‘It is the little Jesus and his English nurse.’ That was Edgar Degas’s comment on Mary Cassatt’s Mother and Child (1899), with its oval mirror forming a halo behind the child’s head – a painting he teasingly hailed as ‘the greatest picture of the nineteenth century’. Degas’s response reflects the difficulty later viewers would have in classifying Cassatt. Was she traditional or forward-looking? A bourgeois or modern woman? American or French? Such debates will be reignited by ‘Mary Cassatt: An American Impressionist in Paris’ at the Musée Jacquemart-André.

The Philadelphia-born painter is more famous in the country she first left in 1865, aged 21, than in her adoptive France, where she died more than 60 years later. This exhibition of more than 50 oils, pastels and prints is, surprisingly, the first exhibition of Cassatt’s work in Paris since her death in 1926.

Mother and Child (The Oval Mirror), (1899), Mary Cassatt. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / image of the MMA

The daughter of an investment banker from Pittsburgh, Cassatt displayed a sense of strongmindedness early in her career. After an academic training at Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, she left for Paris where, unable to enrol at the École des Beaux-Arts (which only admitted men), she took private lessons from Jean-Léon Gérôme and Thomas Couture. Early success at the Salon with The Mandolin Player (1868) was followed by further acceptances, and she might have carried on in a realist vein but for two career-changing events: her rejection by the Salon of 1877 and her discovery of Degas, which she acknowledged as ‘the turning point of my artistic life’.

The respect was mutual. Having noticed her work in the Salon in 1874, Degas invited Cassatt to show with the Impressionists, which she did for the first time in 1879. Her compatriots were shocked. ‘She is a Philadelphian, and has had her place in the Salon,’ spluttered the reviewer for the New York Times. ‘Why has she thus gone astray?’ For the artist, the reaction must have been predictable after the rejection of her submission to the American section of the Exposition Universelle the previous year. She entered the same picture, on the rebound, into the Fourth Impressionist Exhibition.

Little Girl in a Blue Armchair (1878) is the sort of painting that, in its assuredness, definitively announces an artist’s arrival. In a large chintz-covered armchair a little girl in a white dress and dark tartan sash, exhausted from play, sprawls with her legs apart – a pose that would now cause an outcry if it had been painted by Balthus – with a lapdog curled up on the chair beside her. The picture has all the ingredients of Cassatt’s mature Impressionist style: the loose brushwork, the surprising colour combination of turquoise armchairs beached on a sand-coloured carpet, and the focus on the child as an independent presence in an adult world. In further Impressionist exhibitions, alongside her usual subjects of women sitting in gardens or taking tea, she began to include the paintings of mothers and babies that would form her reputation as a painter of ‘Saintes Familles modernes’.

