The Endeavour passed the high chalk cliffs of Beachy Head at sunrise on 12 July 1771, on its return from Captain James Cook’s first voyage of exploration to the Pacific. The account of the voyage’s many discoveries of lands, fauna and peoples took Britain and the rest of Europe by storm, turning Cook and the naturalist Joseph Banks into overnight celebrities. The ship that had successfully taken them around the world for three years, meanwhile, was rapidly forgotten. The Endeavour had served at once as a mode of transport, a home, a floating laboratory and a quasi-prison during perilous weeks at sea, and it is not surprising that the surviving members of Cook’s crew were quick to make their way off her deck upon their return to Britain. Within a week she was taken away to Woolwich Dockyard where she was refitted as a marine transport. She spent the next three years sailing to and from the Falkland Islands before being decommissioned and sold by the Royal Navy in 1775. Then she vanished from the historical record for two hundred years, her ultimate fate unknown except for speculation and hearsay.

It wasn’t until 1999 that the Rhode Island Marine Archaeology Project (RIMAP), investigating the identity of 13 ships sunk in Newport Harbour in 1778, discovered that one of the ships, the Lord Sandwich, was in fact Cook’s Endeavour. It transpired that she had been renamed before being recommissioned into the Royal Navy in 1776 to serve as a transport ship in the American War of Independence. After transporting German mercenaries across the Atlantic and taking part in the capture of New York, the Endeavour was converted into a floating prison to hold American rebels. She was finally scuttled in shallow waters on 4 August 1778, along with other surplus vessels, to block the entrance of Newport Harbour to prevent its capture by the French fleet.

The team of marine archaeologists at RIMAP are now convinced that the Endeavour’s wreck forms part of a cluster of five ships that were sunk together. Four of these ships have already been located (and remote sensing data suggest that the fifth also survives somewhere in the murky waters of Newport Harbour) so in fact it is quite possible that she has already been found. Further excavations and the study of some of the ships’ artefacts should allow us to determine which ship is the Endeavour. It is particularly ironic that the first British ship to touch the coast of Australia, thus forming one of the foundations of Britain’s 19th-century empire, was sunk off the coast of Rhode Island, the first American state to disavow its loyalty to King George III.

The Endeavour was launched in 1764 (as the Earl of Pembroke) in Whitby, the North Yorkshire port from where James Cook first served as a merchant navy apprentice, and which today houses the excellent Captain Cook Memorial Museum. At 30 metres long, the Endeavour was a modest but sturdy ship with a square stern and a deep hold, made for carrying coal. She was purchased by the Royal Navy in 1768 and refitted for a voyage of exploration to observe the transit of Venus from Tahiti and to seek for Terra Australis, a hypothetical southern continent. Helmed by Cook, the expedition left Plymouth in August 1768 carrying 94 men, including sailors and marines but also a large group of civilians comprising botanists, astronomers and artists. The Endeavour headed south, around Cape Horn and into the uncharted Pacific.

In April 1769, nine months after her departure from Britain, the Endeavour reached Matavai Bay on the island of Tahiti. There, the crew spent three bountiful months, on an island that in the European imagination embodied the idea of the South Seas as an earthly paradise, free from the ills of civilisation. The Endeavour then sailed west across the Pacific and, with the help of Tupaia, a Tahitian navigator who had joined the crew, reached the coast of New Zealand in October. They were only the second European party ever to reach New Zealand (after the Dutch Abel Tasman in 1642) and spent half a year mapping out the entirety of its coastline.

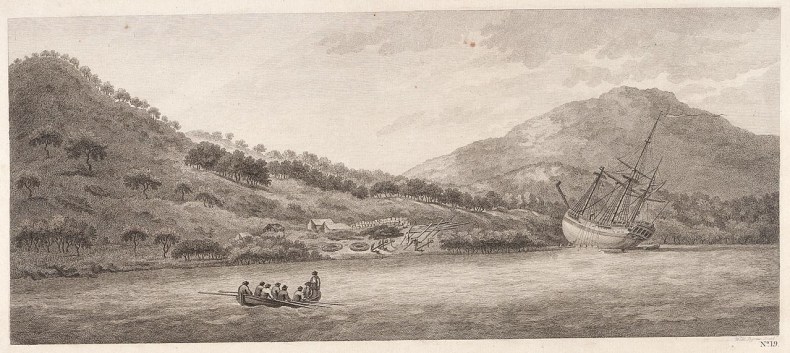

Cook then continued west, and recorded sighting the coast of Australia at 6am on Thursday 19 April 1770. A little more than a week later, the Endeavour anchored in Botany Bay. The bay was earmarked as a potential site for a British colonial settlement, and 18 years later the settlement of Sydney was established a few kilometres further north. But the news almost never reached Britain. On its way up the Australian coast, the Endeavour ran aground on the Great Barrier Reef and nearly sank. Seven weeks of repairs on a beach allowed for much botanical exploration and largely friendly encounters with Aboriginal Australians – encounters which, among many other fruitful exchanges, allowed ‘kangaroo’ to enter the English language. The Endeavour then sailed north through the Torres Strait, stopped in the East Indies, rounded the Cape of Good Hope and headed home along the west coast of Africa.

