The money shot in Benjamin Ree’s documentary, the moment that has been mentioned in all the interviews, features and reviews The Painter and the Thief has inspired since winning a special jury prize at the Sundance Film Festival at the start of this year, comes surprisingly early. Barbora Kysilkova, a Czech artist who lives in Norway, shows Karl-Bertil Nordland, a drug addict and petty thief, the portrait she has been painting of him. Confronted by this larger-than-life, almost photorealist image of himself, tattooed and pensive, Bertil is awed, puzzled, scared: ‘Whoa!’ he says. ‘Fuck me over! What the fuck?’ And he begins to cry.

It is a moving moment – evidence of what it can mean to feel ‘seen’. At a time so rich in instant image-making and instant judgement, how extraordinary to know that someone has paid you such real, deep attention and that nevertheless they have not swiped left; you are not rejected. But that isn’t what the film is mostly about; it is at least as interested in concealment and evasion, how we hide from others and from ourselves.

The backstory to that climactic unveiling began in early 2015 when two of Kysilkova’s paintings were stolen from a commercial gallery in Oslo. We see the CCTV footage: the thieves – Bertil and another man, who is not named and appears only very briefly in the film – were easily identified, and arrested. At a court hearing Barbora approached Bertil and asked him (in English) why he had stolen her painting; he answered ‘Because they were beautiful’. She responds by suggesting they could meet some time: ‘I’d love to make a portrait of you.’ It sounds jarringly like a chat-up line, and though that kind of romance doesn’t happen (she’s in Oslo to be with a nice man called Øystein), there are other moments to remind you that erotic connections between artists and models are not only a cliché – as when Barbora is seen looking at one of Bertil’s selfies, smartphone and shirtless torso in a mirror, the kind of shot he might send to a girlfriend, or put on his Tinder profile.

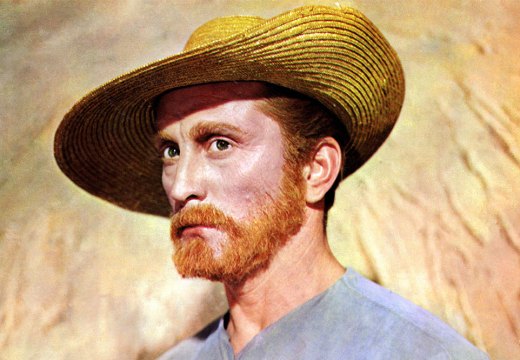

A detail from one of Barbora’s portraits of Bertil. Courtesy Neon

In fact, the film is less a romance than a mystery story. One mystery is where it all went wrong for Bertil, seemingly a talent student, athlete and craftsman, but haunted by a sense of being unwanted or unworthy: his tattoos include several roses which symbolise, he explains, an unhappy childhood. Another mystery is what happened to the stolen paintings – a question Barbora presses, though Bertil seems perfectly sincere when he tells her he was too out of his head to know; and towards the end her persistence yields a twist. But this doesn’t account for her pursuit of Bertil.

At the start, the camera seems to take her point of view, and there is a slight impression of condescension to the poor, messed-up addict. But even as Bertil’s mess gets worse, as he skips rehab, is thrown out by his girlfriend and crashes a stolen car, it becomes clear that Barbora’s life is not a straightforward success. ‘She sees me very well,’ Bertil tells Ree, ‘but she forgets I can see her too.’ The perspective shifts: we see Barbora struggling to find a gallery to show her work, having her bank card rejected in a supermarket, breaking down over a voicemail message demanding back rent on her studio; she has escaped an abusive relationship, we learn. She is more willing to scrutinise Bertil than to be scrutinised herself.

The all-encompassing mystery is what the film is up to. It dodges back and forth, offering tidbits of information and insight, never giving away too much or allowing a consistent picture to emerge. The film-maker’s presence is never acknowledged or explained and it is not clear at what point he arrived in the story, or how much he intervenes – some scenes have a staged, or at least unspontaneous quality. Ree’s film itself seems to lean towards photorealism: at first sight, you could easily mistake it for unvarnished actuality; look closer, and you see how composed and artificial it is. And in the end the viewer might wonder who, exactly is painting whom here, who is the thief, and what has been stolen?

The Painter and the Thief is available to rent in the US and Canada; it will be released in the UK at a later date.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home