In her video performance work Memory [Being Pregnant II] (1979/1980), Annegret Soltau smacks viewers in the face with the physical reality of the female body when it is with child. Cutting a forlorn figure as she stands in a room that is almost blindingly white, Soltau slowly rubs paint all over herself, giving prominence to the stretch marks that run across her swollen belly. She offers us close-up shots of her breasts and curls up into what seems like an uncomfortable position. Someone else, invisible in the background, begins to pull black thread over her body, encasing her in a fragile cocoon.

There is nothing in this sequence that bears even a weak resemblance to the images of happy, glowing pregnant mothers that are fed to women around the world. Soltau’s tale of her own pregnancy is terrifying, and yet it is also emboldening. Plucked free from the sexualised male gaze, the female body is free to present itself as it pleases, reclaiming the grotesque and transforming it into a political act.

‘The fear that my role as a mother could jeopardise my life as an artist inspired me to create a great many photos and videos,’ Soltau has said of her practice. The video may have been made almost 40 years ago, but the febrile anxiety that it conveys still possesses a sinister immediacy. One is firstly reminded of the total abortion ban in Poland that almost came into effect this year, thwarted only by the hundreds of women who took to the streets to oppose it. More recently, Ohio outlawed abortion after 20 weeks of pregnancy, in an ominous turn of events right after Trump’s shock win in the US elections. The hard truth that women’s bodies are still up for legal, political and artistic dissection and reconstruction (by men, obviously) is depressing.

Untitled (Lucy) (1975/2001), Cindy Sherman. © Cindy Sherman. Courtesy of Metro Pictures, New York / The SAMMLUNG VERBUND Collection, Vienna

Soltau’s video is just one of more than 150 works by 48 female artists currently on show at the Photographers’ Gallery. Women seizing the right to alternately build, document and destroy images of themselves: this is the theme around which much of the exhibition is curated. All of these seminal pieces are on loan from the Verbund Collection in Vienna, which has a specialist focus on conceptual and avant-garde art. Taking its cue from the zeitgeist of second-wave feminism, the show features the ‘usual suspects’ including Ana Mendieta, Cindy Sherman, Carolee Schneemann, Francesca Woodman and Martha Rosler, while shining the light on a legion of women whose work deserves more scrutiny.

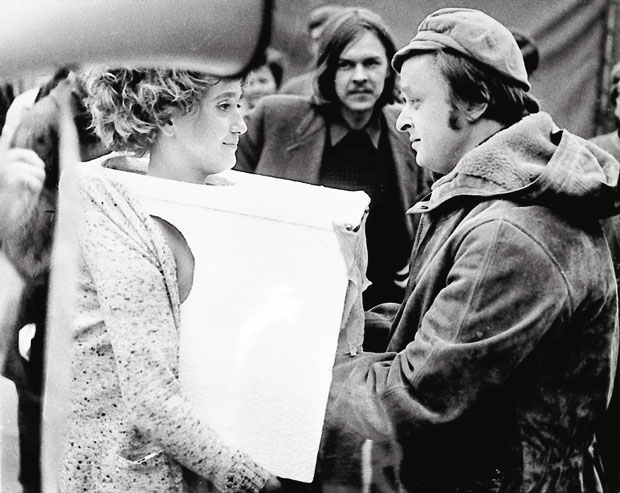

This juxtaposition of more established works against lesser-known ones is a curatorial strategy that succeeds brilliantly. Photographs of Suzanne Lacy and Leslie Labowitz’s public performance, In Mourning and Rage, are on display in the same space as VALIE EXPORT’s famous Tapp und Tastkino [Tap and Touch Cinema] (1968). Lacy and Labowitz, joined by participants from the Rape Alliance Hotline and other non-profit organisations, were protesting against the prurient coverage of the serial rapes and murders of multiple women in Los Angeles between 1977 and 1979. VALIE EXPORT (who took her artistic name from a popular brand of cigarettes) encouraged male passers-by to touch her bare breasts through a box on her chest while she stared them straight in the eye.

