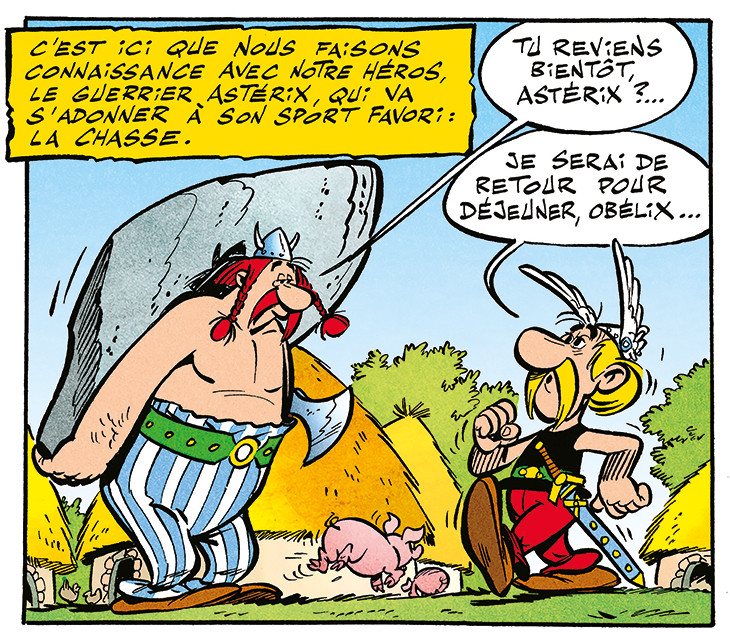

The roast boar is what comes to mind first. I had never seen a real boar, wild or tame, alive or dead, but René Goscinny and Albert Uderzo’s Asterix books made those forest-dwelling critters familiar indeed. Even though I had no idea how they tasted, I just knew that they would be delicious, utterly delicious. This conviction stemmed from Uderzo’s exquisite comic artwork. He depicted roast boar with an unctuous, dripping golden sheen, obviously juicy even on the dry page. When Asterix’s stalwart companion Obelix tucks in, he does so with his entire face, and the spittle flies – or is it sweat, or just emphatic enthusiasm? Whatever, the mouth waters in sympathy. Not since Anne Vallayer-Coster has an artist rendered cooked meat as so obviously, enticingly tasty. Scrontch!

Uderzo died on 24 March 2020, having produced Asterix comics for almost 60 years – 40 of those without Goscinny, who died in 1979. The duo had extraordinary combined gifts. Goscinny’s wit was almost superhuman, in particular his way with puns and literary allusions, but it was Uderzo’s art that made this fantastical series of stories – in which a handful of plucky Gaulish ‘barbarians’ hold out against the massed legions of Imperial Rome – utterly convincing. One might not believe that a single warrior could batter his way through a whole Roman legion, even when assisted by a magic potion, but seeing Obelix holding a legionnaire by the ankle and swinging him like a club to mow down his fellows, it all made sense. Paff! His figures were clownish, with big noses a speciality, but magically expressive, in particular when conveying haughtiness or frustrated annoyance, which they often did in surprisingly modern storylines about petty officialdom and Kafkaesque problems. And they inhabited a world of living, breathing detail executed with fabulous sureness down to every flagstone and drooping string of melted cheese.

Though the series happily played fast and loose with historical fact in favour of a good yarn – Asterix and Obelix encounter Vikings about seven centuries before there were Vikings to encounter – Uderzo took pains with the detail, accurately depicting Roman armour and dress and fretting over the anachronistic appearance of stirrups in an early edition of a story. And he had a way with surface effects that transcend the limitations of the ligne claire style and inexpensive comic printing: those succulent roast boars, the web of foam on the mountainous face of a stormy ocean.

With its over-arching theme of resistance and defiance, Asterix is naturally understood to be rooted in the trauma of the Second World War. But Goscinny and Uderzo’s Romans, for all their bellicosity, arrogance and delusions of innate superiority, are too personable to make a natural analogue for the Nazis. Instead, one could see in Asterix a more subtle critique of the France of the trente glorieuses after the war, prosperous and progressive but in danger of losing touch with a crude but vital part of its soul. The Romans in Asterix are not torturers and tyrants but bureaucrats and modernisers. Their empire is unappealing because it’s homogenised and a little boring, a world of traffic rules and service stations. ‘These Romans are crazy,’ the Gauls routinely comment, but often the joke is that they’re doing something recognisably 20th century – in other words the joke is on us, or on the world of the autoroute and the hypermarché. Asterix adventures are tales of revolt against unifying suburban staleness – for instance in The Great Feast, where Asterix and Obelix tour France collecting regional delicacies. Food is always at the fore.

