‘One would think,’ wrote Thomas Gray in 1762 after visiting Hardwick Hall in Derbyshire, ‘Mary, Queen of Scots, was but just walk’d down into the Park with her Guard for half-an-hour. Her Gallery, her room of audience, her antichamber, with the very canopies, chair of state, footstool, Lit-de-repos, Oratory, carpets, & hangings, just as she left them, a little tatter’d indeed, but the more venerable; & all preserved with religious care, & paper’d up in winter.’ A few years later, the gothic novelist Ann Radcliffe stood on the same spot and found herself ‘not without emotion’ as she pictured Mary’s ‘proud yet gentle and melancholy look, as, led by my Lord Keeper, she passed slowly up the hall’. Their accounts are intensely atmospheric – I can almost see her there myself – but the awkward fact remains that Mary had not been imprisoned at Hardwick, but, among other places, at nearby Chatsworth. After Chatsworth was remodelled in the late 17th century there was little left to connect her with it; there was no question, though, that the great Elizabethan prodigy house Hardwick looked the part, even if it was built after her execution.

Queen Victoria and Prince Albert at the Bal Costumé of 12 May 1842 (1842–46), Sir Edwin Landseer. Royal Collection Trust/© HM Queen Elizabeth II 2020

These were the years in which Britain fell in love with its past. And although this passion had its cerebral aspects, its lifeblood was chiefly composed of emotion and imagination. Many felt the desire to climb inside history – to do more than merely visit the scenes of past events – and one way to do this was to re-enact bygone traditions. It was time to reach for the dressing-up box; and no-one did this more whole-heartedly than Archibald Montgomerie, 13th Earl of Eglinton. In 1839 he staged a medieval-style tournament at his castle in Ayrshire with jousting and competitions for which his guests wore historical costumes, he a spectacular suit of gold armour. Sadly the Scottish weather failed to smile on this outbreak of medievalism, but even heavy rain did nothing to dampen a passion for the olden days which thrived over the following decades. Just three years after the Eglinton Tournament, Queen Victoria and Prince Albert held an extravagant bal costumé at Buckingham Palace, for which they dressed as Edward III and his consort Queen Philippa of Hainault, their costumes based on tomb effigies at Westminster Abbey (although, as Landseer’s double portrait reveals, the queen was not prepared to relinquish her fashionable corseted shape). Subsequent costume balls evoked, respectively, the early Georgian and Restoration eras. History, it seemed, had to be animated: when Joseph Nash compiled his four-volume Mansions of England in the Olden Time between 1839 and 1849, he livened up his meticulously detailed interior views of country houses with tableaux of figures dressed in Tudor or Stuart costume, drinking ale in the parlour and playing skittles in the long gallery.

And When Did You Last See Your Father (1878), William Frederick Yeames. Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool

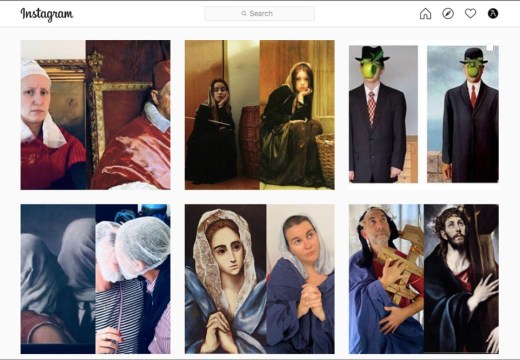

Artists specialising in historical genre pictures recreated the past in subtler ways. While there was a long tradition of painting particular historic events, the St John’s Wood Clique (formed in the early 1860s) specialised in conjuring up imaginary situations from the interstices of history’s hard data, particularly that of the Tudor and Stuart periods. Among the most successful of these fictions was William Frederick Yeames’s And When Did You Last See Your Father (1878), a tense scene set during the English Civil War in which a small boy, the son of a Royalist, is interviewed by Parliamentarians – the painting was, in fact, so wildly popular that it was eventually recreated as a waxwork tableau for Madame Tussaud’s. This was an accolade awarded to few paintings; but many photographers paid tribute to works of art by reinterpreting them. Lewis Carroll photographed Kate Terry in a pose recalling Rembrandt’s Andromeda Chained to the Rocks (though copiously clothed), while Oscar Rejlander reinterpreted Sassoferrato’s The Virgin in Prayer. While oil painting had long been a self-referential echo-chamber, the same motifs, poses and subjects reappearing over the course of centuries, there can be something unsettling about mid 19th-century photographers ‘doing’ the Old Masters. The medium of photography exposes an inherent instability in this hall of mirrors that usually goes unremarked, and uncovers layers of play-acting, of parody, of tableau vivant-ery.

‘The Virgin in Prayer’ (c. 1857), Oscar Gustav Rejlander. National Portrait Gallery, London. Image used under Creative Commons licence (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0)

The tableau vivant was perhaps the 19th-century’s fondest love-letter to the olden times. Beginning as staged representations of well-known paintings, often shown in public theatres, tableaux were quickly adopted by the aristocracy as private evening entertainments – taking part in one required little acting skill, and lavish costumes in which to show off were de rigueur. The staging of historical scenes became increasingly popular – Mary, Queen of Scots, was frequently impersonated – and the historical novels of Sir Walter Scott provided a particularly rich source of subjects. In the early 1830s David Wilkie found himself designing a grand series of tableaux based on Scott’s novels for the Marchioness of Salisbury at Hatfield, for which a number of preparatory sketches survive – what had begun as an imitative art had become an original one. Tableaux vivants were even among the amusements staged for Queen Victoria. Photographs by Charles Albert Wilson record the royal family and household enacting episodes from the life of Bonnie Prince Charlie, from Romeo and Juliet, from Thomson’s Seasons. One winter’s day at Balmoral – a castle built in the 1850s in the Scottish baronial style – it was the turn of Scott’s Ivanhoe (1819), a novel set in 12th-century England. Anyone wishing to illustrate the phenomenon of Victorian historicism could do worse than start there.

Inventing the past could, however, lead to the past inventing you. It is arguably on account of Scott, whose romanticised reimaginings of Scottish history and landscape Victoria and Albert both read voraciously as children, that they bought the Balmoral estate in the first place.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home