From the May 2023 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

‘To go to New York, you’re going to the centre of the world,’ the conductor Zubin Mehta once said. The international art market agrees. This month, the Independent art fair (11–14 May) kicks off a run of fairs in the city including the US edition of TEFAF (12–16 May), Frieze New York (17–21 May), the New Art Dealers’ Alliance fair (NADA; 18–21 May) and the 1–54 Contemporary African Art Fair (18–21 May). These coincide with major modern and contemporary art auctions at Sotheby’s, Christie’s and Phillips (16–19 May), which last year made more than $2bn.

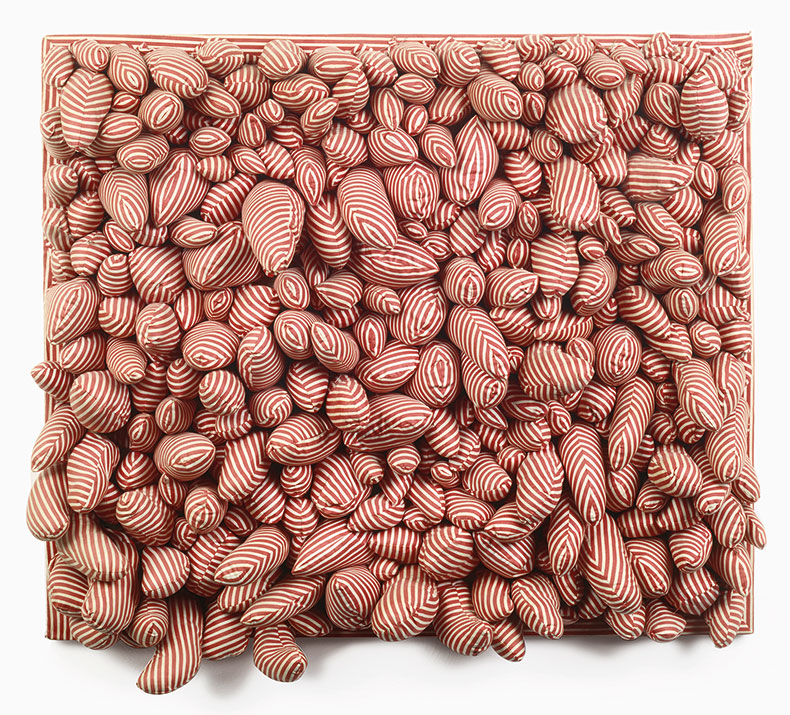

Red Stripes , 1965, Yayoi Kusama. Phillips, New York (estimate: $2.5m–$3.5m). Courtesy Phillips New York

New York surpassed Paris as the global centre of the art market in the years after the Second World War. Now it has been the biggest for so long that the fact barely attracts comment. The narrative over the past 20 years has instead been about globalisation and diversification. Markets have grown in the Middle East, Latin America and China. More recently, the revival of Paris has been the subject of much discussion. But while thousands of column inches have been devoted to that phenomenon, it now appears overstated. In fact, much of the art market is returning to its historical home.

‘We don’t tend to talk about New York so much, because New York is pretty much doing the same things we’ve always done, bringing high quality works to market’ says Robert Manley, deputy chairman of Phillips. Research published last month bears that out: while the global art market overall has barely increased, the US share of it, especially at the top end, has been quietly but noticeably growing.

In 2012, the total value of the worldwide art market was estimated at $56.7bn; last year this had risen to $67.8bn, an increase of 19 per cent over 10 years. Over the same period the value of the US art market alone – most of it in New York – has increased by 50 per cent: in 2012 sales were around $20bn, in 2022 more than $30bn. The United States now accounts for almost half the global market, rising from a 35 per cent share a decade ago.

‘The US has been the strongest performing market of the past 20 years,’ says Clare McAndrew, an economist and the author of the report, The Art Market 2023, published by Art Basel and UBS. ‘It benefits from a strong domestic market, with a big and broad base of wealthy collectors, but it is also a centre for international trade. So much of the art market is about perception. One of the drivers of its growth is New York’s increasing reputation as a place where big-ticket items will sell – it’s becoming a self-fulfilling prophecy.’ That might explain why imports of art into the United States for sale have risen by 74 per cent in the past two years.

At the preview of Sotheby’s Old Master auctions in London in December this trend was apparent. The star lot of the evening sale was a painting of Venus and Adonis, attributed to Titian and his workshop, which sold for £11.2m. But some felt it and the rest of the lots were overshadowed by a group of baroque paintings. These included Salome Presented with the Head of Saint John the Baptist (1609), by Rubens, which was destined to be sold in New York the following month, where it made just under $27m. ‘At both Sotheby’s and Christie’s, the most exciting pictures, what felt like the centre of Old Master gravity, were the pictures previewing for New York,’ the art historian Bendor Grosvenor said after the London auction.

