Being responsible for an exhibition of Raphael drawings has its daunting moments, given the extent of previous scholarship and the remarkable levels of connoisseurship and documentary research that have characterised Raphael studies. My initial idea for ‘Raphael: The Drawings’ at the Ashmolean Museum (1 June–3 September), which developed in conversation with our exhibition partner, the Albertina in Vienna, and its Italian art curator, Achim Gnann, was to find a new perspective on Raphael: one embracing the fact that drawings are fragmentary, layered works made at a particular historical moment, and also intimate artefacts that still ‘speak’ to viewers today.

This meant shifting the ground from questions of attribution and function towards a consideration of the rhetorical and expressive aspects of drawing in Raphael’s time, and the way in which his drawings have continued to address viewers. Ideas around visual and material eloquence – including not only inventiveness and persuasiveness, but also the embodied intelligence of the artist’s hand – coalesced in a research proposal that I developed with Ben Thomas of the University of Kent, my co-investigator, which received a generous award from the Leverhulme Trust in late 2015.

In selecting drawings for the exhibition, with the Ashmolean’s unrivalled holdings as a starting point, I felt it was important to present a comprehensive view of Raphael’s range and interests in drawing – especially his continuing and versatile use of metalpoint – but also to highlight his extraordinary powers of invention, orchestration and expression. Rather than trying to reconstruct entire sequences of studies for particular projects, I wanted to present sheets that show the artist testing and brainstorming; or charging his studies with graphic energy so as to give narrative dynamism to figure groupings; or reflecting, often through elaborate studies of facial features, gestures and drapery, on the passions and motivations of his protagonists.

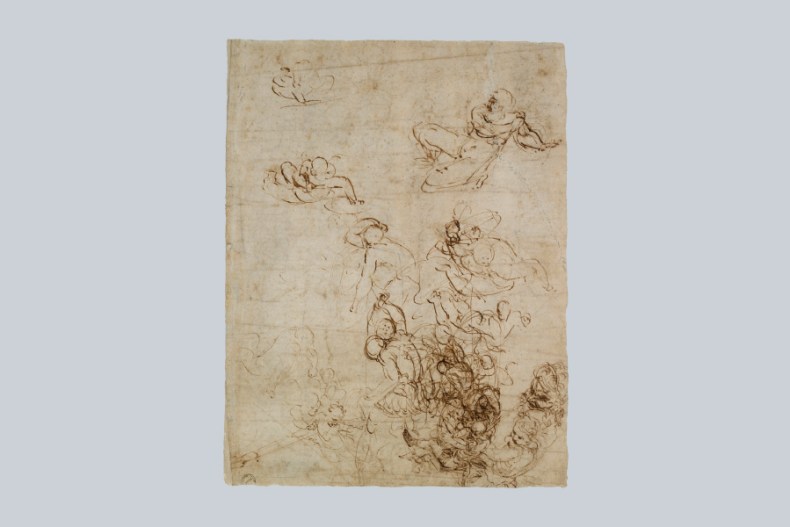

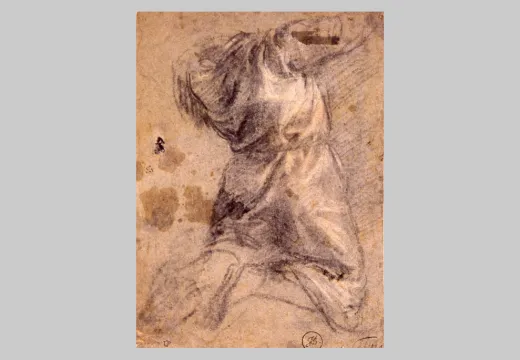

An exciting sequence of studies that encapsulates Raphael’s inventive fury has survived because of an accomplished drawing on the same sheet. At the upper left, in the most minimal of studies, a few hooked strokes conjure a complex form. At the bottom right, in the passage of wilder drawing, even as Raphael’s hand moved with different rhythms and pressures to discover forms in an inky vortex, he was recalling and adapting motifs from an earlier, more controlled study in red chalk over stylus showing fighting men. Here, excavations from memory and the familiarity of the hand with figural inventions are fused with furious improvisation. By contrast, on the other side of the sheet, Raphael used drawing as a mode of observation and representation in the meticulously analysed and constructed male nude study, probably drawn with charcoal.

Sheet with inventive ideas (c. 1511–14), Raphael. Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

A seated male nude (c. 1511–14), Raphael. Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

As well as convincing curators in a variety of institutions of the value of this exhibition, so that our many loan requests for precious Raphael drawings would be considered favourably, it was crucial to study the sheets afresh, scrutinising them for their inventive and gestural qualities and for the processes of drawing that they reveal. In an arresting sheet, extensive, almost invisible sketching with the blind stylus (a tool that indents the paper without leaving other traces) allowed Raphael to improvise freely before giving body to a stylish image in ink.

Hercules is modelled with directional hatching, his body invoking classical models while the arc of his drapery, its folds breaking into wave-like forms, signals physical effort and the thrill of victory. Raphael charged his pen with ink to add dark touch-points, enhancing the dynamic effects and creating graphic relationships across the sheet, so that the lion’s jaw chimes with the circling mantle. The pen drawing is deliberately free in parts, leaving the viewer to complete the monstrous form of the Nemean lion and conveying a sense of graceful nonchalance or sprezzatura.

Hercules overpowering the Nemean lion (c. 1507–08),

Raphael. Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

Looking closely at Raphael drawings is always a moving experience; considering the drawings in terms of their cognitive and affective aspects, rather than as stepping-stones towards the final painting, has been highly rewarding. A great advantage that I have as a university museum curator is being part of a wider academic community where connections across disciplines can easily be sparked. It’s been particularly stimulating to gather together specialists from subjects such as art history, Renaissance literature, medieval studies, musicology, theology or social anthropology in front of a selection of Raphael drawings in the Ashmolean’s print room.

Our open-ended discussions were immensely enriching, and the contributions of Stephen Farthing and Humphrey Ocean, both practising artists, were revelatory – from comments on the practice of drawing as a means of representing thought, to observations on the control of pressure in drawing, whether in chalk or ink, which is akin to changes in volume in singing or speaking. Other themes included the relationship of drawing with rhetoric, language and communication, and the nature of drawing as an unfolding, even conversational process that generates ideas. As I hope visitors to the exhibition will realise, drawings can do things that paintings cannot.

‘Raphael: The Drawings’ is at the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, from 1 June–3 September.

From the May issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home