The Highland clans with sword in hand.

Frae John o Groats tae Airlie

Hae tae a man declared to stand

Or fa wi Royal Charlie.

The old Jacobite hymn might conjure up images of shaggy Scotch clansmen howling depredations at their English adversaries, but anyone hoping to encounter the Hollywood version of the Highlander at the National Museum of Scotland’s excellent exhibition on ‘Bonnie Prince Charlie and the Jacobites’ will be disappointed. The Jacobite pretenders and their supporters appear here not as unruly warriors but as participants in a sophisticated, multicultural court in exile, first in Paris, then in Rome, that drew Catholics and Protestants, Scottish, English, Irish, French, and Italians into its firmament.

The deposition of King James VII and II in 1688 was celebrated at the time for its comparative bloodlessness. Yet it cast a 60-year shadow over Britain. In due course, it led to the deaths of thousands and the evisceration in northern Scotland of an entire way of life. The Glorious Revolution is nowadays seen as the root of constitutional government in the British Isles, but this exhibition reveals how attractive and durable alternative visions remained. James VII and II, his son James (who succeeded him as Jacobite claimant in 1701), and his grandsons Charles and Henry believed that they were kings by divine right and clung to the Catholic faith that had cost them the throne in the expectation that God would eventually restore the proper order.

Gold fob seal with the head of James Francis Edward Stuart, with an impression in red wax. National Museums Scotland

On display here are medals of James VII and II and his descendants, which proclaim them sovereigns of the British Isles ‘by the grace of God’. A similar message is conveyed in Jacobite portraiture. In Nicolas de Largillière’s 1695 painting of the young Prince James, for example, a greyhound turns its head upwards towards the boy, as though nature itself is acknowledging him as rightful heir to the throne.

The most conspicuous way in which the Jacobite monarchs emphasised their divine calling was through the exercise of the royal touch – the God-given power to cure scrofula. The exhibition contains several touchpieces given by James II and his heirs to supplicants, testifying to the scrupulousness with which they maintained this custom. This practice was especially important in the reign of William and Mary, whose Calvinist leanings led them to dispense with it.

The exhibition offers other fascinating glimpses of a pan-Stuart culture bridging the English Channel. During Anne’s reign in particular, the Jacobite court at Saint-Germain-en-Laye came to mirror the Stuart court at Whitehall – or was it the other way around? Along with reintroducing the practice of touching for scrofula, Anne resumed making appointments to the Order of the Thistle, the Scottish chivalric fraternity founded by James VII and II in 1687. William and Mary, embarrassed by the order’s associations with their discredited predecessor, who had used it to reward Catholic supporters, had tried to kill it off, but James and his son continued to add to its ranks across the water, albeit – if the example in the exhibition is typical – using a crude version of the insignia. Queen Anne evidently felt the need to emulate this example. when she succeeded them judiciously reintroduced the custom.

Locket consisting containing a miniature of Prince Charles Edward Stuart, with four pieces of his hair gummed on the back, court (n.d.). National Museums Scotland

On the Jacobite side, there were also subtle attempts at repositioning, not least to make the cause more palatable to the British public. After his father’s death, the younger James refrained from having himself painted with a crown in order not to cause offence in Britain. Instead, he cast himself as heir apparent to Anne. Paintings of James VII and II and his family, surrounded by flora and fauna, had long pointed to the fecundity of the dynasty, in contrast to the barrenness of William and Mary and of Anne. His son took this one step further, commissioning a medal with Anne’s head on one side and his own on the reverse, presenting him as sovereign-in-waiting.

The alignment of the two cultures lasted only until George I’s accession in 1714, which dashed James VIII and III’s hopes of acquiring the British crown peaceably. This prompted a Jacobite rising the following year, joined belatedly by James himself, who landed in Scotland in December 1715 and was proclaimed king in a drumhead ceremony (the improvised swords of state used on the occasion appear here). Despite early successes in northern Scotland, the challenge faltered as Jacobite forces headed south, and James fled back to France.

It would be 30 years before another rising was made in the name of the Stuarts, by which time James had ceded effective leadership of the Jacobite cause to his eldest son, Charles. The experience of 1715 had taught the Jacobite leaders that their strongest support lay in Scotland. The exhibition reveals the lengths to which Charles, who had spent his entire life in Italy, went to present himself as a Scottish laird in anticipation of his invasion. From around 1740, he began appearing in Rome wearing plaid, ‘which became him very well’, according to one observer. The exhibition contains a magnificent tartan suit similar to one worn by Charles, along with a portrait miniature of him in Highland dress. It also presents a fine selection of objects created to allow Scottish Jacobites to demonstrate clandestine support for the cause, from snuffboxes with double lids to glasses engraved with allusive symbols, such as half-opened rosebuds and moths flying towards the sun.

Fan with a hand-painted leaf showing Prince Charles Edward Stewart surrounded by classical gods (c. 1746), probably designed by Robert Strange. National Museums Scotland

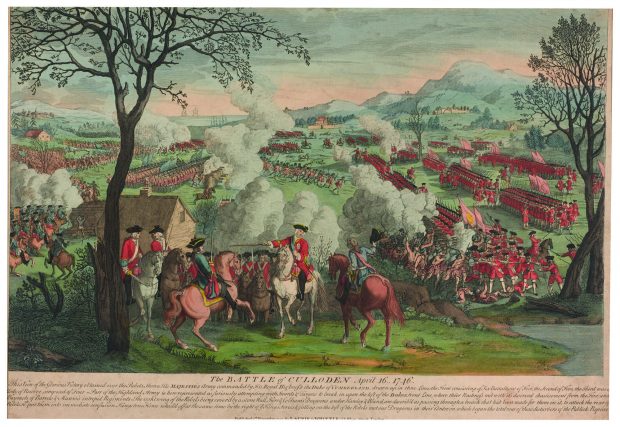

Charles’s makeover initially paid off. Upon landing in the Highlands in August 1745, he was able to rally the clan leaders to his standard. In little over a month, almost the whole of Scotland was under his control and he was holding court in Holyrood Palace in Edinburgh, touching for scrofula and hosting balls for local beauties (several dresses allegedly worn to dances there appear here). As with his father, Charles’s attentions were drawn towards England. Indeed, the sole portrait of him painted in Edinburgh depicts him wearing the insignia of the Order of the Garter (it was rapidly engraved for distribution south of the border). Nevertheless, England proved the Jacobites’ nemesis. Charles and his army reached Derby before government troops forced them back towards Scotland. They were eventually routed at Culloden in April 1746, with Charles barely escaping with his life.

The Battle of Culloden marked the end of Jacobitism as a serious political movement. Its demise was hastened, as this exhibition shows, by the very Catholicism that had sustained the Stuarts throughout their long exile. Charles, increasingly in thrall to alcohol, failed to produce a legitimate heir, while his brother, Henry, took holy orders, condemning himself to a life of chastity. This final act of dynastic suicide seems a fitting end for a family that repeatedly put faith before self-interest, with disastrous consequences.

‘Bonnie Prince Charlie and the Jacobites’ is at the National Museum of Scotland, Edinburgh, from 23 June–12 November.

From the September 2017 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home