In light of recent announcements of additional investment in the Northern Powerhouse and the forthcoming departure of Maria Balshaw from Manchester Art Galleries and the Whitworth to take up her new role at Tate, now is an ideal time to reflect on cultural spending and leadership in the north of England.

Balshaw’s success is largely a result of her strategic vision for Manchester’s major visual arts institutions. The impact of her leadership on this sector should not be underestimated, and it will be sorely missed by the city. At the very least, it culminated in the Whitworth being designated the Art Fund Museum of the Year in 2015. In her capacity as director of culture for Manchester, Balshaw acted as a close advisor to the chief executive of Manchester City Council and principal negotiator across a range of senior stakeholders and networks. In this role as the de facto cultural tsar of Manchester, Balshaw enjoyed ready access to George Osborne and also oversaw negotiations over the contentious Factory.

Perhaps a legacy of this privileged access, the north-west was by far the biggest winner in Theresa May’s northern giveaway last week, with Greater Manchester receiving over £130m, followed by Liverpool city region’s £72m. Despite its population of 3 million (compared with Greater Manchester’s 2.6 million), the Leeds city region was only awarded £67.5m, sparking comments of a looming east-west divide in government investment in the North. This additional funding for Manchester should be viewed in the context of recent cultural investment, which saw £78m awarded to fund the redevelopment of The Factory, alongside £5m ACE funding allocated to Manchester’s new multi-arts centre HOME in April 2015, plus a £15m refurbishment of Balshaw’s Whitworth. So I make that a cool £228m for Manchester in the past few years, over and above the core revenue funding it receives for its preponderance of existing arts venues.

The Whitworth was awarded the Art Fund Museum of the Year Award in 2015 following a major renovation project overseen by Maria Balshaw, who moves this year to lead the Tate.

Thus far, Manchester has reacted quickly and aggressively to the opportunities offered by the Northern Powerhouse, and it has been accordingly rewarded. The Factory will provide a permanent home for the biennial Manchester International Festival and house a new Skills Academy. Revenue funding of £9m has also been promised by central government, but this will need to be bankrolled by Arts Council England. It is worth noting here that this earmarked funding completely bypassed existing policy frameworks for capital funding; and if its NPO bid is successful, The Factory would become the sixth biggest NPO in England, hoovering-up potential funds from smaller NPOs and regions, and very possibly cannibalising the already stretched artistic provision in the north-west. Although HOME is producing and programming some ground-breaking work and seemingly confounding predictions that it will struggle to build an audience (largely thanks to a disproportionate number of ‘experience seekers’ and ‘metroculturals’ compared with the Greater Manchester region), there are real concerns that the Manchester market is becoming saturated. This was flagged up in a recent report on The Factory by The Audience Agency, which also highlighted the significant risks of market competition.

From my own conversations and interviews with cultural and civic leaders in the North, it seems that the current emphasis is very much on collaboration. Despite a high (and seemingly justifiable) degree of cynicism to the east of the Pennines, cities such as Leeds acknowledge that the Northern Powerhouse has the potential to ‘warm-up’ relationships and encourage policymakers to be ‘less fearful of radical new models’. It could also provide a backdrop to make some savings between northern authorities in terms of cultural provision. The implications for cultural leadership are therefore that a more collaborative and relational approach will most likely yield the greatest dividends.

Last week, the government also announced an ‘early sector’ deal with the creative industries as part of its shiny new industrial strategy. A stated aim of this strategy is to spread growth and prosperity more evenly around the country. This seems to me to suggest an implicit commitment to further devolution – branded largely through the Northern Powerhouse initiative established in June 2014 in a speech (delivered in Manchester) by George Osborne. The sporadic inclusion of the arts and culture within the Northern Powerhouse raises questions about conflicting policy approaches, for example between capital and revenue investment, between the seeming obsession to build new arts venues rather than fund wider access to the arts for local people. Let’s not forget that Arts Council England’s mission remains to fund great art and culture for everyone!