The voyage had precise scientific and political aims, but it was also unique for being the first time that a large party of scientists and artists were taken on board, with the sole aim to record and analyse the many plants, animals and peoples they would encounter. Cook’s voyage not only amassed a vast number of natural and ethnographic ‘specimens’, but thousands of pages filled with accounts of Polynesian customs. Some of these records were so thorough, that their authors might well be considered the very first ethnographers of the Pacific. The most remarkable of these proto-ethnographers was the young Joseph Banks. When questioned by alarmed members of his family about why, unlike his peers who complemented their education by touring the ancient ruins of Europe and the Mediterranean, he wished to sail into the uncharted Pacific with little hope of ever coming back, Banks reputedly replied that ‘every blockhead does that. My Grand Tour shall be one around the world.’ Banks never returned to the Pacific, but the example he set with his companions influenced many subsequent voyages and revolutionised the practice of science.

I have spent the last few days daydreaming about what traces of this extraordinary voyage we may find in the wreck of the Endeavour. Unfortunately, as the ship changed hands so many times after its return from the Pacific, the likely answer is not many. We could, however, still hope to see signs of the extensive repairs the Endeavour underwent after striking the Great Barrier Reef, testament to the grit and resilience of its crew.

The excavation of the Endeavour will probably prove far less exciting than that of the wrecks of la Boussole and l’Astrolabe, Jean-François de La Pérouse’s two ships, which were formally identified in 2005 off Vanikoro in the Solomon Islands, still filled with the remains of equipment from an extravagant expedition that was Louis XVI’s response to the Cook voyages. But the lumps of wood from the Endeavour’s hull still carry more significance. The sheer amount of coverage this discovery has received is testament to the enormous importance this unassuming, unremarkable little ship has taken on in the collective imagination. For some the Endeavour is a positive symbol of the foundation of Australia, for others, the first step towards the ruthless annihilation of the Australian continent’s Aboriginal peoples. While celebrating the Endeavour’s discovery, and through it Cook’s extraordinary achievements, we should also take a moment to reflect on the huge and lasting impact this small ship had on hundreds of thousands of lives in the South Seas.

The Endeavour won’t tell us anything new about Cook’s voyage, but that’s not the point

Share

The Endeavour passed the high chalk cliffs of Beachy Head at sunrise on 12 July 1771, on its return from Captain James Cook’s first voyage of exploration to the Pacific. The account of the voyage’s many discoveries of lands, fauna and peoples took Britain and the rest of Europe by storm, turning Cook and the naturalist Joseph Banks into overnight celebrities. The ship that had successfully taken them around the world for three years, meanwhile, was rapidly forgotten. The Endeavour had served at once as a mode of transport, a home, a floating laboratory and a quasi-prison during perilous weeks at sea, and it is not surprising that the surviving members of Cook’s crew were quick to make their way off her deck upon their return to Britain. Within a week she was taken away to Woolwich Dockyard where she was refitted as a marine transport. She spent the next three years sailing to and from the Falkland Islands before being decommissioned and sold by the Royal Navy in 1775. Then she vanished from the historical record for two hundred years, her ultimate fate unknown except for speculation and hearsay.

It wasn’t until 1999 that the Rhode Island Marine Archaeology Project (RIMAP), investigating the identity of 13 ships sunk in Newport Harbour in 1778, discovered that one of the ships, the Lord Sandwich, was in fact Cook’s Endeavour. It transpired that she had been renamed before being recommissioned into the Royal Navy in 1776 to serve as a transport ship in the American War of Independence. After transporting German mercenaries across the Atlantic and taking part in the capture of New York, the Endeavour was converted into a floating prison to hold American rebels. She was finally scuttled in shallow waters on 4 August 1778, along with other surplus vessels, to block the entrance of Newport Harbour to prevent its capture by the French fleet.

The team of marine archaeologists at RIMAP are now convinced that the Endeavour’s wreck forms part of a cluster of five ships that were sunk together. Four of these ships have already been located (and remote sensing data suggest that the fifth also survives somewhere in the murky waters of Newport Harbour) so in fact it is quite possible that she has already been found. Further excavations and the study of some of the ships’ artefacts should allow us to determine which ship is the Endeavour. It is particularly ironic that the first British ship to touch the coast of Australia, thus forming one of the foundations of Britain’s 19th-century empire, was sunk off the coast of Rhode Island, the first American state to disavow its loyalty to King George III.