Unable to prevail by violence, the Romans instead try to conquer the Gaulish enclave by subterfuge and guile. In The Mansions of the Gods, one of the best of the original run of stories, they attempt to gentrify the village into the empire by building a vast luxury housing development all around it and filling it with well-heeled Romans – where Mars failed, Minerva might triumph. This provides marvellous scope for satire, starting with a mendacious brochure on glossy marble, splendidly painted by Uderzo. Initially almost seduced by tourist denarii and urban sophistication, the Gauls fight back with magical acorns that re-grow the ancient trees as fast as the Romans can fell them, and ultimately the mansion block is depicted in ruins, entangled in roots like a jungle stupa, an image that completely captivated me as a child. Not the only time that Rome would face a devastating defeat in a forest.

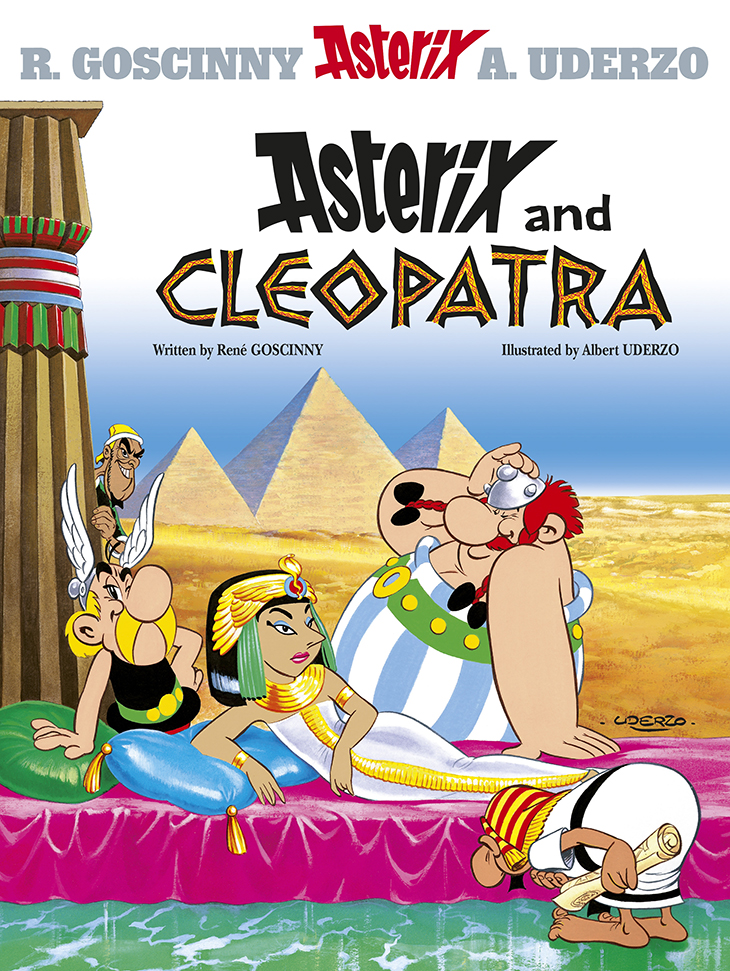

Asterix was not the same without the irreplaceable comic talents of Goscinny, but the art never wavered in the albums produced in more recent years. But perhaps a fitting memorial to Uderzo is the original cover to Asterix and Cleopatra, which lampoons the solemn braggadocio of the poster for the Burton/Taylor film. ‘The Greatest Story Ever Drawn,’ it proclaims, before listing the resources consumed by the production: ‘14 litres of Indian Ink, 30 brushes, 62 soft pencils, 1 hard pencil…’ (a solid illustrator in-joke there) ‘…27 erasers, 1984 sheets of paper, 16 typewriter ribbons, 2 typewriters, 366 pints of beer went into its creation!’ This manages, somehow to both be self-effacing and yet also to capture the intensity of effort, and the sheer love, that went into making these immortal comics.

Ave atque vale – all hail the genius of Albert Uderzo’s Asterix

René Goscinny and Albert Uderzo in the late 1970s. Photo: STAFF/AFP via Getty Images

Share

The roast boar is what comes to mind first. I had never seen a real boar, wild or tame, alive or dead, but René Goscinny and Albert Uderzo’s Asterix books made those forest-dwelling critters familiar indeed. Even though I had no idea how they tasted, I just knew that they would be delicious, utterly delicious. This conviction stemmed from Uderzo’s exquisite comic artwork. He depicted roast boar with an unctuous, dripping golden sheen, obviously juicy even on the dry page. When Asterix’s stalwart companion Obelix tucks in, he does so with his entire face, and the spittle flies – or is it sweat, or just emphatic enthusiasm? Whatever, the mouth waters in sympathy. Not since Anne Vallayer-Coster has an artist rendered cooked meat as so obviously, enticingly tasty. Scrontch!

