The Wallace Collection is famously Vivienne Westwood’s favourite art gallery and it’s not hard to see why; the townhouse-turned-museum in Manchester Square is full of high drama and meticulous craftsmanship. The fashion designer has called it ‘the greatest art school in this country’, claiming with typical bombast that ‘nobody today could make one thing that’s in there, nobody… could paint even one little flower on the Sèvres porcelain.’

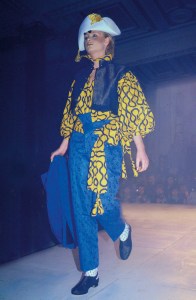

‘Pirate’. Photo: Niall McInerney; © Bloomsbury Publishing plc

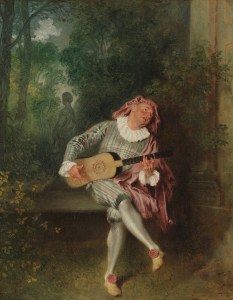

Mezzetin (c. 1718–20), Jean-Antoine Watteau. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The mother of punk is an art lover who has referred to all kinds of artists in her collections – Van Eyck, Velázquez, Rubens, Matisse, Frida Kahlo, Keith Haring – and many of her signature garments and patterns can be traced back to the paintings from which she has liberated them. Delicately shredded denim finds its roots in 16th century-portraits featuring slashed doublets; bright geometric prints are inspired by Watteau’s paintings of harlequins (and an evening gown of 1996 is simply named after the painter).

Westwood has shown a particular affinity with the 18th century, rifling through the works of rococo painters for their costumes, colours and ironies and symbolic resonances. As Alexander Fury observes in the introduction to Vivienne Westwood Catwalk: The Complete Collections (Thames & Hudson), Westwood has a puckish predilection for ‘dust[ing] the cobwebs off history’. In the case of art, what has often been revealed beneath is a ‘bubbling licentiousness […] the titillation of the Rococo paintings of Boucher and Fragonard […] the innate sensuality of ancient Greco-Roman drapery’.

Boucher’s Daphnis and Chloe of 1743–45 (also known as Shepherd Watching a Sleeping Shepherdess) is a great example of this tongue-in-cheek titillation. Heavy on pastoral eroticism – the woman bare-breasted and blushing with slumber while her paramour leans over, eyes drifting towards her nipples – the painting hangs in the Wallace Collection. The pair first turned up on a series of corsets in her Autumn-Winter 1990 collection ‘Portrait’. Westwood had already been toying with the riches and hypocrisies of the art world, decking out her models in fig leaves and materials reminiscent of neoclassical statues, but this marked the first time that she reproduced oil paintings directly on fabric. It was also the first collection to which her now-husband Andreas Kronthaler contributed (in 2016 Westwood acknowledged the closeness of their collaboration by renaming her Gold Label line ‘Andreas Kronthaler for Vivienne Westwood’).

Daphnis and Chloe (1743), François Boucher. The Wallace Collection, London.

Corset from Vivienne Westwood’s ‘Portrait’ collection of 1990, with François Boucher’s Daphnis and Chloe printed on the front panel. Victoria and Albert Museum, London

A modern take on stays, complete with a zipper and lycra panels, the corsets are extremely bodily. The style is known as ‘the Stature of Liberty’ and is designed to cantilever and squash the wearer’s breasts, making them as voluptuous as one of those rococo paintings. They were originally styled on the catwalk with tasselled shorts and strings of pearls. Today’s wearers, who include FKA Twigs and Rowan Blanchard (as well as Bella Hadid, who was pictured in 2019 wearing a corset featuring another Boucher painting Hercules and Omphale), accessorise them with cowboy hats and baggy trousers – embodying the current vogue for a sartorial collaging of past and present.

In fact, collage is a useful way of thinking about Westwood’s forays into the art world. A painting might yield some minute detail of ancien régime costuming to copy, a silhouette to update (over the years these have involved crinolines, bustles, peignoirs, and tailcoats, alongside her famous corsets), a background pattern to turn into a textile, or a generalised mood to use as the basis for the story of a new collection. Dozing Renaissance nymphs inspire feathered eyelashes so long the models look half-asleep. Tudor and Jacobean portraits yield square necklines with stiff collars and an air of queenly grandeur.

It’s the kind of grabby approach to the visual world that appeals to the magpie-minded among us. No doubt it’s what led me as a teenager to stick postcards of Elizabeth I and Ingres’s Portrait of Madame Moitessier in a scrapbook, using them as the basis for my own crude fashion sketches: drawing pearled shoes with little ruffs around the ankles, and carefully enlarging Moitessier’s tassels and florals to gargantuan proportions. It’s an approach that offers the promise of fashion as both a story and as an uncomplicated arena where one can mix together histories, aesthetics and cultural artefacts with abandon.

Of course, one can’t just sweep through history with a swag bag over one shoulder. Westwood has come under fire for various inspirations; as with many other designers, there’s an uncomfortable number of references to ‘tribes’, ‘savages’ and non-specified ‘ethnic tailoring’ among her earlier works – and the 2010 collection inadvertently echoing Zoolander in its luxe image of homelessness was a real low point. She also embodies the kind of blunt, devil-may-care position in British public life that leads some to herald her as both icon and iconoclast – the kind who accepts her OBE from the Queen, but does so knickerless – and others find infuriating.

Rendez-vous de chasse (c. 1717–18), Jean-Antoine Watteau. The Wallace Collection, London

However, it’s apparent from flicking through the pages of Vivienne Westwood: Catwalk that, for all of her contradictions and challenges, the designer is a genius. The clothes are extraordinary: daring, gorgeous, genuinely provocative. Intelligently contextualised by Fury’s texts about the collections, the photos reveal the meeting point between unbridled imagination and technical flair. These are clothes that shape and subtly change the wearer, marrying fashion’s elusive promise of transformation with garments that actually pay attention to the body. Many of them bring works of art to life with real wit and beauty.

It is therefore unsurprising to see Daphnis and Chloe featuring as a major motif in Westwood’s Autumn-Winter 2021 collection. This time the pair are splashed over jeans and jackets, limbs akimbo on stretch dresses and bowed heads once again supporting plumped up décolletage. A fan might call it vintage Westwood. A cynic might say that the brand’s designs were more engaging when repeated references to an artwork represented the refining of an idea rather than a cashing in on an old notion.

‘Vivienne Westwood Catwalk: The Complete Collections’ is published by Thames & Hudson.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home