When he was about 47, Pierre-Auguste Renoir began to suffer from terrible pain in his eyes and teeth. He knew something was wrong, possibly permanently wrong. ‘What’s going to happen after this? I really can’t travel in the state I’m in… Tomorrow, I hope my eye will open up and I can finish my paintings,’ he wrote to his friend and dealer Paul Durand-Ruel, in December 1888. It was the onset of severe rheumatoid arthritis that would curtail the ways he could use his hands and body almost immediately.

Renoir lived to be 78 years old, and he went on painting nearly every day that he was not confined to bed. In her new book, Barbara Ehrlich White details the ingenious techniques that allowed him to do so. Renoir had his model or his children put the brush into his hand and take it out when he was done; sometimes he painted with both hands together cramped around the brush. White dispels the rumour that the paintbrush was tied to his hands. There was no need, his hands were so contracted, but ‘to avoid ripping the fragile skin of his palms with the wooden handle of his paintbrush, a little piece of cloth was inserted in his palm held in place with linen strips tied round and knotted at his wrists’.

Lise in a White Shawl (1872), Pierre-Auguste Renoir. Dallas Museum of Art, Texas

Renoir had always hated being alone and now he really could not paint alone. Late in life he wrote to a friend about a persistent state of mind, ‘What I feared was isolation.’ The word ‘intimate’ in White’s subtitle is doubly suggestive. She portrays a personal battle to continue painting, and also draws on a vast amount of private correspondence, diaries, and notes written by Renoir and the people who were closest to him. This is a book about a man who painted, not about the paintings he made. White begins with Renoir’s working-class background, his apprenticeships, and the ways in which patronage was a necessary fact of his existence. Her account of Renoir’s adult life focuses on a succession of domestic establishments. Early on, Renoir had a mistress, Lise Tréhot, who was his only model from 1866 to 1872. She posed for Lise Sewing, Portrait of Lise, Lise (Woman with an Umbrella), Lise and Sisley, Algerian Odalisque, Lise in a White Shawl (1872) – all the paintings he sent to the yearly Salons. During this time Lise was pregnant twice, and the two babies born were given up for adoption. One, a son Pierre, probably died immediately; the second, a daughter Jeanne, survived. Renoir supported his daughter, eventually giving her his last name, and left her a legacy when he died. Tréhot left Renoir for another lover in 1872. Some seven years went by during which Renoir painted portraits for hire, had many different models, and depicted a social world of friends, painters, dealers – this is the time of Le Moulin de la Galette (1876) – before he met Aline Charigot.

