There was a time, back in the 1960s, when New York’s art institutions were distinctly lukewarm about Diane Arbus’s (1923–71) photography. The Metropolitan Museum of Art was on the brink of buying three photographs for a mere $75 each, but thought better of it and decided to buy only two. The Met’s ambivalence mirrored that of audiences who peered at her portraits of sad-eyed women, gauche adolescents, and vaguely crazed performers with a mixture of fascination and repulsion. ‘New Documents’, a 1967 show at the Museum of Modern Art, which also featured Lee Friedlander and Garry Winogrand, won Arbus plaudits, yet, almost every morning throughout its run, assistants had to clean the pictures because so many viewers had spat on them.

In 2016, Arbus is part of the pantheon of post-war American photography. In 1972, a year after her suicide at the age of 48, she became the first American to have photographs displayed at the Venice Biennale. Catalogues of her work have sold hundreds of thousands of copies. She herself has been the subject of hefty, sometimes salacious biographies, and, in an unlikely turn of events for a diminutive and dark-haired Jewish woman, was played by Nicole Kidman in the 2006 biopic Fur.

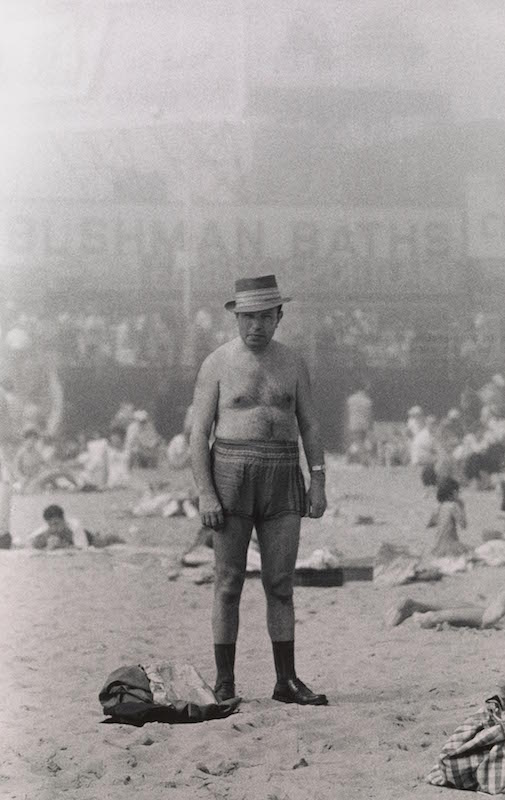

Man in hat, trunks, socks and shoes, Coney Island, N.Y. 1960, Diane Arbus © The Estate of Diane Arbus, LLC

‘Diane Arbus: In the Beginning’, at the Met Breuer, brings together photographs from 1956 to 1962. This was the period when Arbus, who had been given her first camera as an 18th birthday present by her husband (she started out styling fashion photographs for him), struck out on her own, taking a roll of 35mm film and labelling it ‘#1’. Over 100 gelatin silver prints – stored in basement boxes during her lifetime, most of them of never-before displayed images – are exhibited on floor-to-ceiling panels that run across a single gallery. They’re presented neither chronologically nor in thematic clusters. These grainy, close-up, and medium shots of ambiguous urbanites don’t advance anything approaching an argument. Nor do they justify the view of curator Jeff L. Rosenheim, writing in the show’s catalogue, that ‘from the start, Arbus saw the street as a place full of secrets waiting to be fathomed’.

It’s not uncommon to hear Arbus described as a detective, a seeker, some kind of forensic urbanist. Her mentor, the Austrian émigré Lisette Model, had encouraged her to think of the camera as ‘an instrument of detection’. But at the Met Breuer, Diane Arbus seems more of a bricoleur and a semi-bored collector of tics and gestures. It’s as if she were an accidental transatlantic associate of Humphrey Jennings who, in his original Mass Observation manifesto of 1937, asked researchers to explore near-surreal ‘problems’ such as ‘beards, armpits, eyebrows’, ‘the aspidistra cult’, and ‘the private lives of midwives’.

Female impersonator holding long gloves, Hempstead, L.I. 1959, Diane Arbus. © The Estate of Diane Arbus, LLC

