We have only about 20 authenticated works by Jan van Eyck, three of which are currently on display at the Kunsthistorisches Museum in ‘Als ich can’. The show takes its title from the painter’s personal motto, which could be translated from the Flemish as ‘As well as I can’, as in ‘I’m doing as well as I can’ or ‘This is as well as I can do.’ It would have been an aristocratic affectation for a late-medieval artist to adopt a motto, but in this and other ways Van Eyck anticipates the artists of the Renaissance: unlike his European contemporaries, he regularly signed his name, maintained his own workshop, accepted private commissions, and even had a second life as a political operative, dispatched on secret missions by Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy, whose service he entered in 1425. If he had written an autobiography, it would have read something like Cellini’s.

Van Eyck’s artistic mantra might as well have been the adage ‘art hides art’. Erwin Panofsky compared the artist’s style to ‘infinitesimal calculus’, a ‘technique so ineffably minute that the number of details comprised by the total form approaches infinity’. He also wrote of Van Eyck’s works exerting ‘a strange fascination not unlike that which we experience when permitting ourselves to be hypnotized by precious stones or when looking into deep water’. The numerous details, almost imperceptible without a magnifying glass, add up to a sum more expressive and alive than its ingenious constituent parts.

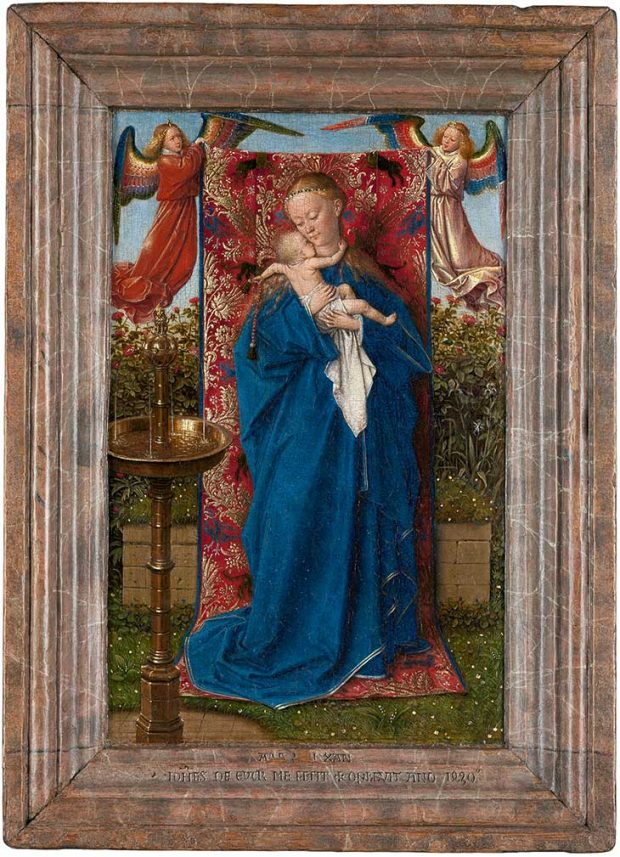

Madonna at the Fountain (1439), Jan van Eyck. Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Antwerp

Take Madonna at the Fountain (1439), the centrepiece of ‘Als ich can’, on loan from Antwerp. This small panel – just 19 by 12.5 centimetres, about the size of a hardcover book – shows a contemplative Virgin Mary, wearing her traditional blue and holding the baby Jesus, who reaches up with one little arm and kisses her neck. They stand in an enclosed garden – the hortus conclusus a symbol of Mary’s virginal integrity. Two angels with rainbow wings hold up a tapestry as a backdrop, creating a half-enclosed space. The panel would have been an object of private devotion, an icon-like image to be held close and studied in moments of prayer and reflection. It is an object for use, one that hews closely to established conventions of portraying the Virgin – almost self-consciously so. But how could even the most attentive viewer notice that reflected on the surface of the fountain, on the egg-like central node from which the dragon-shaped spigots branch out, and on the surface of the basin below, are the outlines of an arched window?

