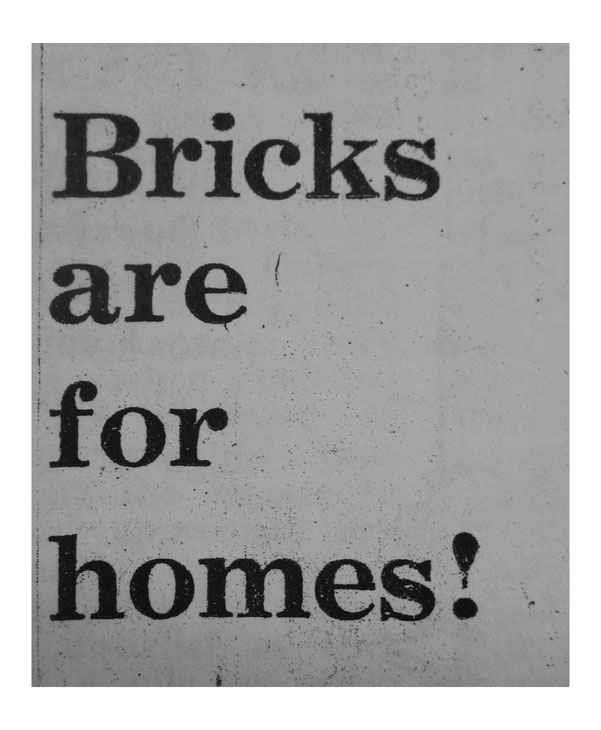

Newspaper cutting collected by Elisabetta Benassi for her exhibition ‘It starts with the firing’ at the Collezione Maramotti, 2017. Courtesy Elisabetta Benassi

Benassi’s exhibition (until 17 September) starts outside the gallery. Billboards around Reggio Emilia read ‘A brick is a brick is a brick’; ‘My wall is going cheap’; ‘Bricks are for homes!’. The headlines come from ‘the Bricks controversy’, after the Tate’s acquisition of Carl Andre’s Equivalent VIII in 1972. Benassi has mined the press clippings Andre assembled and donated to the Tate archive for her own site-specific commission. She courts the art outrage of another era for this location: installing an ironing machine, now automated to gently steam, and shredding Max Mara coat fabric to resemble Robert Morris felt. Benassi’s co-option of the headlines for her own brick structures, her neatly built wall traversed by oriental rugs, feels like an attempt to free it from the current moment of walls and boundaries, as well as to poke fun at masculine minimalism.

Benassi’s bricks are not equivalent to Andre’s. Each work uses a different kind of brick. The most compelling, Zeitnot, uses 5,000 bricks handmade in Hertfordshire by a 99-year old artisan. The structure is almost painterly in its gradation from ochre to aubergine. It is hard not to see it as a refuge, and these bricks as temporal and geographical migrants – as resonant with Italy’s contemporary immigration crisis as its post-war emigration to work in British brick factories.

Further down the Via Emilia, a British artist is in Faenza to make ceramics. Emma Hart is the sixth winner of the Max Mara Art Prize for Women, but the first to produce her work in Italy. The prize offers a six-month Italian residency to research a project to be exhibited at the Whitechapel Gallery, and then at the Collezione Maramotti. Hart’s project will also travel to the Fruitmarket Gallery in Edinburgh.

Hart’s journeys in Italy, undertaken with her partner and daughter, may appear disjointed: she researched the Milan Systems approach to family therapy at the Mara Selvini Palazzoli School in Milan, joined the contemporary art scene around Alighiero Boetti’s former studio in Todi, finally working with the ceramics at the Museo Carlo Zauli in Faenza. Hart found the connection on an excursion to the hill-town of Deruta, Umbria, known for its maiolica; for Hart, the repeating patterns of the ceramic decoration recalled the behavioural patterns of family relationships.

In the resulting work (at the Whitechapel Gallery, London, until 3 September), Hart presents large ceramic heads suspended from the ceiling at different heights, seemingly a family in dialogue. On closer inspection, these monochrome heads are upturned and oversized jugs. You can stand beneath, to see their vivid interior decoration of simply drawn and cleverly conceived psychological patterns of interaction. Green vines twist in cycles of jealousy. Speech bubbles become tears in unending narcissistic dialogues. Each head-jug contains a light bulb projecting on to the floor the form of a speech bubble, which is regularly disrupted by the shadow of rotating ceiling fans made of giant cutlery, acting at once as muting mouthfuls and whirling guillotines.

Installation view of Emma Hart’s ‘Mamma Mia’ exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery, London, 2017. Photo: Thierry Bal; © Whitechapel Gallery

The balance of playful and ominous is typical of Hart. She trained in silver-print photography, but turned to clay five years ago, a medium she finds comparable to film photography in its recording of movement and reliance on processing, but better suited to capturing trauma. The trip to Faenza was born of her love of clay, and the opportunity to work with master ceramicist Aida Bertozzi was liberating. Hart’s technical limitations in the medium had previously been part of her process, now she could focus on other things, particularly the insides of the heads, which were painted back in her Peckham studio.

Hart notes that throughout her travels in Italy she was meeting the sons of the founders of eponymous institutions, starting and ending with Collezione Maramotti. While not exclusive to Italy, family foundations are increasingly part of its cultural landscape, giving a distinct character to intergenerational artistic relations. Part of the optimistic buzz around Collezione Maramotti is that like Benassi’s bricks and Hart’s maiolica heads – and unlike the Palazzo Magnani Janus – this institution invites both retrospection and foresight.

From the September 2017 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home