From the November issue of Apollo: preview and subscribe here

Can you tell me about the Palais de Tokyo exhibition ‘Ugo Rondinone: I Love John Giorno’?

‘I Love John Giorno’ is a kaleidoscopic exhibition about the life and work of American poet John Giorno. It is a solo show by me, Ugo Rondinone, on the subject of Giorno. John and I have been lovers for 18 years. The exhibition is like a love letter, which is why I have called it ‘I love John Giorno’.

The exhibition is divided into eight rooms. The main reason to do the show was John’s archive: I wondered if I could make a visual exhibition about a literature archive, and to challenge it.

There’s a vast amount of archival material on show…

The second room [of eight] is dedicated to John’s archive, which is displayed in two layers – on the wall are photocopies of every archival document starting from 1936, when John was born, right up until 2015: 11,000 documents in total. In the eight rooms there will be 10 tables – each table will have 10 binders for each year: 8o in total (John will be 80 next year). But, this is a translation of the archive, a photo-copied archive. It’s also the story of an Italian immigrant in the US, which will be told through the archive.

Giorno is best known as an avant-garde poet. What is it about Giorno’s work that appeals to you?

For one thing, he is a figure who brings a lot of works together – artwork, poetry work, spiritual work – John has been a Tibetan Buddhist since the early 1970s and this has influenced his work. Since the late ’60s he has also made paintings, or visual poems. Then, at the same time, he is the poster child for a generation that is now vanishing.

Is it important to think about Giorno’s work in relation to the countercultural context of New York in the 1960s?

John is associated with the Happenings in New York during the early ’60s and with Fluxus, which dealt with music, language and visual art. At that time, poets, artists, and dancers were one community – they were not so divided as they are now. It was a relatively small group in New York who defined what American culture is today. In this sense John is a representative figure of that time: the show is a portrait of him, but also of his time.

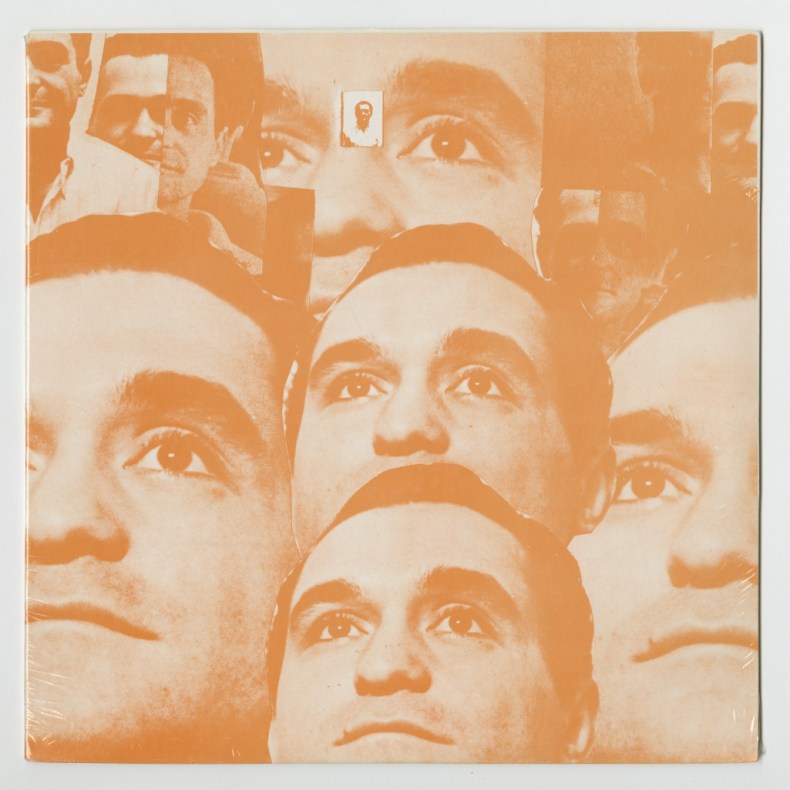

Raspberry LP (front cover artwork) 1967, Giorno Poetry Systems, released by the Intravenous Mind Courtesy Giorno Poetry Systems

Giorno thought of poems as images. Do the intersections between literature and art shape your own work?

They do – many collaborative pieces I have made with John over these 18 years combine two artistic mediums – poetry and art. Contemporary art and poetry shouldn’t be seen as separate, because they have many things in common. But I would specifically say poetry and not literature: poetry doesn’t follow a linear logic like much literature and is in tune with visual art, which is not linear. It is not logical; poetry works very much like dream symbols do.

In what ways can Giorno’s influence be seen in the work of the artists gathered together in this show?

They often use John as a muse. Rirkrit Tiravanija’s work, JG Reads, for example, is a video work showing him reading his complete poetry. In 1998, Pierre Huyghe met John to talk about his experience of making Sleep in 1963 with Andy Warhol – this earlier work is the centerpiece of room three. In Sleeptalking, Huyghe films him like Warhol did, only it’s 35 years later. The two works merge, showing the process of ageing.

John is a person who has touched so many different lives – and not just in the art world, but in the music, poetry, and spiritual worlds.

In 1968 Giorno created Dial-A-Poem, which developed viral strategies for sharing poetry. Do you share his belief in making art more accessible?

Dial-A-Poem was a groundbreaking project – anyone could pick up the phone and listen to a poem. John was a pioneer because he wanted to bring poetry to a bigger audience, to make it popular – this was inspired by Warhol and Pop. Instead of sitting on a table to read a poem, he would take the microphone and perform. From 1965 he was very much part of the sound poetry movement.

Public art should be easily accessible to everyone regardless of people’s background. The symbols I use in my work – the rainbow, the cloud, the stars – are childlike and very basic. I choose childish symbols to facilitate access to art.

This is an exhibition about artistic influence. Who else influences you?

In general my work is influenced by artists, and specifically by German Romanticism. In the early ’90s I made big landscapes when landscapes weren’t so popular. Every symbol in my work – masks, trees, etc. – comes from this tradition.

‘Ugo Rondinone: I Love John Giorno‘ is at the Palais de Tokyo until 10 January 2016

Click here to buy the latest issue of Apollo

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home