Tapp und Tastkino (1968), Valie Export. © Valie Export/ DACS, London, 2016. Courtesy of Galerie Charim, Vienna / The SAMMLUNG VERBUND Collection, Vienna

Two sets of photographs depicting how women regain control over the perception and portrayal of their bodies, two very different approaches and consequent meanings. In Mourning and Rage must be remembered as a perfect example of art-as-activism. The searing images of ten women, all dressed in black mourning hoods from the 19th century, were as powerful back then as they are today. The Rape Alliance hotline in LA pledged to start self-defence classes for women after the performance. It’s too easy to forget that art has the potential to change problems that exist outside of the gallery space: Lacy and Labowitz shake us firmly by the shoulders, telling us that rape culture is still rife today from Argentina to the UK, but creative expression can summon the public and political will to change things for the better.

Many of the works on display are underpinned by rage, but plenty more are plainly full of mischievous humour. In Renate Bertlmann’s short film Pregnant Bride in Wheelchair (1978), onlookers push the artist around in a wheelchair while an eerie lullaby plays on a music box hanging around her neck. She eventually ‘gives birth’ to a tape recorder encased in bandages and comically leaves the scene, clearly disinterested in being a mother to her ‘child’. Yet the feminist movement is not one that is impeccably streamlined, and even women themselves cannot be in unanimous agreement over what a feminist gesture ought to be. Bertlmann came under fire from other women for the copious use of sex toys in her work, and for making a hetero-normative departure from the female body as the starting point for feminist art. Elsewhere in the show, Martha Wilson’s Portfolio of Models (1974) takes a playful jibe at stereotypes of women and reveal them for the reductive caricatures that they are: the caption for the photograph of herself dressed as the ‘Working Girl’ reads ‘She works very hard, and is given no credit for any brains she may or may not have’. ‘These are models society holds out to me,’ she concludes. ‘At one time or another, I have tried them on all for size, and none has fit.’

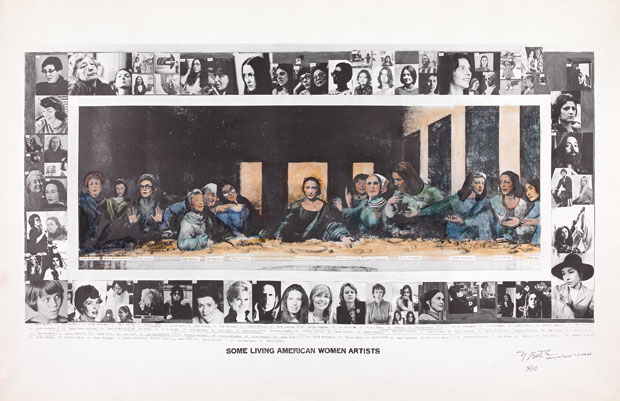

Some Living American Women Artists / Last Supper (1972), Mary Beth Edelson. © Mary Beth Edelson. Courtesy of Balice Hertling, LLC, New York / The SAMMLUNG VERBUND Collection, Vienna

Pregnancy, motherhood, unrealistic or simply perverse ideals of female beauty, unpaid housework, unequal pay, sexual violence, women navigating and negotiating the conventions of their relationship with men and society at large – these are issues that are unflinchingly explored in the show, which veers sharply between the corporeal and the conceptual as viewers move from one room to another. If the multiplicity of stories and voices presented here is anything to go by, it is clear that we have inherited the same (perhaps even worse) problems that these groundbreaking feminist artists were fighting to eradicate. The good news is that the capacity of art to satirise, challenge and mock misogyny in all its forms is continuously expanding. This show is both a salient reminder and an invitation to arms, and we musn’t squander the opportunity.

‘Feminist Avant-Garde of the 1970s: Works from the Verbund Collection’ is at The Photographers’ Gallery until 29 January 2017.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home