Geta Brătescu died on 19 September at the age of 92. Exactly one week afterwards, an exhibition of her work opened at Neuer Berliner Kunstverein (NBK), in what is the Romanian artist’s first institutional show in Berlin. Unfurling from the gallery’s small first-floor showroom space out on to an adjoining wall, the exhibition is modest in scale. But while small, it is a rich and considered collection of film, sculptures, and paper-based works, made between 1970 and 2018, which communicates many of the ideas central to Brătescu’s long career. A bird motif is tracked back as far as 1970; the idea of the studio, sacrosanct to Brătescu, links the large lithographic work Atelierul (The Studio, 1970) to the film Gestul, desunul (The Gesture, the Drawing, 2018), made in collaboration with the artist Ștefan Sava only a few months back. Planned far in advance – showing me around, the curator and Brătescu’s long-term collaborator Magda Radu, tells me the idea behind it originates in 2016 – the exhibition has now become a concise snapshot of the artist’s practice, a body of work that will continue to acquire new meaning even now that she is gone.

Installation view of ‘Geta Brătescu’, Neuer Berliner Kunstverein, 2018. Photo: © Neuer Berliner Kunstverein/Jens Ziehe

Born in the small city of Ploiești in 1926, Brătescu remained in Romania for her entire life. Taking place against the backdrop of the Second World War, Soviet occupation, and the harsh repression and austerity initiated by Nicolae Ceaușescu after his ascent to power in 1965, her artistic life was an unlikely one, constructed in the face of consistent national trauma. It hardly bears stating that another artist may well have attempted to leave. But while Brătescu enjoyed travel, Radu tells me, her preferred mode of movement was that granted by the imagination. Her studio was, and remained right up to her death, a space for limitless freedom and experimentation – unrestrained flight, like the bird that runs through the exhibition at NBK. She was expelled, due to her middle-class roots, from the Academy of Fine Arts by the ruling Communist party in 1949; it was not until 1969, when she returned to school at the Institute of Fine Arts, that she finally had a studio of her own. This space would engender some of Brătescu’s best-known early works, including the photo series Către alb (Towards White, 1975), and Atelierul (The Studio, 1978), the 8mm film made in collaboration with Ion Grigorescu. Brătescu’s retreat to the studio was not an apolitical, hermetic gesture; rather, her work made there cast the increasingly savage outside world into sharp relief.

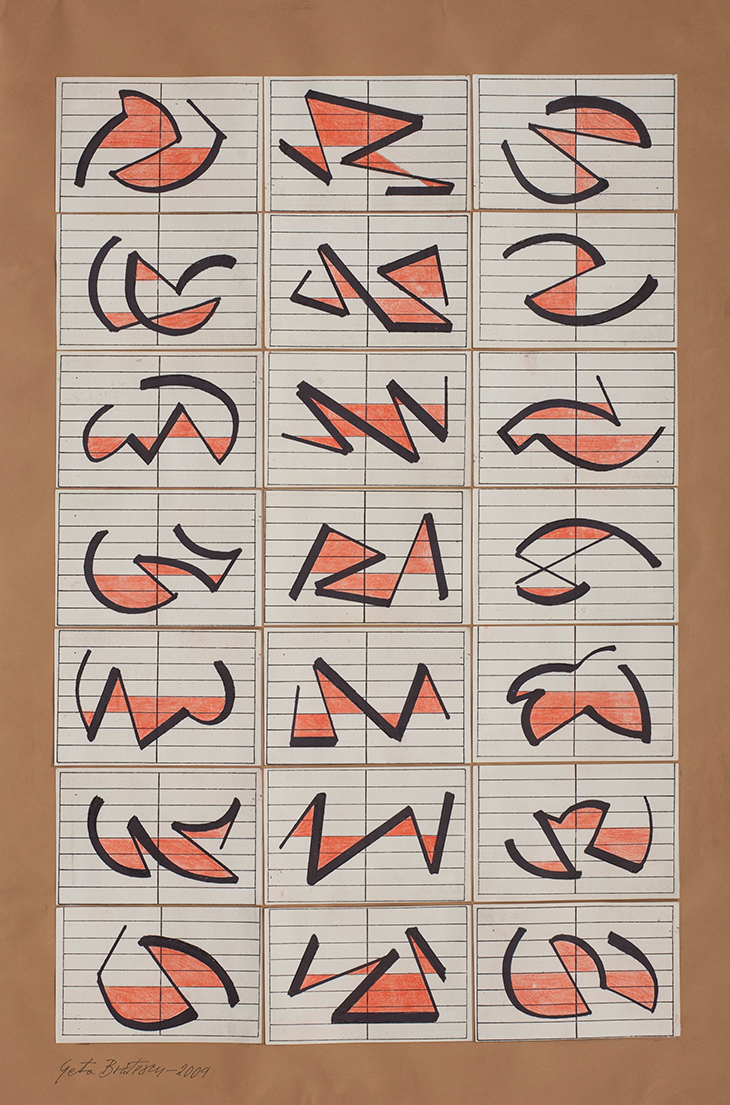

This utopian view of the studio, and creativity in general, did not turn cynical with age. Though in later years it moved from the Art Institute to a room in her Bucharest home, the studio remained a sacred space. In Gestul, desunul, the film made specifically for this exhibition, we see the artist at her desk. Visibly frail though she is, she speaks slowly and deliberately about her work – the importance of drawing, and the line in particular – as though measuring every word. She works as she talks, with close-ups of her papery hands as they draw and cut paper. At certain points she asks her interviewer’s opinion on particular decisions, but we get the sense this is more Brătescu’s politeness than anything else. The act of drawing, she says at one point, has provided her with ‘permanent continuity, from childhood to the present day’. Young or old, when she sat down at her desk in the studio, the challenge had not changed: how to create a drawing that registered gesture, space, movement, as dance communicates the body. ‘If you don’t have this feeling of the line’s objectivity,’ she warns, ‘I don’t think the drawing itself will end up coming alive on the paper.’

Linia (2009), Geta Brătescu. Photo: Ștefan Sava. Courtesy Ivan Gallery, Bucharest and Hauser & Wirth; © the artist

It was ‘Apparitions’, the Romanian pavilion exhibition at the Venice Biennale in 2017, also curated by Radu, that consolidated Brătescu’s reputation so late in her life on the international art stage. But she had gained recognition in her home country long before. As Radu shows me around NBK, she tells me of frequent visits to Brătescu’s studio; sometimes, she went with a project in mind, sometimes she simply wanted to be in her company. Still using the present tense when talking about the artist, Nadu describes her as a ‘very inspirational’ person. She never fussed over the curator’s studio visits, nor was she inclined to make professional displays. Instead she was always working, creating art ‘from whatever comes into her orbit’. There found materials, such as the series of National Geographic envelopes addressed to her husband that form the basis of her work Călătorul (The Traveller; 2006), are transformed into something entirely new. With her use of material, as Radu puts it, there simply was ‘no hierarchy’. Brătescu was an artist entirely open to the serendipitous drift made available by these outside things. As she worked at her desk, they took on a new, free kind of sense.

‘Geta Brătescu’ is at Neuer Berliner Kunstverein, Berlin, until 26 January 2019.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home