The talented William Merritt Chase, born in Williamsburg, Indiana, in 1849, set his sights on a painting career at an early age. This mid-western American boy was a product of his time, immersing himself in international art movements at the fin-de-siècle that rejected the past and embraced the new. As the current retrospective at The Phillips Collection (America’s first museum of modern art), reveals, he established himself as a keen observer of contemporary life, experimented with techniques and media, and assured his legacy as an influential teacher.

To strive to be modern, as Chase’s generation did, was to be party to an evolution in painting that was reductivist in matters of form and content, prefiguring the more radical fracturing and ultimate dissolution of form (through cubism and abstraction) that ensued in the 20th century.

Spring Flowers (Peonies) (1889), William Merritt Chase. Terra Foundation for American Art

In Chase’s prime, Paris was the hub of the international avant-garde, attracting artists from all over the world in search of the new. It was an era of rebellion against outdated dogma, not just in Paris with the founding of the Société nationale des beaux-arts, but with secessionist movements in Brussels, Munich, Berlin and Vienna – and even in New York, whose progressive Society of American Artists Chase helped to found in 1877.

The Young Orphan (c. 1884), William Merritt Chase. National Academy Museum, New York

Chase’s nascent talent was apparent early on. In 1867 he was sent to train with a local Indiana painters, and in 1869 he moved to New York City where he enrolled at the staid National Academy of Design. While he was in St Louis in 1871 (his parents had relocated there), a group of businessmen raised funds so that he could visit Europe. Chase was one of the post-centennial generation of Americans who recognised that it was in their best interests to go abroad: having done so, they could reap the benefits of a foreign education back at home. Chase trained longer than most at the Munich Royal Academy, came under the influence of the Leibl circle, and in 1874 entered the studio of the innovative professor of painting, Karl von Piloty. Realising the talent of this American student, Piloty predicted that the future of art was in America.

In 1878, Chase returned home to teach at the Art Students League where he espoused Piloty’s tenebrist palette and virtuoso brushwork. He also taught respect for the Old Masters, Frans Hals, Anthony van Dyck and Diego Velázquez.

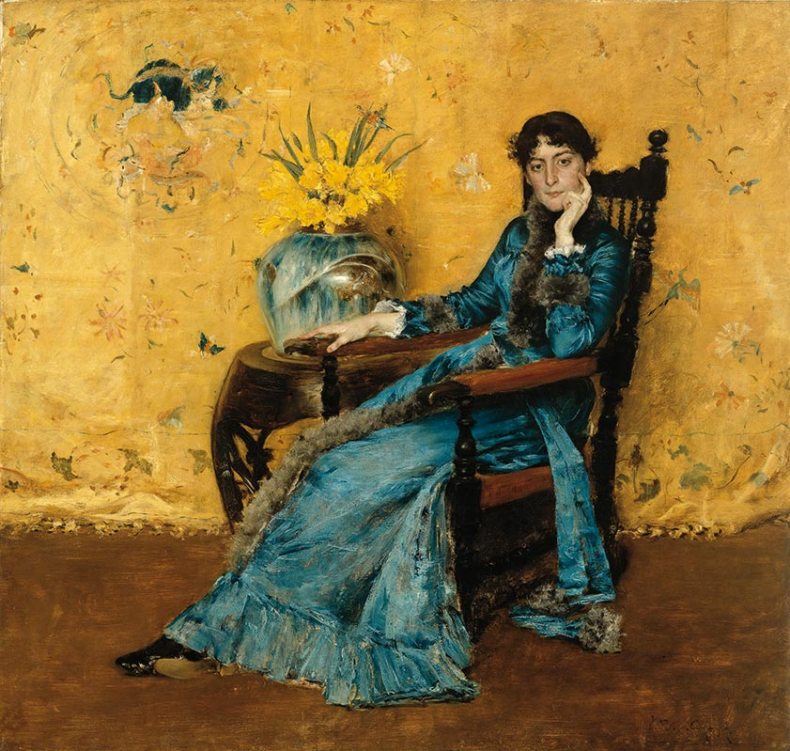

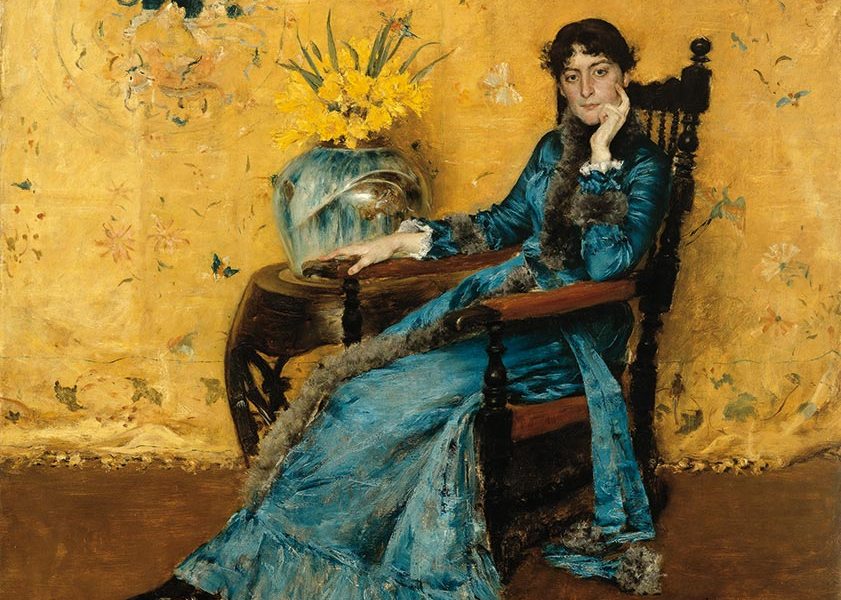

Chase found his stride with his Portrait of Dora Wheeler (1882–83), a winning example of the modern spirit that combines symbolism, tonalism and impressionism. His European reputation rested on this painting, which was exhibited in 1883, both in Paris and in the Munich Crystal Palace where it was awarded a gold medal.

Portrait of Dora Wheeler (1882–83), William Merritt Chase. The Cleveland Museum of Art

After a trip to Holland in 1883 and 1884, Chase’s palette took on an impressionist hue as he tried painting en plein air and investigating the varying effects of light. The works from this period prefigure his light-filled Shinnecock, Long Island landscapes of his mature years. Chase also painted intimate scenes of domesticity, populated by his growing family, that were also orchestrations of form, colour and space.

Velázquez, who Chase called the most modern of the Old Masters, was a constant source of inspiration. In successive summers in the 1880s, in 1896 after he quit teaching at the Art Students League, and again in the new century, he travelled to Madrid to copy the master’s work in the Prado. A painter’s painter, Velázquez’s reduction of form and content, austere and uncluttered spaces blocked out on the vertical, horizontal and orthogonal, were appropriated in Chase’s time by the likes of Carolus-Duran, Leon Bonat, Sargent, and Whistler, to name a few. Hide and Seek, which is owned by The Phillips Collection, is Chase’s own homage to Las Meninas.

Hide and Seek (1888), William Merritt Chase. The Phillips Collection, Washington, DC

This study of one artist’s search for the modern – a path shared by those of his generation on both sides of the Atlantic – advances our understanding not just of Chase’s work, but also of the origins of 20th-century modernism.

‘William Merritt Chase: A Modern Master’ is co-organised by the Phillips Collection, Washington D.C. (where it is on display until 11 September), the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (9 October–16 January 2017), the Fondazione Musei Civici Venezia (10 February–28 May 2017) and the Terra Foundation for American Art.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home