In 1944, Vincente Minnelli directed Judy Garland (his future wife) in the much loved movie Meet Me in St Louis, about four sisters visiting the city in the lead up to the 1904 World’s Fair. Most of us can sing along with Garland as she invites, confusingly, her own Louis to, ‘Meet me in St Louis, Louis, Meet me at the fair, Don’t tell me the lights are shining any place but there, we will dance the Hoochee Koochee, I will be your tootsie wootsie, If you will meet in St Louis, Louis, Meet me at the fair.’

The city was riding high in 1904. Pierre Laclede and Auguste Chouteau founded it in 1763 as a fur-trading post where the great Missouri and Mississippi rivers meet, naming it after their king, Louis IX. In 1803 it was part of the US’s Louisiana Purchase, and the following year it was from here, capital of those new territories, that the Lewis and Clark Expedition set off to westwards to explore uncharted lands. The city prospered with trade, immigrants (many of them German), steamboats on the river (from 1818), and railways on the land (from the 1850s). By mid-century, Henry Shaw, an adventurous British trader from Sheffield, was importing Kew gardeners to lay out what is now Missouri Botanical Garden, one of the finest of its kind, and a young Charles Dickens had visited the city whose population was greater than New York’s. Louis Sullivan would build an early skyscraper there, the 10-storey Wainwright Building.

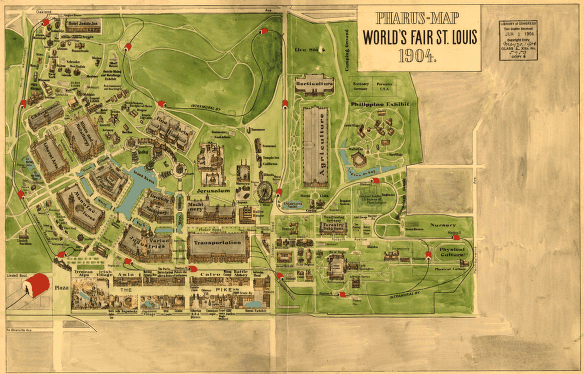

Map of the 1904 World’s Fair in St Louis. Photo: Pharus/Wikimedia commons (used under public domain licence)

In 1904, St Louis hosted both the World’s Fair – officially called the centennial Louisiana Purchase Exposition – and the first Summer Olympics held outside Europe. The fair was spectacular: more than 1,500 buildings laid out by master designer George Kessler in the 1,371-acre Forest Park, with 45 US states and 50 foreign nations exhibiting, and 19 million visitors to enjoy it all.

Today, after some economic wobbles, the city is flourishing with the renovated park as its centerpiece. Here, Saint Louis Art Museum (founded 1881) fills the fair’s Palace of Fine Arts designed by Cass Gilbert and flows into David Chipperfield’s expansion. Its encyclopaedic glories – many given by local collectors from Morton D. May’s Max Beckmans through Joe Pulitzer’s Modigliani and Matisse paintings (among much else), to the Spinks’ recent gift of American and Asian art – will be celebrated in 2017 with shows devoted to Degas, Impressionism, and the Paris Millinery Trade (12 Feb–7 May) and to Old Master drawings given by Phoebe and Mark Weil.

Rieuse (early 1890s), Medardo Rosso. Collection PCC

Having lived in the US for 15 years, I am beginning to be less surprised at finding city museums with astonishing collections in most cities across the country. But in St Louis I was also impressed by a trio of exceptional museums devoted to contemporary art. The Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum in its Fumihiko Maki building lies across from the park, mixing displays of a rich permanent collection with temporary ones (a Roselyn Drexler retrospective in 2017). The two others are found a short walk from Tiffany Studios’ largest work, completed in 1912: the 83,000 square feet of mosaic coating the interior of the Cathedral Basilica of St Louis. One is the Contemporary Art Museum, which bravely staged the Kelley Walker show (Deana Lawson is here in 2017 before being part of the Whitney Biennial).

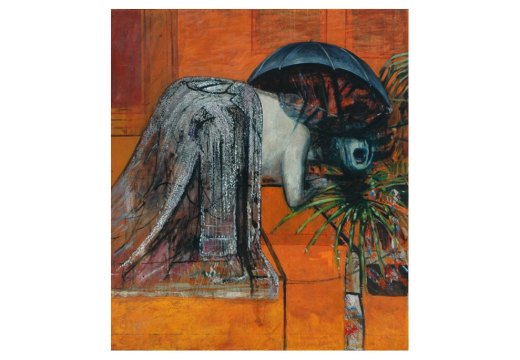

Next door is the Pulitzer Arts Foundation in Tadao Ando’s ravishing building. The Pulitzer does not own a collection; rather, it presents experimental and progressive art. Currently, the galleries are filled with the first comprehensive exhibition in the US of Medardo Rosso (1858–1928), the rebellious, arrogant Italian sculptor from Turin. Sweeping into Paris, he held champagne casting parties in his studio and shook up Rodin’s preeminence – indeed, he took public umbrage when Rodin failed to acknowledge a debt to Rosso in his Monument to Balzac (1898). The 100 works on display include sculptures in plaster, bronze, and wax that are as contemporary as when Rosso made them using innovative techniques that portray his characters with the fleeting, fugitive qualities of ‘a moment captured’. This exhibition alone is worth the journey to St Louis.

St Louis’s sparkling Metro trains stop near the desolate shores of Mark Twain’s murky, slow-flowing Mississippi; but today’s crowds meet in nearby rooftop bars to sip martinis and scan the river’s winding course. Come, meet me in St Louis and let’s dance the Hoochee Koochee.

‘Medardo Rosso: Experiments in Light and Form’ is at Pulitzer Arts Foundation, St Louis, until 13 May.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home