It’s not just priceless Old Masters that are being hammered down in the United States. New York is the prime location for selling the most expensive fine art of all kinds. In 2022, New York accounted for 68 per cent of Sotheby’s, Phillips’ and Christie’s sales by value of all Old Masters, Impressionist, modern and contemporary art. That compares with just under 18 per cent in London, nine per cent in Hong Kong and almost five per cent in Paris. Forty-one of the top 50 most expensive works of art at auction, and all six that sold for more than $100m, were sold in New York.

US artists also dominate the auction market worldwide. Last year five of them – Andy Warhol, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Mark Rothko, Willem de Kooning and Cy Twombly – accounted for $1.1bn of the three main houses’ $5.7bn modern, post-war and contemporary sales. Works by US artists accounted for 55 per cent of all post-war and contemporary art sold at auction for more than $1m worldwide. Even young American artists, those born since 1977, are doing well. In 2022 they accounted for almost 40 per cent of sales by artists of their generation at auction.

Growth in the United States has also been driven by commercial galleries, although – as at auction – this is more apparent at the upper end of the market. The biggest growth reported to McAndrew came from the small number – around seven per cent of galleries worldwide – that have a turnover of more than $10m. These mostly have exhibition spaces in more than one location, typically London or Paris and New York.

Fifty-six years after the French dealer Daniel Templon opened his first gallery in Paris, he finally opened a space in Chelsea, New York, last October. He built his reputation by introducing the work of Americans such as Donald Judd, Ellsworth Kelly and Willem de Kooning to Europe. Templon has three other galleries, two in Paris and one in Brussels.

‘New York is the capital of the art world and we knew we had to be more present here,’ says Mathieu Templon, Daniel’s son and the US gallery’s director. ‘We felt we had to get closer to the American collectors and institutions, more than just doing fairs. And we had a number of artists without US representation.’ He will use the New York fairs in May to present a large exhibition of new work by the 87-year-old American artist Jim Dine.

Castle Farms (2022), Jim Dine. Courtesy the artist and TEMPLON, Paris – Brussels – New York; © Jim Dine Studio

Templon will soon be joined by another long-standing European gallery – White Cube – 30 years after it opened its first gallery in London’s St James’s. Now it has two large galleries in London and others in Paris, Hong Kong and West Palm Beach. Its New York gallery will be a remodelled former bank building on Madison Avenue. Susan May, White Cube’s director, says that discussions about opening in the city have been going on for at least a decade. ‘The US is a key area for us, for the market, for the artists and the cultural context. We do a lot of our business there,’ she says.

Even galleries without plans to open in the city say that New York is vital. Thaddaeus Ropac has galleries in London, Paris and Salzburg and opened a new gallery in Seoul in 2021. ‘America is the prime market,’ he says. ‘We may have put attention elsewhere for a while, but it has always been a priority.’ The gallery will be showing at both TEFAF and Frieze New York in May, at the latter creating a display centred on the late American painter, sculptor and performance artist Rosemarie Castoro.

‘New York is at least twice as strong as any region in the world at the moment,’ says Elizabeth Dee, co-founder of the Independent art fair. In 2016 she opened a second edition of the fair in Brussels, but it shut after three years. Now she runs a contemporary edition in May and a 20th-century version in September in New York. ‘Only here could you have fair after fair, week after week. In Brussels, if 20 families don’t show up, half your fair is finished,’ she says. ‘In New York, even if 1,000 collectors are out of town, there’s another 1,000 to show up and buy. We have the artists, the art schools, the collectors, the infrastructure, the regulatory and fiduciary frameworks. There’s nowhere else in the world that can say that.’

Nevertheless, most in the art market acknowledge that May’s fairs and auctions will be a test. The collapse of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank created jitters in March, as did the enforced buyout of Credit Suisse by UBS, Art Basel’s major sponsor. Last month Kristalina Georgieva, the managing director of the International Monetary Fund, said that with the war dragging on in Ukraine, the outlook for the international economy was worse than it had been for more than 30 years. The path back to growth over the next five years is ‘rough and foggy,’ she warned. There are already signs of the international art market softening. First-quarter auction results for 2023 globally were down by more than 13 per cent. But New York continued to buck the trend, with sales up 22 per cent.

Without doubt, the United States is best placed to weather any economic turbulence. London is wrestling with the practical implications and cultural bad karma of the Brexit decision. Art Basel Hong Kong was successful last month but millionaires and billionaires are deserting the city state, or at least moving their money, in the face of China’s authoritarianism. Paris is currently buoyant, but its growth could be stymied by proposed extra taxes on art and the complications of the soon-to-be implemented EU regulations on the import of cultural goods. Last month’s riots over pension reform are a reminder of the challenging level of bureaucracy that surrounds French employment law – a factor for all businesses in the territory.

New York, meanwhile, remains America’s most cosmopolitan and liberal city, as well as its richest, and instead of adding red tape to the art market, it has been stripping it away. The city has spent 75 years building a unique cultural infrastructure which appeals as much internationally as it does to Americans. As dreams of ever-increasing globalisation and diversification fade, troubles in the rest of the art world are once more New York’s gain.

Original data and analysis for this article was produced by the London-based research firm ArtTactic.

From the May 2023 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home