How do you solve a problem like Thérèse? There she sits, defiantly, sensuously, hands clasped behind head and elbows thrust out, the folds of her red skirt gathered about her hips to reveal coltish legs and the gusset of her white underpants. Her figure is taut, riveted, her limbs brimming with the energy of adolescence; her puckered expression is both dreamy and absent. In this murky room, with its red-striped wallpaper and crumpled sheet, she’s alone with a man, who watches her with his paint brush. At her feet, a cat licks from a shallow dish, a visual substitute for his desire.

In 2017, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York refused to remove Thérèse Dreaming (1938) from display despite an online petition of nearly 12,000 signatures protesting against the picture on the grounds that it ‘romanticizes the sexualization of a child’. The petition, led by an HR manager at a Manhattan financial firm, called for greater nuance in the Met’s presentation of the ‘overtly paedophilic work’, and for its contextualisation when presented to a post-#MeToo audience. In the debate that followed, in which historians and critics leapt to the painting’s defence, one question asserted itself: what do we do, now, with the art of pervy men?

Thérèse Dreaming (1938), Balthus. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. © Balthus

The Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza’s answer seems to be: very little indeed. In its current exhibition, which displays 47 paintings by Balthus (1908–2001) spanning his career, Thérèse is no 21st-century girl, but a leitmotif of the artist’s work. Intimate and ambiguous, she’s a shorthand for Balthus’s style and for his exploration of in-between states, of childhood and adolescence, innocence and impropriety, realism and folklore. There are no warnings or apologies; instead, viewers are encouraged to consider the portrait in light of other legacies, of Balthus’s exile in post-war Europe, and of his continued identification with the Old Masters and the Renaissance. Any queasiness in his work – in his handling of female desire, and in his depictions of sexual violence – are symptoms of the otherness he claimed and of his professed desire to provoke.