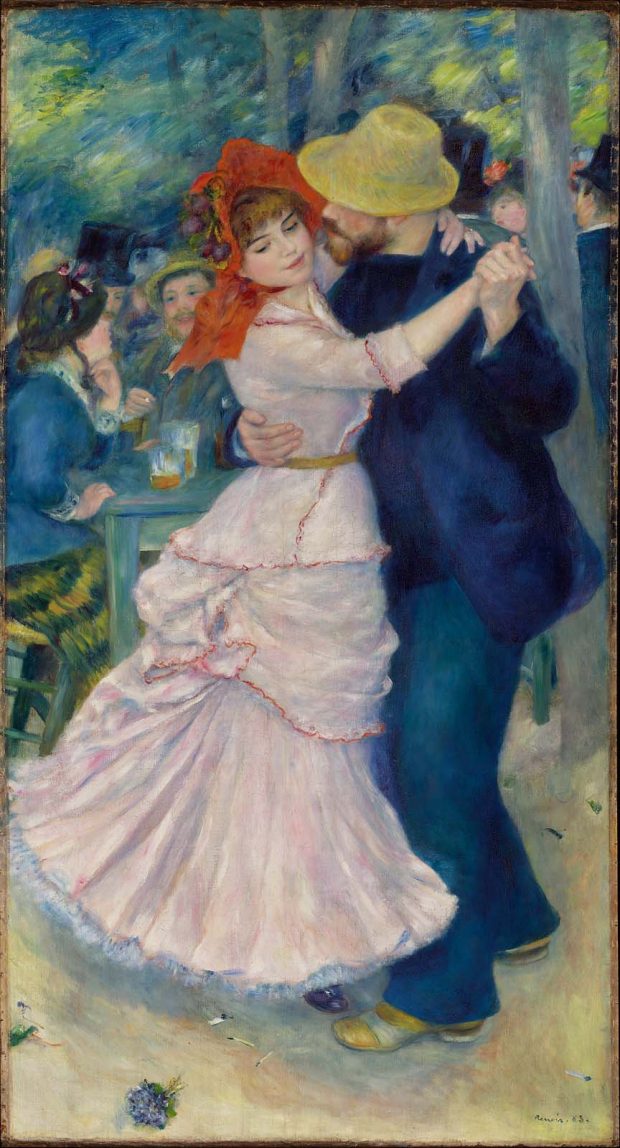

Dance at Bougival (1883), Pierre-August Renoir. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Renoir conveyed nothing of his earlier complex web of relationships to this next mistress and model, who eventually became his wife. Aline was the model for paintings, such as Dance at Bougival (1883), that seem almost as familiar to us as one imagines they did to the people who lived with them as they were made. She is the woman in blue playing with the dog in the left corner who anchors Luncheon of the Boating Party (1880–81). Eventually, the two married and legitimised their first child, also a son Pierre; two more sons, Jean and Claude, were born after the marriage. The Renoirs were close to other Impressionist families, and the painter parents looked out for and painted one another’s children, too. One of Renoir’s closest friends was Berthe Morisot (married to Eugène Manet), and Renoir’s whole family was a great support to Julie Manet after her mother died.

Further domestic configurations followed. Gabrielle Renard, a relation of Aline’s, came to the Renoir household at the age of 15, to work as a nursemaid, and over the years essentially became a third wife and one of Renoir’s most important models. Renard makes a significant entrance into Renoir’s paintings in 1896, when she appears in The Artist’s Family, crouching down to hold a child. Aline Renoir is in this picture, too – the last time she is depicted with their children – and there is a girl with her back partly turned, that White thinks might be an allusion to the missing daughter. After this, other women posed with the children in the maternal role – it is Renard with Jean Renoir in the lovely Gabrielle and Jean (1895–96). For 19 years, Renard was a generous caretaker of Renoir, and another mother to Jean, until she was fired by Aline. White speculates (I think persuasively) that Aline fired Renard when she discovered the existence of Renoir’s daughter. By contrast, Renard not only knew about Jeanne, but visited her and knew her well.

The Artist’s Family (1896), Pierre-Auguste Renoir. The Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia

Renoir has been the Impressionist I have found it most difficult to appreciate artistically; in general, I walk on to other paintings in museums. I did not think I was making any progress while reading Renoir: An Intimate Biography, but when I went back to the Art Institute in Chicago, I was surprised to find that it made a real difference to think of the painter not only as a painter of women and children, but as a painter among women and children. White’s thorough documenting of Renoir’s domestic life makes me see differently the women and children not only in his paintings, but in Impressionist works more generally. In the paintings of lovers and families, as in the portraits the Impressionists made of one another, it is possible to discern not only the painters’ ideas, but something of the models’ ideas about corporeality, desire, tenderness, and dependence. All of which were shared considerations in life and in painting.

In reading the correspondence that White has combed through and presented here, it’s possible to see the frankness with which this was all understood among the community of painters, models, lovers, husbands, wives, children, household workers, gallerists, and collectors. Perhaps it was because Renoir was sociable and funny and kind, and also because his illness meant that he had to be surrounded at all times, that this sense of the community that made the paintings can be more readily perceived in the life around him and in the paintings themselves.

Renoir: An Intimate Biography by Barbara Ehrlich White is published by Thames & Hudson (£24.95).

From the January 2018 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home