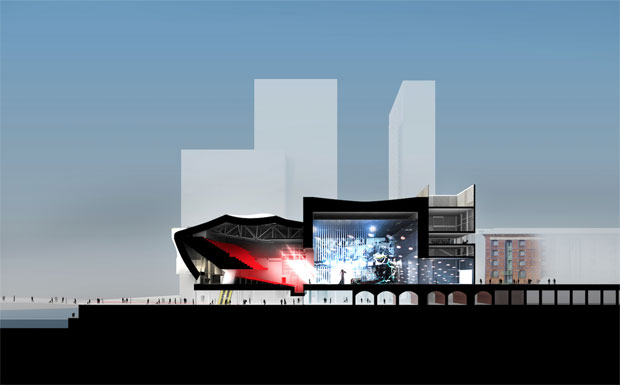

The Factory will eventually provide a permanent home for the biennial Manchester International Festival. © OMA. Image Courtesy Factory Manchester

This mission is not looking remotely credible in an era where local authorities are increasingly struggling to fund even statutory obligations such as social care, and where arts funding is quite literally becoming a lottery (and one that is funded through regressive taxation). A recent Countries of Culture Select Committee report highlighted how arts funding tends to be self-generating. This implies that places currently suffering from a disproportionately low provision of funded culture (i.e. many peripheral towns and rural areas in the North) will fall even further behind. In the meantime, small arts venues and community arts projects risk obsolescence as funding is redirected away from the interests of local people and places towards large cultural vanity projects.

The recent parliamentary enquiry into arts funding culminated in ACE being instructed to redistribute funds away from London. This so-called ‘rebalancing’ of Lottery funding towards the regions, coupled with additional Northern Powerhouse funding, is likely to ease the north-south divide, at least in terms of capital investment in cultural infrastructure. But in order to avoid a damaging east-west divide, Balshaw’s replacement as one of the most powerful cultural leaders in northern England will need to look well beyond Greater Manchester and engage with colleagues across the North. At the same time, she or he will need to engage strategically at a national level – but perhaps even more importantly at a granular, grassroots level, in order to ensure that any uplift in funding trickles down to artists and local communities. Balshaw recently declared that her aim for Manchester was to engender cultural democracy. Let’s just hope that her replacement places this goal at the top of what will certainly be a very heavy in-tray.

Dr Ben Walmsley is Associate Professor in Audience Engagement in the School of Performance and Cultural Industries at the University of Leeds. He would like to thank Dr Abigail Gilmore, University of Manchester, for her invaluable input into this article.

Will Manchester’s cultural boom benefit the whole of the North?

Manchester's Factory arts centre, designed by Rem Koolhaas's OMA practice, was granted planning permission in January and has received significant funding from the UK government. © OMA. Image Courtesy Factory Manchester

Share

In light of recent announcements of additional investment in the Northern Powerhouse and the forthcoming departure of Maria Balshaw from Manchester Art Galleries and the Whitworth to take up her new role at Tate, now is an ideal time to reflect on cultural spending and leadership in the north of England.

Balshaw’s success is largely a result of her strategic vision for Manchester’s major visual arts institutions. The impact of her leadership on this sector should not be underestimated, and it will be sorely missed by the city. At the very least, it culminated in the Whitworth being designated the Art Fund Museum of the Year in 2015. In her capacity as director of culture for Manchester, Balshaw acted as a close advisor to the chief executive of Manchester City Council and principal negotiator across a range of senior stakeholders and networks. In this role as the de facto cultural tsar of Manchester, Balshaw enjoyed ready access to George Osborne and also oversaw negotiations over the contentious Factory.

Perhaps a legacy of this privileged access, the north-west was by far the biggest winner in Theresa May’s northern giveaway last week, with Greater Manchester receiving over £130m, followed by Liverpool city region’s £72m. Despite its population of 3 million (compared with Greater Manchester’s 2.6 million), the Leeds city region was only awarded £67.5m, sparking comments of a looming east-west divide in government investment in the North. This additional funding for Manchester should be viewed in the context of recent cultural investment, which saw £78m awarded to fund the redevelopment of The Factory, alongside £5m ACE funding allocated to Manchester’s new multi-arts centre HOME in April 2015, plus a £15m refurbishment of Balshaw’s Whitworth. So I make that a cool £228m for Manchester in the past few years, over and above the core revenue funding it receives for its preponderance of existing arts venues.

The Whitworth was awarded the Art Fund Museum of the Year Award in 2015 following a major renovation project overseen by Maria Balshaw, who moves this year to lead the Tate.