The Endeavour was launched in 1764 (as the Earl of Pembroke) in Whitby, the North Yorkshire port from where James Cook first served as a merchant navy apprentice, and which today houses the excellent Captain Cook Memorial Museum. At 30 metres long, the Endeavour was a modest but sturdy ship with a square stern and a deep hold, made for carrying coal. She was purchased by the Royal Navy in 1768 and refitted for a voyage of exploration to observe the transit of Venus from Tahiti and to seek for Terra Australis, a hypothetical southern continent. Helmed by Cook, the expedition left Plymouth in August 1768 carrying 94 men, including sailors and marines but also a large group of civilians comprising botanists, astronomers and artists. The Endeavour headed south, around Cape Horn and into the uncharted Pacific.

In April 1769, nine months after her departure from Britain, the Endeavour reached Matavai Bay on the island of Tahiti. There, the crew spent three bountiful months, on an island that in the European imagination embodied the idea of the South Seas as an earthly paradise, free from the ills of civilisation. The Endeavour then sailed west across the Pacific and, with the help of Tupaia, a Tahitian navigator who had joined the crew, reached the coast of New Zealand in October. They were only the second European party ever to reach New Zealand (after the Dutch Abel Tasman in 1642) and spent half a year mapping out the entirety of its coastline.

Cook then continued west, and recorded sighting the coast of Australia at 6am on Thursday 19 April 1770. A little more than a week later, the Endeavour anchored in Botany Bay. The bay was earmarked as a potential site for a British colonial settlement, and 18 years later the settlement of Sydney was established a few kilometres further north. But the news almost never reached Britain. On its way up the Australian coast, the Endeavour ran aground on the Great Barrier Reef and nearly sank. Seven weeks of repairs on a beach allowed for much botanical exploration and largely friendly encounters with Aboriginal Australians – encounters which, among many other fruitful exchanges, allowed ‘kangaroo’ to enter the English language. The Endeavour then sailed north through the Torres Strait, stopped in the East Indies, rounded the Cape of Good Hope and headed home along the west coast of Africa.

The voyage had precise scientific and political aims, but it was also unique for being the first time that a large party of scientists and artists were taken on board, with the sole aim to record and analyse the many plants, animals and peoples they would encounter. Cook’s voyage not only amassed a vast number of natural and ethnographic ‘specimens’, but thousands of pages filled with accounts of Polynesian customs. Some of these records were so thorough, that their authors might well be considered the very first ethnographers of the Pacific. The most remarkable of these proto-ethnographers was the young Joseph Banks. When questioned by alarmed members of his family about why, unlike his peers who complemented their education by touring the ancient ruins of Europe and the Mediterranean, he wished to sail into the uncharted Pacific with little hope of ever coming back, Banks reputedly replied that ‘every blockhead does that. My Grand Tour shall be one around the world.’ Banks never returned to the Pacific, but the example he set with his companions influenced many subsequent voyages and revolutionised the practice of science.

I have spent the last few days daydreaming about what traces of this extraordinary voyage we may find in the wreck of the Endeavour. Unfortunately, as the ship changed hands so many times after its return from the Pacific, the likely answer is not many. We could, however, still hope to see signs of the extensive repairs the Endeavour underwent after striking the Great Barrier Reef, testament to the grit and resilience of its crew.

The excavation of the Endeavour will probably prove far less exciting than that of the wrecks of la Boussole and l’Astrolabe, Jean-François de La Pérouse’s two ships, which were formally identified in 2005 off Vanikoro in the Solomon Islands, still filled with the remains of equipment from an extravagant expedition that was Louis XVI’s response to the Cook voyages. But the lumps of wood from the Endeavour’s hull still carry more significance. The sheer amount of coverage this discovery has received is testament to the enormous importance this unassuming, unremarkable little ship has taken on in the collective imagination. For some the Endeavour is a positive symbol of the foundation of Australia, for others, the first step towards the ruthless annihilation of the Australian continent’s Aboriginal peoples. While celebrating the Endeavour’s discovery, and through it Cook’s extraordinary achievements, we should also take a moment to reflect on the huge and lasting impact this small ship had on hundreds of thousands of lives in the South Seas.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

Share

Recommended for you

Resurrecting the Fallen Feather Gods of Polynesia

‘Missionaries and Idols in Polynesia’ at SOAS reviewed

Who owns the wreckage of the San José, and what should be done with it?

High drama under the high seas and issues of ownership and patrimony off the Colombian coast

Review: ‘The Art and Science of Exploration’ at the Queen’s House

A new display of art from Captain Cook’s voyages is compelling, but doesn’t quite tell the whole story