‘If I ruled the world,’ sings Lauryn Hill on the chorus of her 1996 collaboration with rapper Nas, ‘I’d free all my sons.’ This vow is firmly hypothetical, as the prospect of a black woman ruling the world was, in the mid 1990s, more inconceivable than it is now. (‘Imagine that,’ Nas ad-libs after the first part of Hill’s declaration.) But if Lauryn Hill ruled the world, would she stick to her word? Or would she find herself corrupted by power and gravitating toward the same tactics of control and terror deployed by her predecessors? This is one of the uncomfortable questions raised by A Countervailing Theory, Toyin Ojih Odutola’s commission for the Barbican’s Curve gallery. Forty drawings on either linen or board narrate the life of a fictional ancient civilisation native to Riyom, an area of Nigeria’s geographically distinct Plateau State. The rulers of this world are the Eshu, women warriors who preside over the land and dominate the labouring Koba, a manufactured race of beings that resemble adult men. Like other aristocrats throughout time and place, the Eshu rule with iron fists, assuming an inborn right to exploit the earth and the powerless.

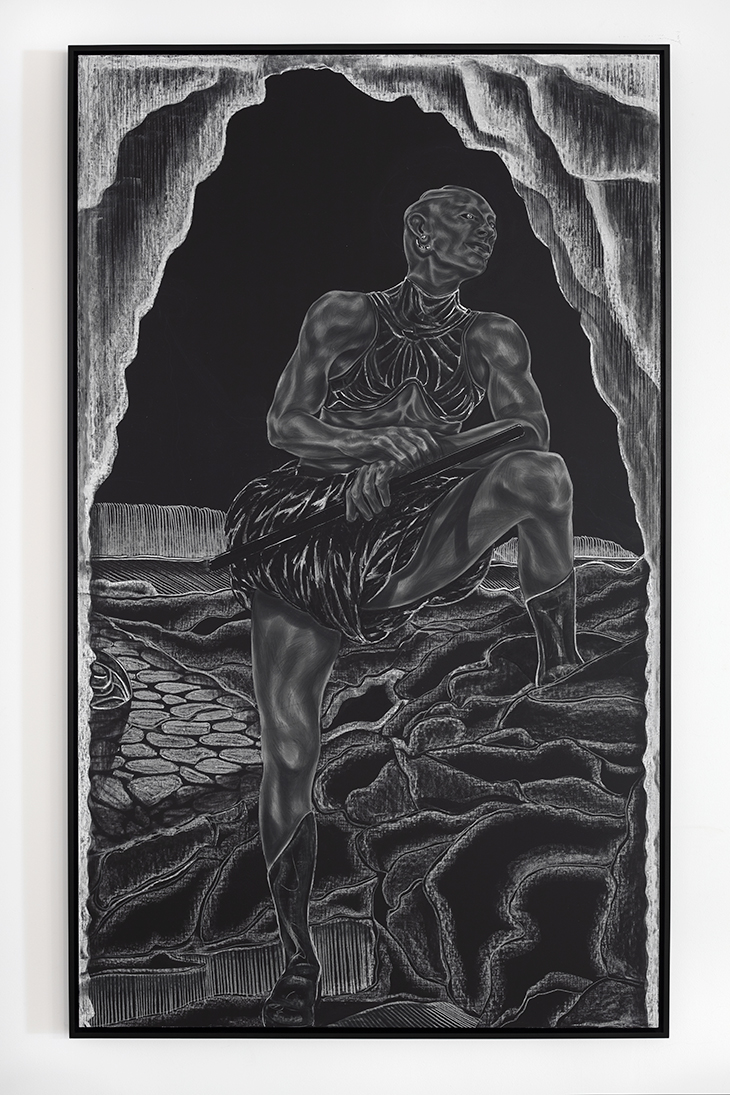

The Ruling Class (Eshu) from A Countervailing Theory (2019), Toyin Ojih Odutola. Courtesy the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York; © Toyin Ojih Odutola

‘A Countervailing Theory’ is less of a conventional exhibition than a dramatic conceptual and multi-sensory experience. Before my visit, I had already read the short catalogue for the display, which features a letter written by Ojih Odutola presenting her works as life-size scans of pictorial markings on a deposit of black shale discovered in Riyom, a place known for its rocks. In the letter, the artist adopts the role of an archaeologist who has been called on to investigate the images, distancing herself further from her achievements by stating that they appear to be created by more than one author. Staging the works as life-size scans plays on the prejudices that have historically prevented ancient African art, and other relics from the Global South, from being seen as aesthetic objects. The irony is that these drawings are the ultimate aesthetic objects, and in no way could they be taken for digital reproductions. Throughout the display, I remain in awe of the textures Ojih Odutola is able to achieve with pastel, charcoal, and chalk. The artist pushes the materials to their sensual limits, allowing each passage of flesh, rock, soil, water, textile, and foliage to pulsate with its own frequency. And all without the support of colour: everything in the space is monochrome.

The idea of these exquisite drawings being scans of ancient markings is one of several layers of irony. I do not mean irony in a stylistic sense, or that somehow these works lack sincerity. For the literary scholars Robert Scholes and Robert Kellogg irony is a ‘function’ of the fundamental disparity between the various points of view in a narrative: between that of the characters, the narrator, and the audience, and also between the narrator and the author. We know who the characters of A Countervailing Theory are and vaguely who its audience is, but it remains unclear who the narrator and the author are. At the Barbican, the archaeologist’s letter appears at the end, as a conclusion to the display rather than a frame, suggesting that the curator is the narrator. Indeed the immersive drama of the display might have been lessened by the more orthodox curatorial text placed at the start, were it not for the sound that fills the space, composed by Peter Adjaye. This combination of field recordings, synthesisers, African instrumentation and other samples helps instantly transplant the visitor – the audience – to the land of the Eshu and the Koba.

A Forbidden Impulse from A Countervailing Theory (2019), Toyin Ojih Odutola. Courtesy the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York; © Toyin Ojih Odutola

Just over halfway through, I reach Summons; To Witness One’s Own (2019–20): a cluster of male bodies – Koba – shown from the shoulders up, their expressions revealing various degrees of emotional strain as they gather before the supreme leader of the Eshu; at this point in the narrative, an Eshu has been murdered by a rebellious Koba, and the subordinate group must stand before a tribunal. Looking at this work, I have to refer back to the exhibition guide to check the list of materials. Charcoal and pastel on linen over a Dibond aluminium panel, nothing else. I am looking for something to explain the uncanny three-dimensionality of the eyes of the figures in this particular composition. Glinting like the fragments of quartz and calcite found in black shale, these eyes appear to be made of a lustrous mineral with rough, variegated facets. The artist herself describes her process as one in which the surface of the picture is ‘activated’. It turns out that her remark in the archaeologist’s letter that the images are likely made by more than one pair of hands is less ironic than it reads. There is an autonomy to these surfaces. Once activated, they seem to have authored themselves.

‘A Countervailing Theory’ is at the Barbican Art Gallery, London, until 24 January 2021.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home