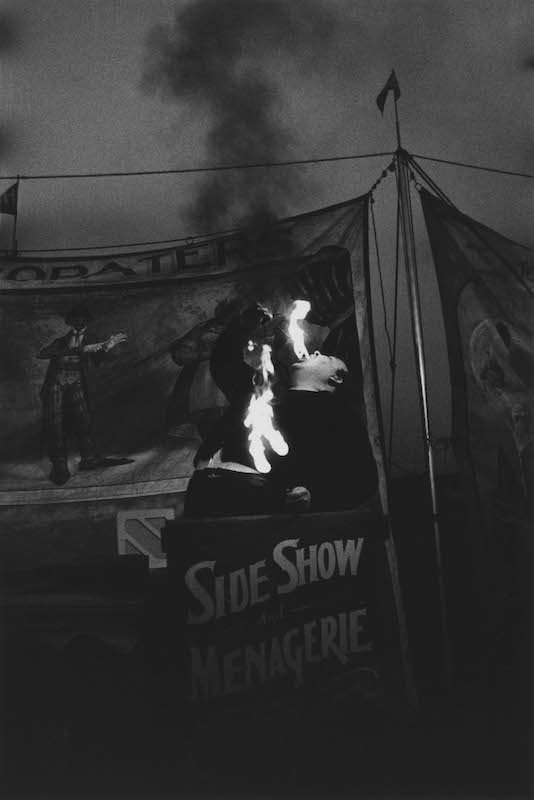

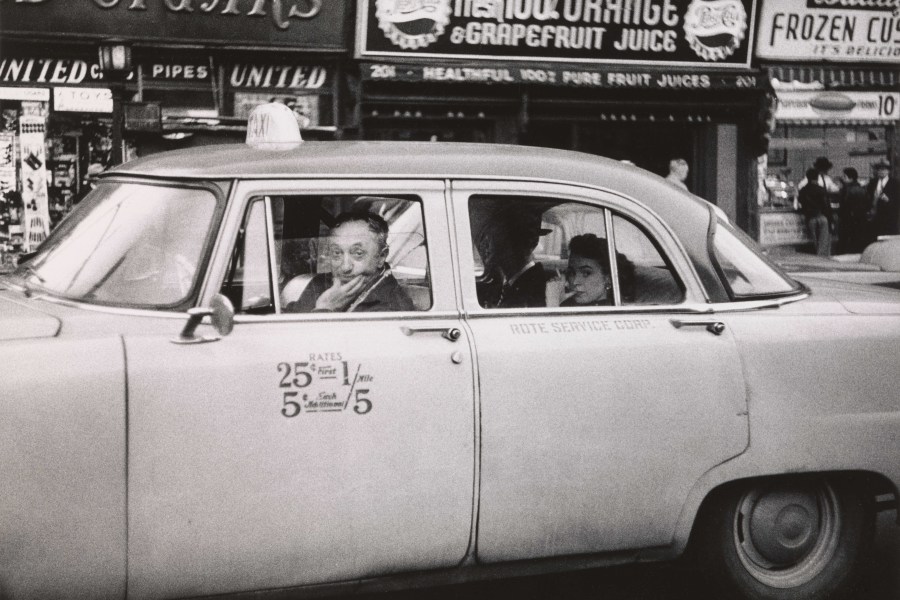

The exhibition presents curiosities without cabinets: a Russian midget, a kid in black face, a man yelling in Times Square, a contortionist. There is more than a touch of the macabre: dead pigs hanging at the slaughterhouse, a headless woman, a human cushion, a contortionist in a hotel room. One picture has a mordantly bathetic caption – ‘corpse with a receding hairline and a toe tag’. Female impersonators and sexually ambiguous figures proliferate, too. Elsewhere there’s a blonde receptionist who looks like a department store mannequin; James Dean in a wax museum; and Siamese twins in a carnival tent. Many photographs are taken at night and some are blurry, almost voyeuristic. Lots are taken in cinemas – here’s Bela Lugosi, there’s Mighty Mouse.

The gap between reality and fiction, between screen and society, the dead and the dead-seeming, between celebrities and tribute acts, even between male and female: all these blur if not wholly collapse. Arbus emerges as a media theorist of cultural convergence, an anthropologist of postmodern America who anticipates and breaks ground for other chroniclers of the cracked, bruised, and hallucinatory such as Larry Clark, Nan Goldin, David Lynch, and Harmony Korine. More than that, she anticipates whole swathes of online visuality – Instagram, Tumblr, Pinterest – where users cultivate and display their notionally off-kilter sensibilities through assembling images of the quirky, zany, defective. It’s a tribute to Arbus’s distinctive vision (though one that she might rush to repudiate) that many of the photographs in the Met show could be from the pages of Vice magazine.

Fire Eater at a carnival, Palisades Park, N.J. 1957, Diane Arbus. © The Estate of Diane Arbus, LLC

That vision has long repelled many viewers. Susan Sontag famously argued that Arbus’s photography was ‘based on distance, on privilege, on a feeling that what the viewer is asked to look at is really other’. One of the show’s side rooms features photographs by the likes of Helen Levitt and Sid Grossman. Their streetscapes are tender and teeming, full of play and politics and possibility – everything that Arbus’s are not. But it’s precisely the coldness and loneliness of her images – the impression they give that both its subjects and maybe even its viewers are trapped in the now – that makes them so discomforting today.

‘Diane Arbus: In the Beginning’ is at the Met Breuer, New York, until 27 November.

From the October issue of Apollo: preview and subscribe here

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home