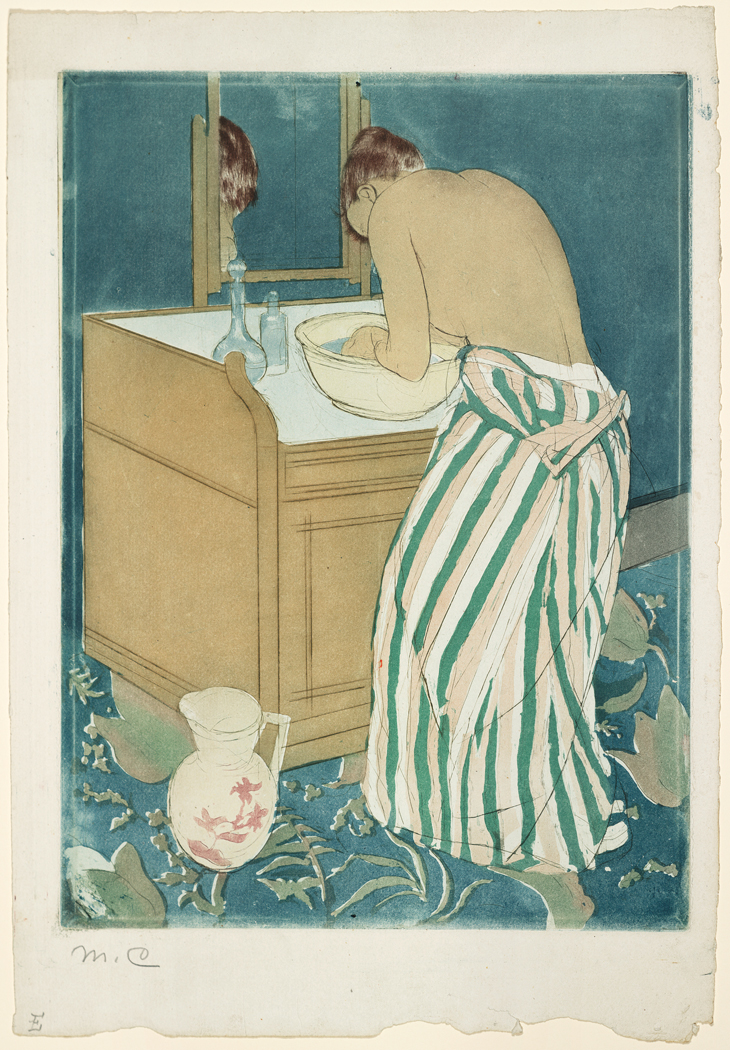

Woman Bathing, (1890-91), Mary Cassatt. Private collection

In 1871 Cassatt had travelled to Parma to copy Correggio’s Madonna of St Jerome for St Paul Cathedral in Pittsburgh, and, returning to Paris via Madrid, fell under the spell of Rubens’ flesh tones in the Prado. In her treatment of the theme of mother and child, she clothed Renaissance compositions in palpable flesh. She was not drawing on personal experience – she was childless – and the appeal of the subject was analytical rather than emotional. As in Renaissance paintings of the Madonna, the child is depicted as active, engaging with the outside world while the mother looks inward. In the pastel drawing The Stocking (c. 1889–90), the child reaches impatiently towards an object outside the picture frame while his impassive mother puts on his socks. It was the freshness of the child’s perception of a new world that attracted Cassatt as an artist.

The Stocking was an image she repeated in print, a medium that increasingly absorbed her from the 1880s. Her first major series of intaglio prints, including The Stocking, was acquired by the French state in 1890. But it was in colour printing that she found her own idiom. Her inspiration was the exhibition of Japanese prints at the École des Beaux-Arts in 1890, which she attended with the critic Philippe Burty. Challenged by his declaration that ‘No European could do that’, she determined to try, using drypoint and aquatint rather than woodblock and inking her own plates. The subjects were French, but the mood was Japanese: in In the Omnibus (1890–91), the Floating World becomes Edo-upon-Seine; in Maternal Caress (1890–91), the erotic encounter of a Shunga print is replaced by a mother’s embrace of a naked child.

Young Women Picking Fruit (1892), Mary Cassatt. Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh Photo © Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, 2017

As in her paintings, Cassatt’s colour choices in these prints are distinctive – but it is the flow of her etched line that is most seductive. Among the backhanded compliments from Degas that she was fond of quoting was his mock-incredulous response to her Woman Bathing (1890–91): ‘Did you draw this back?’ Working in colour, she could indulge her love of pattern in fabrics, wallpapers and carpets, presaging the interiors of Vuillard. She showed herself a Nabi in all but spirit – she was too pragmatic for that. While there’s a whiff of Symbolism about the strange painting Young Women Picking Fruit (1892), its strangeness doesn’t appear to symbolise anything. But compared with her friend Berthe Morisot’s pretty Cherry Pickers of the previous year, it can have served only to confirm one critic’s view of Cassatt as ‘the apostle of the ugly woman in art’.

Reviewing the Cassatt, Sargent and Whistler exhibition of 1954 at the Art Institute of Chicago and the Metropolitan Museum of Art – which has lent Mother and Child (The Oval Mirror) and The Cup of Tea (c. 1880–81) to this show – the art historian Edgar Richardson remarked on the ‘odd contrast between the boldness of her style and the world of perpetual afternoon tea it serves to record’. That contrast is just one of many contradictions this exhibition leaves tantalisingly unresolved. Perhaps we should just accept the verdict of the great Impressionist dealer Paul Durand-Ruel: ‘Miss Cassatt’s work is so great that she paints in a school she has created for herself.’

‘Mary Cassatt: An American Impressionist in Paris’ is at the Musée Jacquemart-André, Paris, until 23 July.

From the May issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home