The camera’s objectifying – and implicitly male – gaze has been a topic of discussion for some time, particularly when that gaze is directed at women. What happens, then, when the photographer is herself a woman? ‘Who’s Afraid of Women Photographers?’, the sweeping two-part exhibition at the Musée de l’Orangerie and the Musée d’Orsay, offers one possible answer – or rather, 165 possible answers, one for each photographer included in the show.

Mrs Herbert Duckworth (12 April 1867), Julia Margaret Cameron © Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France

Tracing the contributions of women photographers through the medium’s first 150 years, the exhibition jettisons the old narrative of objectification in favour of a new one of individuality and empowerment. And as the title’s allusion to Virginia Woolf suggests, this new narrative exalts equally in women’s contributions to the history of photography – unparalleled in the history of the visual arts because of photography’s recent arrival and democratic accessibility – and in the literal and metaphoric spaces the camera has, in turn, opened up for women and enabled them to create.

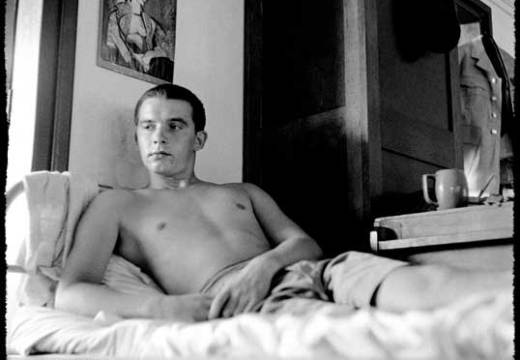

The earliest photographs, on display in the Musée de l’Orangerie (which covers the period 1839–1919), are also those whose content is most circumscribed. Early female practitioners were bound by the gendered social structures of the 19th century, which restricted the public spaces open to women (and in France, kept various professional and amateur photographic associations closed to women). Yet despite these limitations, the camera had an emancipating influence. The domesticity of these early photographs is remarkably subversive, as women photographers used the medium to explore gender, sexuality, and social roles in disconcertingly modern and varied visual terms. In Lady Frances Jocelyn’s emotionally charged interior architecture, in Lady Clementina Hawarden’s off-putting portraits of her daughters and male visitors, in Alice Austen’s remarkable (and slightly later) exploration of female friendship and lesbian desire, the camera deftly deconstructs the feminine sphere it seems so faithfully to represent.

By the turn of the 20th century, the camera was capturing and contributing to a world of ever-broadening horizons, as women enjoyed increasing political and social freedoms – and took the photographs to prove it. The conclusion of the first part of the show offers a taste of things to come in its war and suffrage photographs, but in the second part at the Musée d’Orsay (which covers 1918–1945) there is a seismic shift. Over the course of a mere half century, the early constraints of domesticity were cast off, making way for an astonishing variety of subjects, from nudes to war imagery, portraits to photo-montage, exotic travel images to fashion shots. The encyclopaedic variety of the Musée d’Orsay display is related to, but not a mere reflection of, swiftly changing historical realities. Any stereotypes about acceptable artistic subjects or ‘female’ photographic vision dissolve in the face of this diversity. The objectifying male photographic gaze is banished. The camera emerges as a simple tool of visual expression, wielded not by an archetypal ‘Woman Photographer’ but an army of diverse women photographers.

This is not to say that the show provides no reflection on shared female experience as expressed through photography. It is full of portraits, self-portraits, and nudes that explicitly confront issues of gender, sexuality, and identity. These reflections on womanhood, however, are all the more compelling because they are not shoehorned into a single narrative. Visions of the body include everything from Photo-Secession art nudes to Lee Miller’s Severed Breast from Radical Mastectomy; motherhood runs the gamut from Gertrude Käsebier to Diane Arbus; female identity encompasses Julia Margaret Cameron’s ghostly beauties and Lisette Model’s disconcerting Hermaphrodite alike.

Embryo (1934), Ruth Bernhard. Reproduced with permission of the Ruth Bernhard Archive, Princeton University Art Museum. © Trustees Princeton University © Photo courtesy of the Keith de Lellis Gallery, New York

In the end, a unifying principle does emerge out of heterogeneity. For what captivates, ultimately, in these photographs is not the breadth of the world opened up by the camera but its depth, a depth which affirms that the most beautiful, radical, and liberating worlds we construct through art are the ones that are contained within ourselves, whatever our gender.

‘Who’s Afraid of Women Photographers?’ (‘Qui a peur des femmes photographes?‘) is at the Musée de l’Orangerie and the Musée d’Orsay until 24 January.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home