Meiro Koizumi’s video My Voice Would Reach You (2009) – installed at the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, as part of its exhibition ‘Tokyo: Art & Photography’ – frames what looks at first like an unremarkable shot of modern Tokyo. The camera puts us at a junction, in a valley of daylight between high buildings, watching as a salaryman stands talking into his phone. Behind him, crowds of pedestrians cross the road, enter shops covered in bright signs; cars pass, life flows. The salaryman calls his mother, reassuring her, in the same tired way that everyone does, that everything’s fine, that he’s okay for money. Then he invites her on a weekend break. We cannot hear what she is saying but his side of the conversation makes it plain enough: maternal refusal to be made a fuss of; the insistence that it’s too expensive and she couldn’t possibly accept. They get cut off. He calls back, insists again that she shouldn’t worry about the money, and begins, as we watch, to become increasingly emotional about her resistance. Only in the second part of the video can the other side of the conversation be heard. It isn’t his mother at all. At the end of the line are call-centre workers, trying to wrap their heads around a dialogue never meant for them, and trying in the finest Japanese style to extricate themselves from it with maximum tact.

My Voice Would Reach You (film still; 2009), Meiro Koizumi. Courtesy the artist and Annet Gelink Gallery.; © Meiro Koizumi

The prank isn’t hollow, though. As Koizumi reveals, the actor is addressing his mother, but his mother is dead. The emotion is real, even if the connection is not. The quotidian conversation he wishes he could have with her is redirected to the puzzled, but polite ears of people expecting an entirely different kind of quotidian conversation. The effect is in part mundane, in part absurd, and, because of the way that the two overlap, genuinely moving. The urban backdrop leaves you wondering about the connections missed by everyone passing the camera. In the context of the exhibition, you wonder too about the ways that the normality of Japan – the everydayness of life there – tends to get ignored by foreign eyes fixated on its strangeness.

Tokyo from Utsurundesu series (2018–present), Mika Ninagawa. Courtesy the artist and Tomio Koyama Gallery; © Mika Ninagawa

My Voice Would Reach You is typical of the approach to life in Tokyo taken in this excellent show. There are the items you might expect: Hiroshige and his followers; a suit of samurai armour; the odd bit of kink in the form of shunga prints and Araki photographs; the often exaggerated kawai kookiness of modern Tokyo, epitomised by a photograph of the pink-haired Amiaya twins from Mika Ninagawa’s Utsurundesu series (2018–present). But overall, this is a show that looks beyond preconceptions to the real city and its artists. As curators Lena Fritsch and Clare Pollard note, a comprehensive survey would be impossible, but their selection does a superb job of focusing on a few key facets of art in Tokyo across the last three centuries. Starting from an 18th-century Dutch map of what was then the shogun stronghold Edo, the show moves thematically and chronologically, first through representations of the city’s geography and architecture, onto images of its inhabitants up to the present, and lastly into its role as a centre for innovation in Japanese art, from the invention of coloured woodblocks in the 1760s, up to Fluxus, the manga-influenced ‘superflat’ movement, and beyond. It stops just short of being too much to take in, though the unsated curious will find even more to chew on in the catalogue, with fine essays by Pollard, Fritsch and other specialists on still other aspects of life and art in the capital.

The Suijin Woods and Massaki on the Sumida River, from the series One Hundred Famous Views of Edo (1856), Hiroshige

Much on display here is simply beautiful. Tokyo – a historically unlucky city in many ways – was blessed in finding Hiroshige (1797–1858) and ukiyo-e to immortalise it in its pomp. Shortly before the Meiji Restoration in 1868, when the city was renamed Tokyo (‘Eastern Capital’), Hiroshige’s One Hundred Famous Views of Edo (1859) plugged into an existing tradition of recording meisho (‘famous places’) and laid down a new marker for technical sophistication and brilliance in doing so. It is easy to forget, in their familiarity, just how compositionally daring his prints are. The calm geometries of the famous landscapes and buildings are repeatedly framed and interrupted by intrusive foregrounds, or hatched over with black streaks of rain: now peaceful, now teeming with the unruly bustle of life.

