In an anonymous satirical poem of 1750, a group of Londoners discuss an engraving hanging in a printseller’s window. One bystander is struck by the equal treatment the artist has given to his two subjects: a man and a dog. Another explains:

Tis Hogarth himself and his Friend […]

Insep’rate Companions! And therefore you see

Cheek by Joul they are drawn in familiar Degree

William Hogarth’s fondness for dogs is well documented – and it is clear to see in Tate Britain’s current exhibition, ‘Hogarth and Europe’, in which human subjects are routinely accompanied by canine companions. His favourite muse was his own dog, Trump, who is accordingly one of the most recognisable dogs in the history of art, and has often been used as a symbol for Hogarth himself since the artist’s own lifetime. Famously, Trump accompanies Hogarth in his self-portrait of 1745, Painter and His Pug (of which the image discussed in the poem is almost certainly an engraving). Or rather, he accompanies Hogarth’s likeness, which appears as a portrait-within-a-portrait. Trump is the true sitter here.

The Painter and his Pug (1745), William Hogarth. Tate, London.

Before his starring role in Painter and His Pug, Trump popped up in a number of other paintings. A commentary on Hogarth’s works published in 1768 identifies the pug that appears in the fifth scene of The Rake’s Progress as ‘Trump, a favourite dog of Mr Hogarth’s’. In The Strode Family, painted around 1738, Colonel Strode’s walking stick draws the viewers’ eye towards the dog; in Captain Lord George Graham in his Cabin (1745), Trump, tongue characteristically lolling out of his mouth, squats on a chair on his hind legs, wearing the captain’s wig and apparently reading a sheet of music. X-rays of Hogarth’s final self-portrait, painted to celebrate his appointment as Sergeant Painter to the King in 1757, show that it originally depicted a pug (perhaps Trump) pissing on pictures piled on the floor. Hogarth evidently thought better of this and painted over it.

Captain Lord George Graham in his Cabin (c. 1745), William Hogarth. Royal Museums Greenwich

Trump was not Hogarth’s first pug; in December 1730, he placed an advert in The Craftsman, offering a reward of half a guinea for the return of ‘a light colour’d Dutch DOG, with a black Muzzle’, named ‘Pugg’. He probably acquired Trump soon after this, in the early 1730s. Generally known as Dutch dogs, or Dutch mastiffs, pugs were closely associated with the Netherlands; Trump’s name, shared with many other pugs, was an anglicisation of Tromp, the name of two famous Dutch admirals of the 17th century.

With his gangly legs and long muzzle, Trump’s appearance is quite different to that of today’s pugs. He was the product of an age before dog shows and breed standards, when pugs came in a wider variety of shapes. But Trump does share something with his 21st-century counterparts; out of step with the fashion at the time, Trump’s ears were not cropped. Hogarth was a committed opponent of animal cruelty, as is evident in The Four Stages of Cruelty (1751), in which urchins gleefully torture street animals, and stressed workers clobber their horses and livestock. These convictions informed his private life too.

The artist’s fondness for his little dog manifested in many ways that were unusual for the time – especially for a man of the ‘middling sort’, like Hogarth, since pugs were the stereotypical pets of the materialistic elite he satirised in his art. After the pair visited a fair held on the frozen Thames in 1740, Hogarth had a souvenir sheet printed with Trump’s name as a memento. The 19th-century painter and collector of Hogarth memorabilia, John Phillip, reported that the dog drank from a ‘marble cistern’ positioned on a stool in front of a bow window.

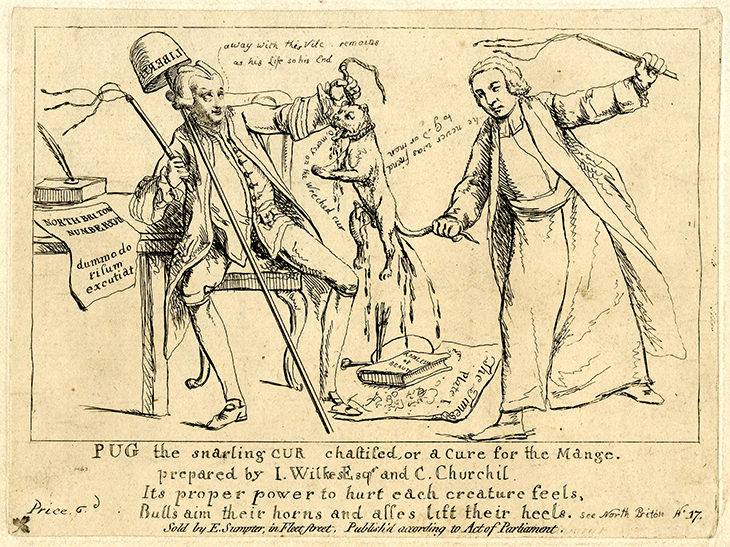

Anonymous satirical print, commissioned by John Wilkes and Charles Churchill in 1763. British Museum, London

Hogarth’s attachment to Trump was seized on by his critics, for whom the figure of the pug could be both a handy stand-in for Hogarth himself and – given the perceived ugliness of these dogs – grounds for calling into question his opinions on aesthetics. In a caricature of 1753, The Burlesquer Burlesqued, Paul Sandby depicts Hogarth as a half-pug monstrosity, while a pug named Jewel passes the artist ‘a bone to pick in the line of beauty’, mocking the theories regarding the ‘serpentine line’ Hogarth had presented in his Analysis of Beauty, published earlier that year. More disturbing is the satirical print commissioned by John Wilkes and Charles Churchill during their feud with the artist in 1763; here, the two flay a pug who represents Hogarth. The anonymous artist revels in the violence meted out to the dog, which begs the tormentors to take ‘mercy on the Wretched cur’. Perhaps Hogarth produced The Bruiser in response to this attack, reworking an engraving of Painter and His Pug to make an angry Trump urinate on a letter by Churchill attacking his owner.

The Bruiser (1763), William Hogarth. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Hogarth scholars still struggle to explain Hogarth’s preference for these dogs. The pug was the dog du jour for fashionable women in George II’s Britain; its foreign, pampered air seems at odds with the carefully crafted image of the honest artisan Hogarth took pains to promote. Perhaps he enjoyed subverting such expectations. Pugs also offer a visual pun on pugnacity, and these comic, clownish dogs were exceptionally suitable vessels for Hogarth’s particular brand of irreverent humour. In his paintings, pugs are generally disruptive – in A House of Cards and The Fountaine Family (both c. 1730) they drag oversized tree branches around and gnaw on wicker baskets. Even when they are static, Hogarth repeatedly draws the viewer’s eye to them, either with their comical expressions, or by having human subjects point towards them. And of course, as with our love for other humans, our love for our animal companions need not always be rational.

‘Hogarth and Europe’ is at Tate Britain, London, until 20 March 2022.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home