Thus far, Manchester has reacted quickly and aggressively to the opportunities offered by the Northern Powerhouse, and it has been accordingly rewarded. The Factory will provide a permanent home for the biennial Manchester International Festival and house a new Skills Academy. Revenue funding of £9m has also been promised by central government, but this will need to be bankrolled by Arts Council England. It is worth noting here that this earmarked funding completely bypassed existing policy frameworks for capital funding; and if its NPO bid is successful, The Factory would become the sixth biggest NPO in England, hoovering-up potential funds from smaller NPOs and regions, and very possibly cannibalising the already stretched artistic provision in the north-west. Although HOME is producing and programming some ground-breaking work and seemingly confounding predictions that it will struggle to build an audience (largely thanks to a disproportionate number of ‘experience seekers’ and ‘metroculturals’ compared with the Greater Manchester region), there are real concerns that the Manchester market is becoming saturated. This was flagged up in a recent report on The Factory by The Audience Agency, which also highlighted the significant risks of market competition.

From my own conversations and interviews with cultural and civic leaders in the North, it seems that the current emphasis is very much on collaboration. Despite a high (and seemingly justifiable) degree of cynicism to the east of the Pennines, cities such as Leeds acknowledge that the Northern Powerhouse has the potential to ‘warm-up’ relationships and encourage policymakers to be ‘less fearful of radical new models’. It could also provide a backdrop to make some savings between northern authorities in terms of cultural provision. The implications for cultural leadership are therefore that a more collaborative and relational approach will most likely yield the greatest dividends.

Last week, the government also announced an ‘early sector’ deal with the creative industries as part of its shiny new industrial strategy. A stated aim of this strategy is to spread growth and prosperity more evenly around the country. This seems to me to suggest an implicit commitment to further devolution – branded largely through the Northern Powerhouse initiative established in June 2014 in a speech (delivered in Manchester) by George Osborne. The sporadic inclusion of the arts and culture within the Northern Powerhouse raises questions about conflicting policy approaches, for example between capital and revenue investment, between the seeming obsession to build new arts venues rather than fund wider access to the arts for local people. Let’s not forget that Arts Council England’s mission remains to fund great art and culture for everyone!

The Factory will eventually provide a permanent home for the biennial Manchester International Festival. © OMA. Image Courtesy Factory Manchester

This mission is not looking remotely credible in an era where local authorities are increasingly struggling to fund even statutory obligations such as social care, and where arts funding is quite literally becoming a lottery (and one that is funded through regressive taxation). A recent Countries of Culture Select Committee report highlighted how arts funding tends to be self-generating. This implies that places currently suffering from a disproportionately low provision of funded culture (i.e. many peripheral towns and rural areas in the North) will fall even further behind. In the meantime, small arts venues and community arts projects risk obsolescence as funding is redirected away from the interests of local people and places towards large cultural vanity projects.

The recent parliamentary enquiry into arts funding culminated in ACE being instructed to redistribute funds away from London. This so-called ‘rebalancing’ of Lottery funding towards the regions, coupled with additional Northern Powerhouse funding, is likely to ease the north-south divide, at least in terms of capital investment in cultural infrastructure. But in order to avoid a damaging east-west divide, Balshaw’s replacement as one of the most powerful cultural leaders in northern England will need to look well beyond Greater Manchester and engage with colleagues across the North. At the same time, she or he will need to engage strategically at a national level – but perhaps even more importantly at a granular, grassroots level, in order to ensure that any uplift in funding trickles down to artists and local communities. Balshaw recently declared that her aim for Manchester was to engender cultural democracy. Let’s just hope that her replacement places this goal at the top of what will certainly be a very heavy in-tray.

Dr Ben Walmsley is Associate Professor in Audience Engagement in the School of Performance and Cultural Industries at the University of Leeds. He would like to thank Dr Abigail Gilmore, University of Manchester, for her invaluable input into this article.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

Share

Recommended for you

Regional museums are opportunities, not burdens – but only if we think creatively

Funding is difficult, but local councils must wake up to the potential of the art and museums in their care, and fight to secure their future

How to stop the creative industries running out of steam

The Cultural Learning Alliance has released a report which makes a reasoned case for adding the arts to the STEM subjects. Will the government take note?

Personality of the Year

Maria Balshaw, the director of the Whitworth Art Gallery and Manchester City Galleries, has been a driving force behind the city’s cultural renaissance