Archie Brennan began weaving at the age of 16 and didn’t stop for 70 years. The first major retrospective of his work, ‘Tapestry Goes Pop’, could not have found a better home than Edinburgh’s Dovecot Studios. Established in 1912 after recruiting weavers from William Morris’s workshops at Merton Abbey, the Dovecot was where Brennan served his seven-year apprenticeship and where, after further study at the Edinburgh College of Art, he returned as director from 1962 to 1978.

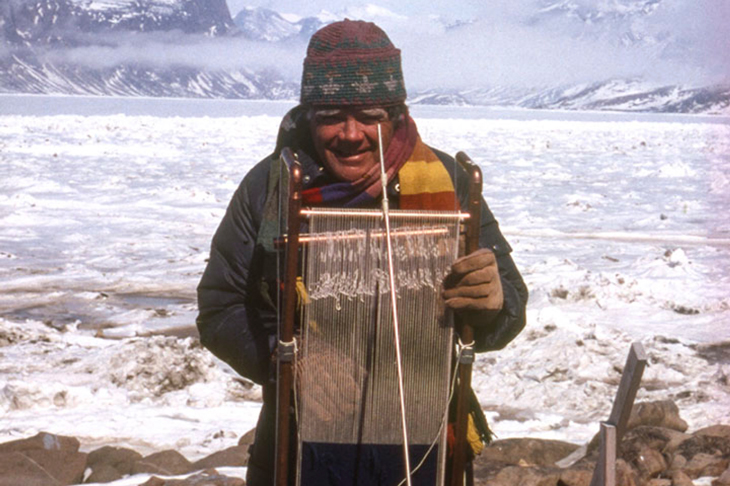

Born in Midlothian in 1931, to a large working-class family, Brennan described his parents, who were regular churchgoers, as ‘very socialist’ but ‘not actively so’. He said that his father, a manual labourer until retirement ‘probably – if he had been of a later generation – would have been involved in the arts’. At the Dovecot, Brennan was credited with instilling a sense of artistry among the weavers, who had previously seen themselves only as skilled copyists. In a documentary made in 1993 Brennan described the linear practice of starting from the bottom and working up without the opportunity to revise or redo what has gone before. ‘The real characteristic of tapestry weaving […] it’s almost like playing music. It’s more like living actually: yesterday’s played, done, finished – and then you get on with the next day.’

At a Window I, Spotted-Dress, Second Version (1980), Archie Brennan. Victoria and Albert Museum

The exhibition’s curators do not work from the bottom up. Instead they examine Brennan’s recurring subjects, such as window scenes and depictions of textiles, and his collaborative way of working. Though it is not always apparent when the tapestries are displayed in sequence in a single space, many were designed with specific surroundings in mind. Le Corbusier had argued that tapestries – which he regarded as ‘nomadic murals’ – should not create ‘windows’ that interrupt the wall with a vision of another place. Brennan clearly disagreed. In the At A Window series, he not only created views, but also trompe l’oeil windows to frame them.

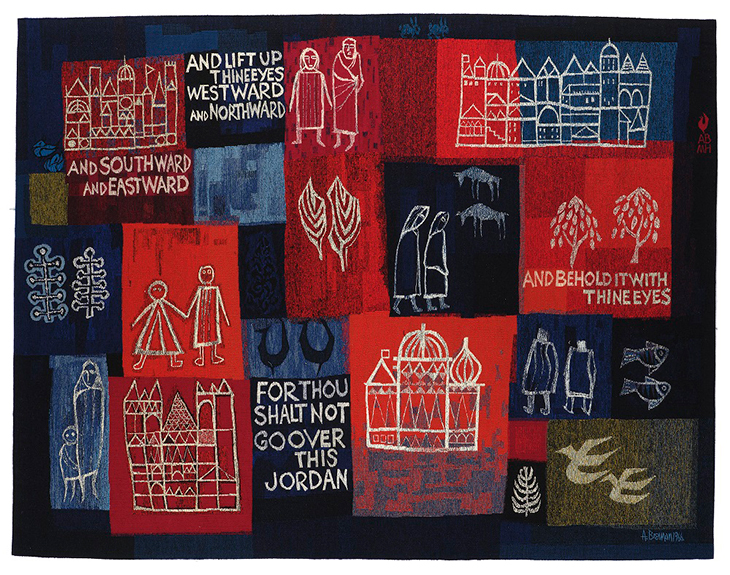

We can also see how public commissions shaped Brennan’s career, at a time when Scottish civil society was at its most daring, politically and aesthetically. In This Jordan (Refugees) (1966), on a shaded patchwork background Brennan intersperses ghostly, forlorn travellers with quotations from the Old Testament. The tapestry’s invitation to ‘behold it with thine eyes’ suggests we linger here, to consider both the stark contrasts between the red and navy patches and the gradations of colours within each. It refuses to shy away from the pain of borders and military conflict, but insists too on the potential of refugees to leave lasting marks and shadows on societies. The pair of doves in the final patch are flying against the current of the narrative, suggesting not only the hope of return, but the importance of standing up for justice in a climate of fear.

This Jordan (1966), designed by Archie Brennan and woven by Archie Brennan and Maureen Hodge. National Museums Scotland

Brennan combined his belief in craft with a distinctly international outlook. Overseeing the interior design of the parliament building of Papua New Guinea, he worked with weavers from the country’s National Art School, where he taught from 1976–1984. After moving to Hawaii in 1985, he felt aggrieved when his submissions were rejected by local galleries, but relished the opportunity of working relatively undisturbed at a time when his profile was rising in Scotland and mainland Europe. Brennan moved to the United States in 1993, the same year in which he wove Princess Kaiulani (Once upon a time), which depicts the half-Scottish heir apparent to the Hawaiian Kingdom that was overthrown by pro-US elements at the end of the 19th century. A ‘rip’ is woven across the face of the princess, pointing to this lost future and Kaiulani’s premature death.

Aberdeen (1964) is one of the most abstract works in the exhibition. Commissioned by the Aberdeen Art Gallery to reflect the city’s architecture and climate, it evokes the granite city not just through its subtle modulation of greys, but in its texture and very substance. The tapestry was woven in the year that the Continental Shelf Act came into force in the UK; its whirlwind of orange and black foreshadows the city’s rapid transformation in the oil boom decades that followed.

The Wine Cask (1974), Archie Brennan. Ardkinglas Collection. Photo: © Shannon-Tofts

In 1976 the critic Donald Kuspit argued that Pop art fails to challenge consumerism and simply reproduces it (it ‘gilds an already gilded lily seemingly making it sterling gold’). Brennan distinguished between ‘weaving illusions’ in his figurative work and his preoccupation with fabric subjects such as suits and ties. Tapestry becomes sculptural in works such as Old School Tie (1971) and Patch? (1992), which almost draw the subject matter out of the frame and into the gallery. ‘If you weave textiles in a tapestry medium, it’s half real already,’ Brennan explained.

As linear as weaving is, Brennan also took advantage of its materiality to reflect on his subjects; it is Brennan’s political consciousness – and self-consciousness – that distinguishes him from the pack. In the documentary of 1993, Brennan discusses his recreation of a newspaper column by Sue Arnold about crisps: ‘It just seemed to be a terrible bit of journalism from a very good writer.’ Two years later, he superimposed a panel of text bearing the words Was it worth it Mr Gutenberg? With this agit-prop intervention, he seems to be saying that reproduction, like patriotism, is not enough.

‘Archie Brennan: Tapestry Goes Pop!’ is at the Dovecot Studios, Edinburgh until 30 August 2021.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home