Illustration of the Ceremony Promulgating the Constitution (1890), Kojima Shogetsu. Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

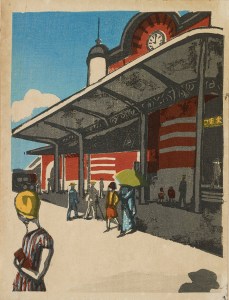

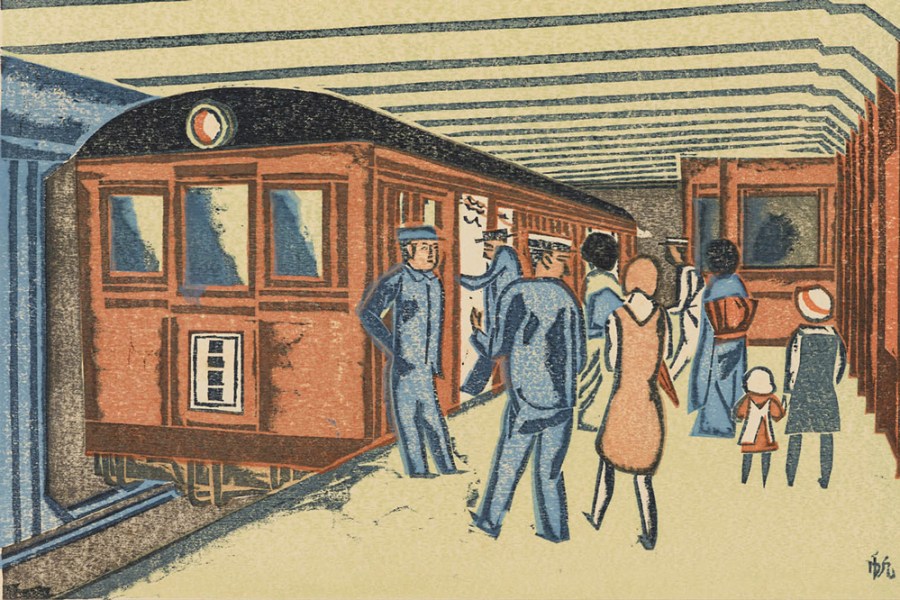

Tokyo Station, from the series Scenes of Lost Tokyo (1945), Koshiro Onchi. Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford. © the artist

The creation of the Hundred Famous Views coincided with the reopening of Japan to the outside world after two centuries of isolationism: a moment that ushered in a period of hyper-rapid modernisation in technology, mores, and social structures. The legions of ‘foreign technical experts’ hired by the Emperor Meiji after 1868 catapulted Japan into a new era through a forced programme of ‘catching up’ with the West. The rapid changes, as the curators here point out, are recorded in two ways by Kojima Shogetsu, whose prints depict the imperial family in Western dress, resplendently coloured with aniline dyes – themselves a new import. Others turned their eyes on the changes that followed disasters: the great earthquakes of 1855 and 1923 (the latter of which claimed 100,000 lives and left two million homeless); the floods of 1910; and the horrific incendiary air raids of March 1945 (which, even considered against Hiroshima and Nagasaki, remain the most destructive in history). The cycle of hope and loss here sets One Hundred Views of New Tokyo (1931) – in which various hands celebrate the rebirth of the city after 1923 – against Koshiro Onchi’s elegiac Scenes of Lost Tokyo (1945); Onchi’s prints gain immeasurably by being carefully positioned in the long view provided here.

If the exhibition concluded in 1945, it would remain an ambitious show. Yet equal attention is given to the changes of the post-war period, in which the floating world of ukiyo-e gave way to the harder-edged realities of photography – shashin, composed of the kanji characters for ‘copy’ and ‘truth’ – as the key form of Japanese visual expression. From nightlife and love hotels to student protests, improvised homeless shelters to water leaks caused by the constant small earthquakes, the second part of the exhibition is less beautiful, but no less memorable – a reminder that Tokyo is a city that could not stop moving even if it wanted to.

‘Tokyo: Art & Photography’ is at the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, until 3 January 2022.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home