‘Trees are sanctuaries,’ wrote Hermann Hesse in Wandering. ‘Whoever knows how to speak to them, whoever knows how to listen to them, can learn the truth. They do not preach learning and precepts, they preach, undeterred by particulars, the ancient law of life.’

Under the shadow of climate change contemporary art is taking a leaf out of Hesse’s book, encouraging audiences to engage with trees, to listen to and learn from them – witness the Hayward Gallery’s devotion of its major spring exhibition to the theme ‘Among the Trees’. The many large-scale photographs, video projections and installations in this show require viewers to stand back to appreciate their impact, but – when I visited before the gallery’s closure due to the coronavirus – two paintings of the Amazon rainforest, Terraza Baja and Terraza Alta II (both 2018), were attracting closer attention, not only because of their relatively small size.

The artist responsible, Abel Rodríguez, saw the opening of his first European solo show at the BALTIC, Newcastle on 14 March (also currently closed due to Covid-19 precautions). I say ‘artist’, although Rodríguez would dispute the term. An elder of the Muinane community from near the headwaters of the Cahuinari River in the Colombian Amazon, Rodríguez – ethnic name Mogaje Guihu – regards his real work as the passing on of the indigenous plant lore he learned from his uncle, a traditional sabedor (‘man of knowledge’).

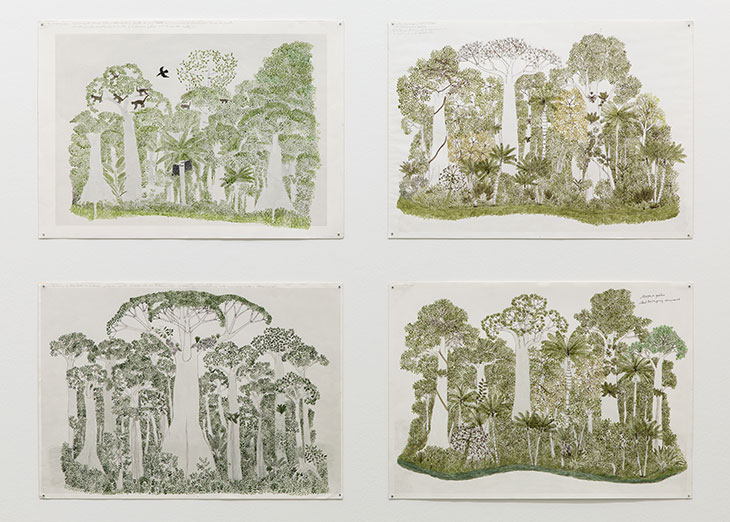

Installation view of ‘Abel Rodríguez’ at BALTIC Centre for Contemporary Art, Gateshead, 2020. Photo: Rob Harris; © 2020 BALTIC

In the 1980s he acted as a guide for teams of Western botanists researching the rainforest flora for the environmental NGO Tropenbos International Colombia; later, after being displaced by armed conflict to Bogota, he continued his work for Tropenbos by making illustrations of native plant species from memory. He had begun with felt-tip drawings on the Western botanical model illustrating the individual tree with its leaf and flower, but subsequently progressed to entire forest landscapes painted in coloured inks.

‘I had never drawn before,’ he says, ‘but I had a whole world in my mind asking me to picture the plants.’ One sequence of paintings shows the clearing of a patch of forest to build a longhouse or maloca; another details the creation of a communal allotment or chagra, with sympathetic planting of different native species, from yam and yucca to tobacco and coca. Conceived in exile, these descriptive drawings acquired a powerful imaginative life; on entering a gallery filled with them, you are transported.

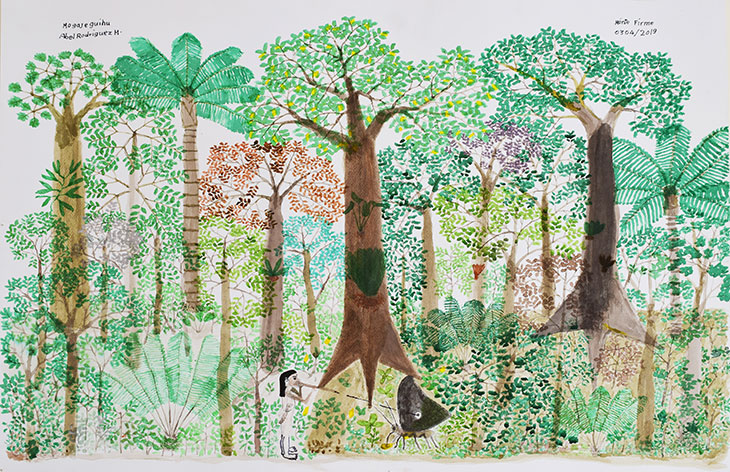

Monte Firme (2019), Abel Rodríguez. Courtesy the artist and Instituto de Visión

A knowledgeable insider of the world he depicts, Rodríguez is no ‘outsider artist’, nor could his self-taught paintings be called ‘naive’. His images are as intricate and skilfully drawn as the miniatures of medieval illuminators, which in their spiritual approach to nature they resemble. Their fluidity of design, harmonisation of colour and subtle treatment of light filtered through dense canopies of leaves is masterly. Thomas Struth says he wants audiences to get lost in the detail of the monumental chromogenic prints from his series New Pictures from Paradise (1998–2007), included in ‘Among the Trees’, and ‘surrender to just looking’. Rodríguez achieves the same effect on a modest scale with a brush and ink.

The closest Western equivalent to Rodríguez’s lyrical Ciclo Bosque de Vega (‘Cycle of the Flooded Forests’, 2009), with its vision of different species of trees, plants, animals, birds and fish living in Edenic harmony, might be the forest paintings of Roelandt Savery, the Flemish 17th-century painter to the imperial court in Prague who populated his paradisiacal treescapes with birds from the emperor’s aviary, including the dodo. Savery’s workshop painted Adam Naming the Animals (c. 1610), and Rodríguez is recognised as el nombrador de plantas – ‘namer of plants’ – but there the analogy ends. Savery’s pictures imagine a mythical Golden Age; Rodríguez’s paintings look back to a ‘golden age’ of such recent memory that he can summon it on paper.

Installation view of Ciclo Bosque de Vega (2009) in ‘Abel Rodríguez’ at BALTIC Centre for Contemporary Art, Gateshead, 2020. Photo: Rob Harris; © 2020 BALTIC

Since his inclusion three years ago in Documenta 14, Rodríguez has been in demand for contemporary exhibitions; his recent paintings commissioned for shows like the BALTIC’s have a different raison d’être from his original drawings made for Tropenbos with the aim of educating Western botanists in indigenous plantsmanship. In a documentary made after he won the Prince Claus Award in 2014 (and now available to view on the BALTIC’s website), the film-maker Fernando Arias asks Rodríguez what drawing means to him. ‘Well, nothing,’ he responds. ‘I simply draw images […] I draw things the way they are so they look beautiful.’ He distances himself from the Western view of art as a luxury with material value. ‘Others use different standards, while I do it for fun.’ As well as lessons in sustainable cultivation, this clear-sighted elder from the Amazon rainforest can teach us all a lesson in the value of art.

BALTIC Centre for Contemporary Art, Gateshead, is temporarily closed to the public due to the Covid-19 outbreak. For more information on ‘Abel Rodríguez’ (scheduled to run until 28 June) visit the institution’s website.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Has the Fitzwilliam lost the hang of things?