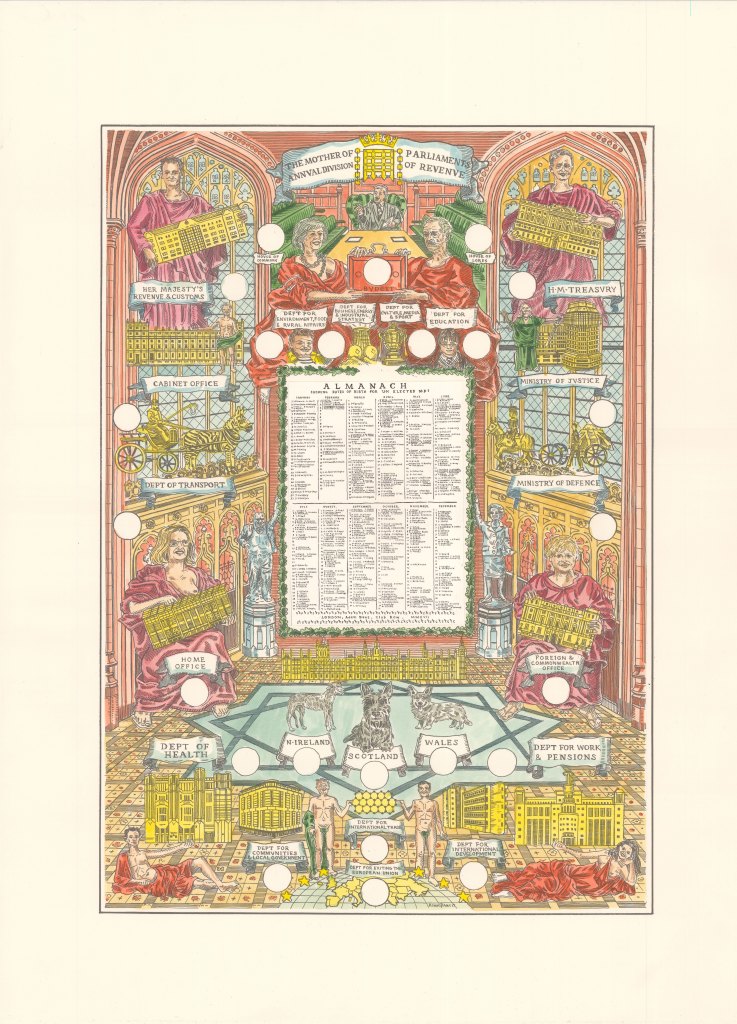

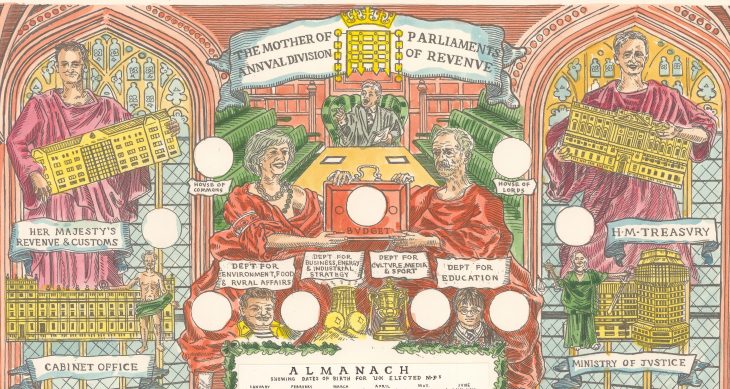

Theresa May and Jeremy Corbyn smile awkwardly at each other clenching the red budget briefcase, as they stand in an otherwise empty House of Commons. Harry Potter symbolises the Ministry of Education. The Ministry of Transport is represented by a dapper Walter de Rothschild, proud in his zebra-drawn carriage. Thus, Adam Dant’s new commission, The Mother of Parliaments, weaves together collections, politics, and family history to put a contemporary spin on the latest exhibition at Waddesdon Manor.

‘Glorious Years: French Calendars from Louis XIV to the Revolution’ focuses on a group of rare ephemera collected by Waddesdon’s founder, Ferdinand de Rothschild. Known as almanacs, these paper calendars were mass-produced sheets that combined rich imagery with annual information on saints days, the lunar cycle, signs of the zodiac, weather, and more. The images allowed for varying complexities of political message to be conveyed, and the exhibition focuses on two high points for this in France – the reign of Louis XIV and the Revolution.

The Royal Concert of the Muses (1671), Marguerite Van Der Mael. Photo: Mike Fear © National Trust, Waddesdon Manor

Louis was the master of political imagery, and the almanacs from his reign mark important births, marriages, battles, and political victories. The complexity of allegory involved suggests direct involvement from the court. Almanac for the Year 1680 (The Effects of the Sun) shows Louis as Apollo in his chariot bringing ‘the effects of the sun’ to Europe in the form of the peace treaties of Nijmegen. These one-page, relatively cheap pieces of annual stationary allowed the political message of the monarch to be brought into homes all over France. The curator Rachel Jacobs, has carefully included print ephemera in the exhibition, which allows her to talk about who would have been able to buy these almanacs and how. Their cheap ubiquity, paradoxically, made them unusual survivals, one of the many ephemeral collections for which we must thank Ferdinand de Rothschild.