Uderzo died on 24 March 2020, having produced Asterix comics for almost 60 years – 40 of those without Goscinny, who died in 1979. The duo had extraordinary combined gifts. Goscinny’s wit was almost superhuman, in particular his way with puns and literary allusions, but it was Uderzo’s art that made this fantastical series of stories – in which a handful of plucky Gaulish ‘barbarians’ hold out against the massed legions of Imperial Rome – utterly convincing. One might not believe that a single warrior could batter his way through a whole Roman legion, even when assisted by a magic potion, but seeing Obelix holding a legionnaire by the ankle and swinging him like a club to mow down his fellows, it all made sense. Paff! His figures were clownish, with big noses a speciality, but magically expressive, in particular when conveying haughtiness or frustrated annoyance, which they often did in surprisingly modern storylines about petty officialdom and Kafkaesque problems. And they inhabited a world of living, breathing detail executed with fabulous sureness down to every flagstone and drooping string of melted cheese.

Though the series happily played fast and loose with historical fact in favour of a good yarn – Asterix and Obelix encounter Vikings about seven centuries before there were Vikings to encounter – Uderzo took pains with the detail, accurately depicting Roman armour and dress and fretting over the anachronistic appearance of stirrups in an early edition of a story. And he had a way with surface effects that transcend the limitations of the ligne claire style and inexpensive comic printing: those succulent roast boars, the web of foam on the mountainous face of a stormy ocean.

With its over-arching theme of resistance and defiance, Asterix is naturally understood to be rooted in the trauma of the Second World War. But Goscinny and Uderzo’s Romans, for all their bellicosity, arrogance and delusions of innate superiority, are too personable to make a natural analogue for the Nazis. Instead, one could see in Asterix a more subtle critique of the France of the trente glorieuses after the war, prosperous and progressive but in danger of losing touch with a crude but vital part of its soul. The Romans in Asterix are not torturers and tyrants but bureaucrats and modernisers. Their empire is unappealing because it’s homogenised and a little boring, a world of traffic rules and service stations. ‘These Romans are crazy,’ the Gauls routinely comment, but often the joke is that they’re doing something recognisably 20th century – in other words the joke is on us, or on the world of the autoroute and the hypermarché. Asterix adventures are tales of revolt against unifying suburban staleness – for instance in The Great Feast, where Asterix and Obelix tour France collecting regional delicacies. Food is always at the fore.

Unable to prevail by violence, the Romans instead try to conquer the Gaulish enclave by subterfuge and guile. In The Mansions of the Gods, one of the best of the original run of stories, they attempt to gentrify the village into the empire by building a vast luxury housing development all around it and filling it with well-heeled Romans – where Mars failed, Minerva might triumph. This provides marvellous scope for satire, starting with a mendacious brochure on glossy marble, splendidly painted by Uderzo. Initially almost seduced by tourist denarii and urban sophistication, the Gauls fight back with magical acorns that re-grow the ancient trees as fast as the Romans can fell them, and ultimately the mansion block is depicted in ruins, entangled in roots like a jungle stupa, an image that completely captivated me as a child. Not the only time that Rome would face a devastating defeat in a forest.

Asterix was not the same without the irreplaceable comic talents of Goscinny, but the art never wavered in the albums produced in more recent years. But perhaps a fitting memorial to Uderzo is the original cover to Asterix and Cleopatra, which lampoons the solemn braggadocio of the poster for the Burton/Taylor film. ‘The Greatest Story Ever Drawn,’ it proclaims, before listing the resources consumed by the production: ‘14 litres of Indian Ink, 30 brushes, 62 soft pencils, 1 hard pencil…’ (a solid illustrator in-joke there) ‘…27 erasers, 1984 sheets of paper, 16 typewriter ribbons, 2 typewriters, 366 pints of beer went into its creation!’ This manages, somehow to both be self-effacing and yet also to capture the intensity of effort, and the sheer love, that went into making these immortal comics.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

Share

Recommended for you

Au revoir, Albert Uderzo – on Asterix in different tongues

Rakewell bids farewell to the co-creator of Asterix by taking a tour through his characters – and how their names have shifted in translation

George Herriman’s Krazy Kat – revisiting an abstruse but charming comic strip

The story of a simple-minded cat and his animal neighbours was never widely popular – but it counted E.E. Cummings and De Kooning among its fans

The comic strip genius of Charles M. Schulz

The man who invented Snoopy and the Peanuts gang revolutionised cartoons – both aesthetically and emotionally