After a bizarre authenticity court case, a Chicago court has ruled that a 40-year-old landscape painting is not by the Scottish-born artist Peter Doig. Retired corrections officer Robert Fletcher brought the lawsuit against the artist in 2013, claiming that Doig had sold the picture to him in the 1970s, and that Doig’s subsequent denials of his account were false. The artist’s lawyers argued that the painting was the creation of another man, Pete Doige, who had been incarcerated at the Thunder Bay correctional centre where Fletcher worked over the period in question. Doige died in 2012, but his family testified in court that the work was his.

‘I feel a living artist should be the one who gets to say yea or nay and not be taken to task and forced to go back 40 years in time,’ said Doig at the ruling. He may have a point, but artists aren’t always completely honest when it comes to authorship…

Lucian Freud

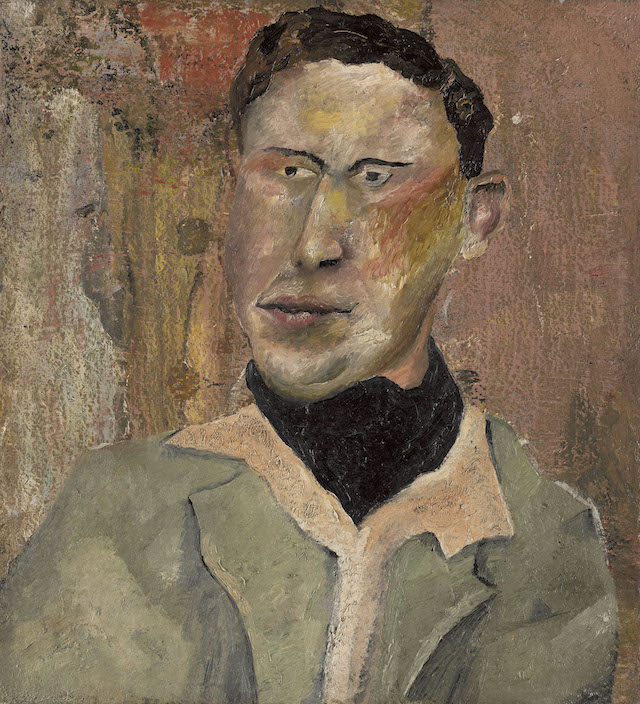

In July 2016, the BBC programme Fake or Fortune? argued that a work which Lucian Freud had long refused to acknowledge was by the artist after all. Freud’s rejection of The Man In a Black Cravat seems to have stemmed from his long-running feud with the artist Denis Wirth-Miller, a former classmate who claimed he found the painting during the Second World War, and wanted to sell it.

Freud publicly rejected the work throughout his life, thwarting Wirth-Miller’s attempts. The current owner, Jon Turner, claims that Wirth-Miller (who died in 2001) gave him the painting in 1997 with the instruction to sell it as publicly as possible to humiliate the artist.

When Fiona Bruce and art historian Philip Mould spoke to Freud’s former solicitor for Fake or Fortune?, the story was complicated again. The solicitor found a note in her files from a phone conversation with Freud in 2006, in which he admitted to starting the painting, but claimed someone else had completed it. Further analysis of the object itself suggested that it was by a single hand, and a panel of three experts invited to assess the work also attributed the portrait to Freud. With the new information, Mould valued The Man In a Black Cravat at £300,000.

Man in a Black Cravat, Lucian Freud. Courtesy BBC

Pablo Picasso

When Picasso was shown a photograph of Erotic Scene (La Douceur) (1903) in the 1960s, he denied he painted it, describing it as a ‘bad joke by friends’. Bequeathed to the Met in 1982, it languished in storage until preparations were underway for the 2010 exhibition ‘Picasso in The Metropolitan Museum of Art’, which featured every single painting, drawing, sculpture and ceramic work by the artist in the collection.

The Met needed to get to the bottom of Erotic Scene’s authorship. Its conservation department determined that its materials were consistent with other works from Picasso’s Blue Period, and new archival research suggested that it was one of two paintings bought in 1912 by Picasso’s dealer Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler from Benet Soler, a tailor whose shop the artist frequented. Attribution affirmed, the painting made its debut on the Met’s walls.

‘We haven’t shown the painting [before] not because of its subject matter or because of questions of its authenticity, but because it’s not very good’, said Gary Tinterow – then the Met’s curator of 19th-century, modern and contemporary art – in the run-up to the exhibition. Presumably Picasso agreed, which may explain why he wasn’t too keen for its true authorship to be known.

Cady Noland

Other artists have disowned their work instead of rejecting it outright. When Ohio collector Scott Mueller bought Cady Noland’s Log Cabin Blank With Screw Eyes and Café Door (1990) from Galerie Michael Janssen in July 2013, he mentioned to the sculptor that he was planning to restore parts of it. Exactly when he did so is unclear, but some of the work’s wooden elements were indeed replaced. Noland, in response, sent him an angry handwritten note stating, ‘This is not an artwork’ and objecting to how it was ‘repaired by a consevator [sic] BUT THE ARTIST WASN’T CONSULTED’. She also demanded that the piece come with a notice explaining that it was unapproved. In June 2015, Mueller filed a lawsuit to reverse his purchase, which had cost him £1.4m, on the grounds that his sale contract with Janssen stated that the gallerist would buy back the work if Noland ‘affirmatively refuses to acknowledge or approve the [work’s] legitimacy’.

A similar incident occurred in November 2011, when the artist disavowed her aluminium print Cowboys Milking (1990) on the eve of an auction at Sotheby’s. Noland complained that the work was damaged, and that ‘her honor and reputation [would] be prejudiced as a result of offering [it] for sale with her name associated with it’, so Sotheby’s withdrew it. The owner, art dealer Marc Jancou, went to court, seeking $26 million in damages from Sotheby’s and Noland – but both cases were dismissed.

Gerhard Richter

In July 2015, Artnet News reported that Gerhard Richter no longer acknowledges works from his early West German period as his. Between 1962 and 1968 the painter was experimenting with a realistic, figurative painting style that is quite different from his later abstract and photo-realist paintings. Richter, who keeps strict control of his catalogue raisonné, seemingly disliked his work from this period enough to want to strike it from his oeuvre.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home