If you look closely, you’ll see that the white rectangles aren’t simply a highlight. They’re the negative of a window, with a strong central beam and an arched top. The reflection is more than just a curious detail; in the late Middle Ages, the passage of light through glass was a metaphor for the conception of Christ – specifically, the way the Holy Ghost penetrated Mary without violating her, just as light travels through the pane of a window.

Madonna and Child (detail; 1439), Jan van Eyck. Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Antwerp

An eagle-eyed and iconographically literate viewer may have noticed the reflection of the arched window, and may have reflected on the Annunciation as part of their devotions. But who would have seen the two small rings on Mary’s right hand? These two gold rings simply cannot be seen without magnification – I’ve tried. So why are they there? One wonders if it is merely a coincidence that on this almost impossibly detailed panel the artist could not resist the opportunity of inscribing his quietly boastful personal motto, itself partially hidden through transliteration into Byzantine Greek letters. The motto is painted on a frame that is in turn painted in such compelling trompe l’oeil style that you have really to scrutinise it to see that it is wood and not veined marble – a kind of transubstantiation achieved through painterly skill. Beneath the motto Van Eyck signed his name: JOH[ann]ES DE EYCK ME FECIT + [com]PLEVIT ANO 1439. ‘Jan van Eyck made me and perfected [me] in the year 1439.’

The inscription would be redundant unless there is something more than picture-making going on in the Madonna at the Fountain. Van Eyck ‘perfects’ the painting as an object of devotion, inscribing secrets that only the most dedicated and knowledgeable viewer would perceive; perhaps that viewer is God, who needs no magnifying glass. Regardless of whether Van Eyck is painting for a human or divine audience, the religious and the painterly ends are one: Madonna at the Fountain is an expression of piety that is also a demonstration of skill. By the end of the 15th century, in Florence, Pico della Mirandola would argue that piety and egotism aren’t necessarily at odds: human beings resemble their God, and should revel in their potentially infinite capacity for thought and creation. ‘Als ich can’ begins to sound a bit less like a captatio benevolentiae and a bit more like a statement of false modesty.

The Goldsmith Jan de Leeuw (1436), Jan van Eyck. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

The two other pieces in ‘Als ich can’ are secular portraits from the Kunsthistorisches’ own collection. The more accomplished of the two shows the goldsmith Jan de Leeuw (1436). The almost photorealistic face of the goldsmith looms large in the folio-sized image: too big for the body it belongs to, and much brighter than the dark tones of the man’s clothing and the deep blue background. One almost expects de Leeuw to start breathing and blinking. Van Eyck’s infinitesimal calculus is at work here in the man’s subtle five o’clock shadow, each hair follicle individually painted (presumably with a single-hair brush), and in the slight redness at the corner of his eyes.

The identity of the sitter in the other work (c. 1438) is uncertain; he was once thought to be the Cardinal Albergati. Although the painting is not quite as fine (Panofsky thought that it was painted from a drawing, without reference to the living subject), and it has undergone somewhat violent cleaning, it is animated by the same qualities. The face of the kindly old man, vivid against the turquoise blue of the backdrop, sprouts with faintly visible white stubble. Fleshy wrinkles crease the old man’s face, a memento mori in contrast to the vigorous health of the younger goldsmith.

Portrait of a scholar (c. 1435), Jan van Eyck. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

‘Als ich can’ includes several other paintings: a small altarpiece by Hans Memling, a diptych by Hugo van der Goes, a portrait of a goldsmith by Gerard David (featured in a 17th-century painting of a Wunderkammer by Frans Francken, which hangs alongside). All of these pieces have at one point or another been attributed to Van Eyck, but all except the Memling pale in comparison. On display, too, is a sumptuous chasuble, worn by members of Philip the Good’s Order of the Golden Fleece, as well as an unusual prayer book, illuminated with a portrait of Philip and attached to a small diptych: a portable devotional unit. These objects are intended to show how van Eyck’s painting was closely related to the other media in which he also worked.

In the end, however, it is Van Eyck’s paintings that exert the strongest pull. The Virgin’s subtle smile, the cardinal’s creased temples, the goldsmith’s bloodshot eyes still staring with acute attention after nearly 600 years – with these little touches Van Eyck performs his painterly alchemy.

‘Als ich can’ is at the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, until 20 October.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home