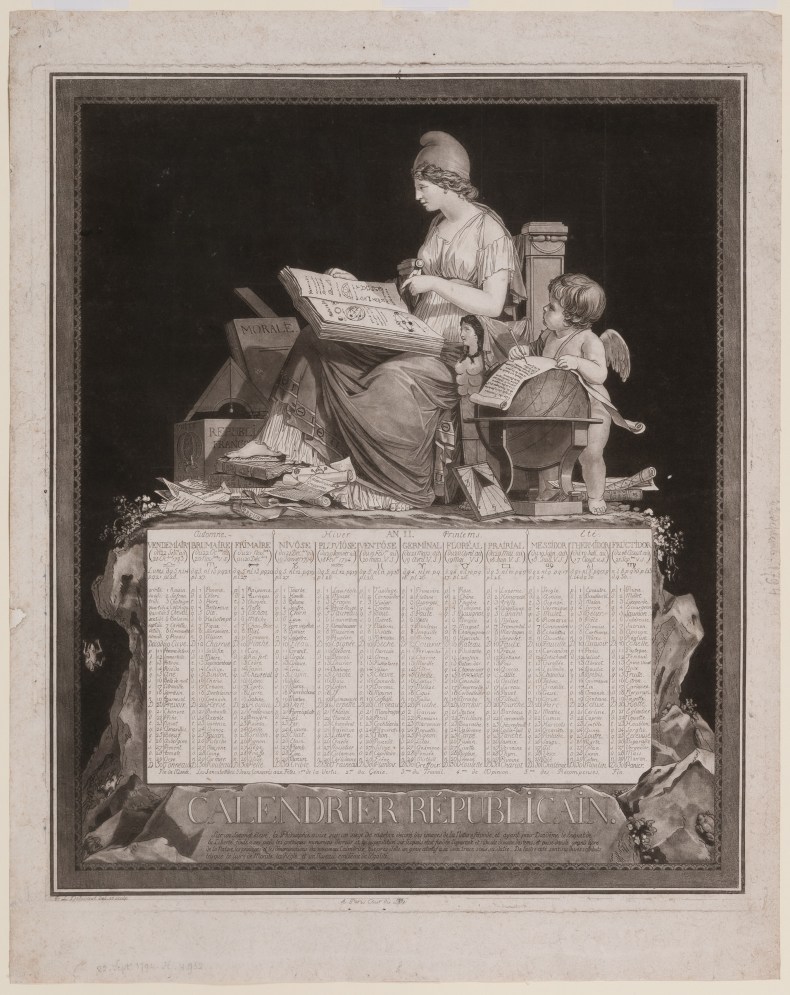

Republican calendar (1794), Philibert Louis Debucourt. Photo: Mike Fear © National Trust, Waddesdon Manor

The French Revolution made calendars even more political, by reorganising and renaming the entire structure of the year. It is unsurprising, then, that this period saw a resurgence of almanacs, after a decline in their style and number after the death of Louis XIV. Parisian printer Philibert-Louis Debucourt made the political power of this restructuring particularly clear in his two prints which pair the calendar for 1794, overseen by the figure of Philosophy, with the figure of the French Republic sitting above the declaration of the rights of man.

Almanacs were also not just for your wall. ‘Glorious Years’ also includes a selection of pocketbook versions, from exquisitely decorated examples, to uncut sheets of images. More pages allowed these almanacs to feature a wider variety of content: ‘a calendar, songs, stories, engravings, and a notebook with erasable paper’. Examples also include stories and anecdotes on current affairs, or space to note accounts, ideas, and poems. ‘A useful pocketbook for all occasions, not dissimilar to our modern-day Smartphones’, these almanacs were complex paper technologies.

The Mother of Parliaments: Annual Division of Revenue, A Print for The British Electorate, 2017, Adam Dant. © the artist

This nice comparison with present-day technology brings us back to Adam Dant. To accompany the exhibition, Waddesdon has commissioned him to create a modern-day almanac weaving together contemporary politics with Rothschild history to show the power of these ephemeral sheets. Dant has chosen to focus on the ‘grey facade of civil service life’ by replacing the French monarchy with MPs and government departments. The almanac at the centre features MPs birthdays rather than saints’ days, and cartouches allow for the departmental budget to be entered each year.

Dant describes The Mother of Parliaments as ‘suitable for hanging on the walls of every British kitchen in place of the ubiquitous kitten calendar or stately home tea towel’’ summing up perfectly how insidiously – and beautifully – such paper products bring politics into our lives, both then and now.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home