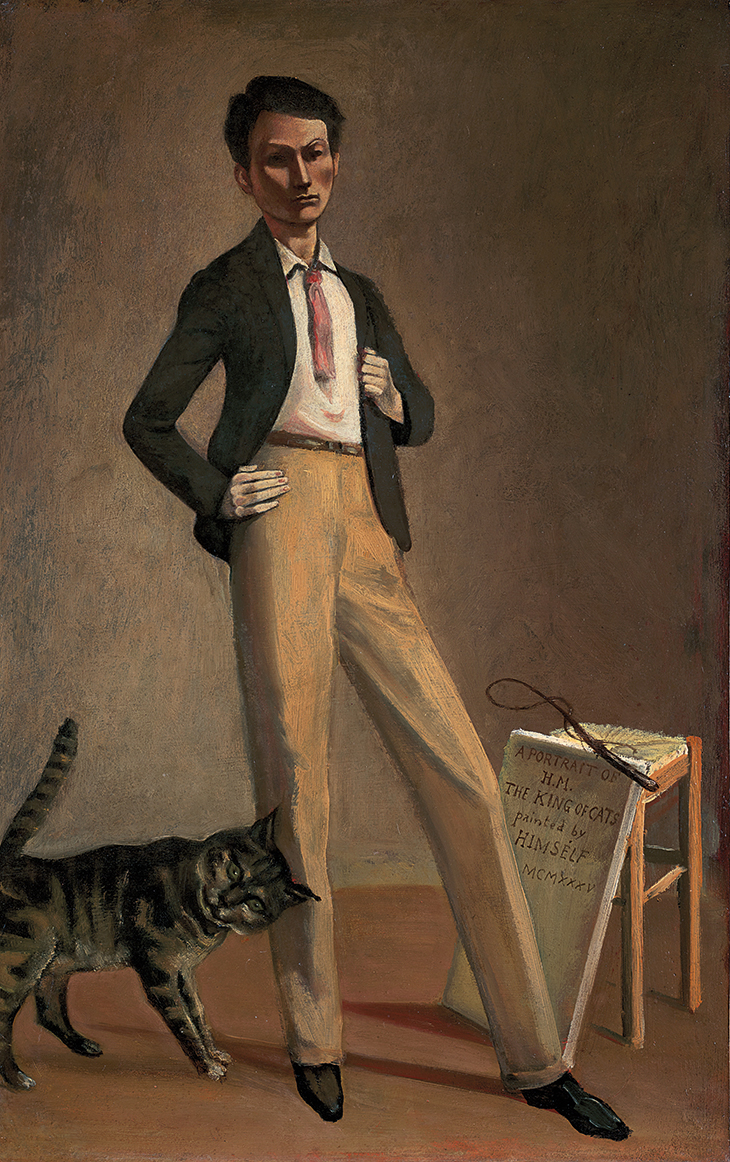

In Paris in the 1930s, after returning from military service in Morocco, Balthus (born Balthasar Klossowski de Rola) gave up painting small-scale sober landscapes in favour of society portraits. They were unflattering and a little malicious, in palettes of morbid browns, black, licks of red: Mrs. Paul Cooley (1937), drab as a secretary, perched on her spindly table; Woman with a Blue Belt (1937), sour-faced, in a brown serge dress with puff sleeves. His style was deliberately anti-modern, a blend of realism and folky mannerism: in The King of Cats (1935), he depicts himself as an intellectual dandy, gazing at the viewer with ironic self-assurance, his trousers creased along impossibly long legs. A muscular tomcat, his feline familiar, bristles against him.

The King of Cats (1935), Balthus. Musée cantonal des Beaux-Arts de Lausanne. © Balthus

During this period, Balthus was beginning to paint on a larger scale, rehearsing his odd, staged scenes. In The Street (1933), figures are arranged stiffly, children have too-old Renaissance faces, their gestures are frozen, the colours flat. He begins to develop his use of the colour red, which appears with varying degrees of subtlety throughout his paintings. Here it’s a cardinal red that loops across the canvas from left to right, accentuating jacket, dropped ball, popish cap and shoes. In the attempted embrace of the figures on the left, it’s easy to sense the threat of the 1930s, the girl’s wrist encircled, skirt clutched by her impassive captor. The redness brings out the painting’s artificiality but also its ambiguous symbolism, its religiosity and violence.

The Street (1933), Balthus. Museum of Modern Art, New York. © Balthus

The strangest paintings are the most interesting. Like Lewis Carroll and Heinrich Hoffmann, the author of Der Struwwelpeter, who inspired his own illustrations, Balthus teases and disturbs, giving us uncertain narratives and dream-like scenes. His austere interiors are peopled with surreal and recurrent motifs: card players, impish women, shining apples, candlesticks, knives sticking into loaves of bread. Two figures are at play in The Card Game (1948–50); the raised and squared shoulder of the male figure, leaning towards his opponent, and the banner-like colours of his costume, render him as a playing card himself. It could be a scene from Alice in Wonderland. The gallery’s two-year restoration of the painting, during which infrared was used to determine previous layers, has revealed the drastic simplification of the work; it originally depicted two female figures in detailed clothing, but the artist reduced clothing and upholstery to simple zones of colour. The Room (1947–48) is similarly plain. Its half-robed, central figure looks out at the viewer, arm raised in beatific gesture and bright palm open. In comparison to the earlier works, Balthus has softened his palette. Though still bathed in earthy shadows, the space is warmed by dusky colours: the rose-pink skirt of the crouching girl, the egg-blue mottling of the enamel ewer, the figure’s olive slippers, her tomato-red socks. As with all his interiors, Balthus resists cluttering; rooms are spared of bric-a-brac, with only one or two objects placed on mantles or sills. Once more, the use of red is suggestive; here, the girl’s socks, paired with her supplicatory gesture, recall Piero della Francesca.

In the final decades of his art, Balthus’s colours continue to soften, as does his depiction of female desire. In two final groupings – the first set of paintings completed at Chassy, a chateau in the Morvan where he lived in 1953, and the second in Rome, where he relocated in the early 1960s – female figures doze, languidly spread on sofas, the creaminess of their skin matching the paleness of the light. These works differ most from their predecessors in their handling of surface texture, in which matt pigments are overworked to create a scumbled, pearly sheen. The equivocal sexuality of the work has faded, and what we’re left with is lacklustre, a little dull. Thérèse, for all the discomfort her innocence and suggestiveness provokes, was Balthus’s bravest subject, and at her we should continue to direct our gaze.

‘Balthus’ is at the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid, until 26 May.

From the April 2019 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home