During the Italian Renaissance, Florentine artists were at least as passionately devoted as any of their peers to the practice of drawing. More generally, however, the survival rates of drawings by individual painters of the period are notoriously variable, and are necessarily a consequence not only of how much they actually drew, but also of the subsequent fate of their works on paper.

Study for the face of a young woman (in the Madonna della Misericordia) (c. 1515), Fra Bartolommeo. Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam

In the case of the Dominican friar, Fra Bartolommeo (1473–1517), whose only rival among the home-grown painters active in Florence in the first two decades of the 16th century was Andrea del Sarto, around a thousand drawings – counting rectos and versos separately – make up his extant graphic corpus. Their numbers approximately correspond with the 883 sheets recorded in a post-mortem inventory that were then handed down to his pupil Fra Paolino, which suggests that his drawn oeuvre has survived almost miraculously intact. This body of work then seems to have remained in Dominican hands until 1725, at which point about half of it entered the Gaburri collection in Florence and was put into two albums, before finally being donated to the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen in Rotterdam in 1940. Had this material – which forms the core of the present offering, but has been supplemented by a select few judicious loans – fallen victim to fire, flood, or any other natural disaster over the intervening centuries, we would have considerably fewer Fra Bartolommeo drawings but it is not so obvious that we would be significantly less well informed about his draughtsmanship.

Study for a flying child angel (in the Madonna del Santuario) (1509), Fra Bartolommeo. Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen,Rotterdam

The main reason why this is so will be readily apparent to anyone fortunate enough to visit ‘Fra Bartolommeo: The Divine Renaissance’. Fra Bartolommeo is a supremely able and, at his best, ravishingly beautiful draughtsman, but even his warmest admirers could not claim he is limitlessly various. One reason for this, for which he can hardly be blamed, is that he appears to have emerged fully armed from the head of Zeus – so to speak – with the result that there is no juvenilia and only the most minimal sense of stylistic evolution over time. In terms of media, he favours black chalk, often in conjunction with white heightening on greyish or brownish prepared paper, and very occasionally complements this technique with deeply tonal brush drawings in distemper on linen. His employment of pen and ink is abnormally limited for the period, and tends to be reserved for the very earliest stages in the planning of compositions, occasional figure studies, and landscapes. He first employs red chalk late, after 1510, but it yields some of his most succulent productions. Arguably his most entrancing drawings are his studies of nature, which comprise both what might be described as slice-of-life landscapes and also detailed observations of single trees executed in spare pen and ink, but a mere three are on offer here. The other category of sheets that runs them close are his perhaps unexpectedly personalised head studies, which invariably seem to be drawn from life, and which include distinctly pioneering examples that combine red chalk for the flesh and black for the hair and/or draperies, of which three are on show.

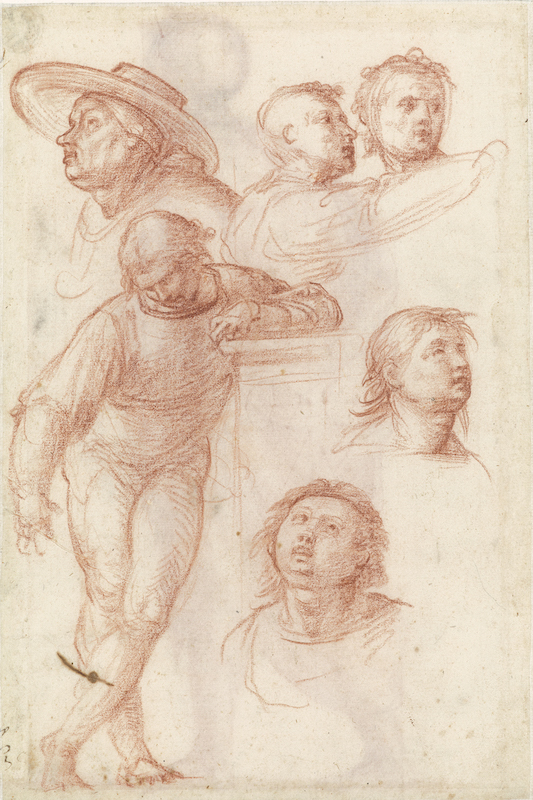

Young man leaning on a pedestal, and five heads (studies for bystanders in the Madonna della Misericordia) (c. 1515), Fra Bartolommeo. Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam

One of the main pleasures of studying Renaissance drawings habitually derives from the fascination of seeing artists only gradually reaching their destination in the finished work after all sorts of false starts. With Fra Bartolommeo, conversely, there are exceptionally few exploratory studies in spidery pen or sketchy chalk, and instead the vast majority of his known sheets show him refining an already carefully worked out visual idea, and exploring subtle variations on a theme; a number of the pleasingly hesitant first ideas for his Salvator Mundi, now in the Pitti, are a notable exception to this rule. At times, indeed, it is hard to grasp quite why he felt compelled to produce two or three only minimally differentiated studies of the same figure.

During the years 1990–93, an exhibition of a substantial number of the Boijmans drawings was shown in Rotterdam before moving on to no fewer than three venues in America; the present offering is in a sense a reprise of that venture, but will not travel. Not having been to any of those exhibitions, whether at home or abroad, I am unable to compare their displays with the present admirably relaxed and spacious arrangement, where studies for particular projects are grouped together and accompanied by aide-mémoire images of the end products in undistracting monochrome immediately above them, but there is one uncomplicated plus here.

Madonna del Santuario (Virgin and Child between Saints Stephen and John the Baptist) (1509), Fra Bartolommeo. Duomo di San Martino, Lucca

This is the presence of an inevitably select, but at the same time impressive, number of paintings by the master with which the relevant preparatory drawings can therefore be directly compared. Predictably enough, some of these are small-scale gems, such as the wings of the Del Pugliese tabernacle from the Uffizi, which are all of 18.3cm high, but there are also two monumental figures of prophets from the Accademia in Florence, and better yet no fewer than three altarpieces, all from the Museo Nazionale di Villa Guinigi at Lucca, which happen to be among his greatest achievements. In the case of both the God the Father with Saints Mary Magdalen and Catherine of Siena and the Madonna della Misericordia, it is their permanent home, while the Virgin and Child between Saints Stephen and John the Baptist is a temporary resident during the restoration of the chapel it normally inhabits in the cathedral there. Ironically, given that this is first and foremost a drawings show, they serve as a powerful reminder, were one needed, of quite what an impressive painter Fra Bartolommeo could be, and above all of the richness and radiance of his colours.

The exemplary catalogue of the present exhibition is the work of Albert J. Elen of the Boijmans and Fra Bartolommeo scholar Chris Fischer. Its bibliography lists no fewer than 24 publications – including the catalogue of the 1990–93 exhibition referred to above and other shows at the Uffizi and the Louvre – by Dr Fischer, and begs an obvious question. Would he be so kind as to put all of us Fra B. lovers out of our misery and publish a complete catalogue raisonné of the great man’s drawings?

‘Fra Bartolommeo: The Divine Renaissance’ is at the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam until 15 January 2017.

From the January issue of Apollo: preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home