Brian Clarke has packed more into his 50-year career than seems feasible. He has been commissioned to design stained glass for buildings by Norman Foster and Zaha Hadid, and created paintings, tapestries, mosaics, and more – alongside odd jobs such as designing stage sets and album covers for Paul McCartney. All this is a long way from his beginnings as a scholarship student at Oldham Municipal School of Arts and Crafts, Manchester. Here he learned calligraphy and bookbinding, among other subjects, before creating his first piece of stained glass at the age of 16. ‘I asked Francis Bacon once if he’d ever thought of designing stained glass, and he said: “No – and I’ve never done any macrame either, dear.”’ This is no chance name-drop. Since Bacon’s death, Clarke has been chairman of the painter’s estate. It’s in part this association with the raucous art scene of 1970s London – and the punk movement, via collaborations with Vivienne Westwood and Malcolm McLaren – that has led to Clarke being called ‘the rockstar of stained glass’.

Though far warmer in person than his demeanour in photographs might suggest, there are, it’s true, still some rockstar-like aspects to his behaviour (as we speak, he sips from a wine glass filled with Monster energy drink). Not least among these is a life-long habit of falling out with the directors of major museums. ‘I used to say it doesn’t matter because they’ll retire or die, then there’ll be a new generation of them, but now I’ve had rows with all the new ones too,’ he says with a laugh. ‘British museums have made a point of ignoring me my entire career.’ He is still furious that the Tate museums don’t exhibit more works by Bacon (‘along with Turner, probably the greatest painter we’ve ever produced’) and describes Tate Modern with scorn: ‘It’s like the pleasure beach at Blackpool – it’s all about footfall.’

Brian Clarke photographed by Mary McCartney

In this permafreeze of institutional apathy – or is it antipathy? – to his work, Clarke has seized an invitation from Damien Hirst to exhibit at his Newport Street Gallery in Vauxhall in south London. Though the show was originally conceived as a full-career retrospective, the exhibition’s curator Hans Ulrich Obrist has focused four of the six galleries on recent work and the remaining two are filled by pieces made in the last 20 years. Among the newest is The Stroud Ossuary (2023): a commission from Hirst, destined for his 16th-century house in Gloucestershire. Once installed, seven stained glass panels will snake up the building in tiers. These are filled with a total of 1300 human skulls, depicted in monochrome and framed with lead on vividly coloured grounds. Many of these skulls were sketched from life, based on both Hirst’s and Clarke’s collections of human remains, and from the ossuaries of Romney Marsh. The two artists have a shared taste for this particular motif – Clarke has been incorporating skulls into his work ever since the deaths of his mother and brother. Those earlier examples were rendered in the opaque blackness of lead, without glass: an inversion of the supporting role the metal has traditionally played in stained glass.

Detail from The Stroud Ossuary (2023), Brian Clarke. Courtesy Brian Clarke Studio

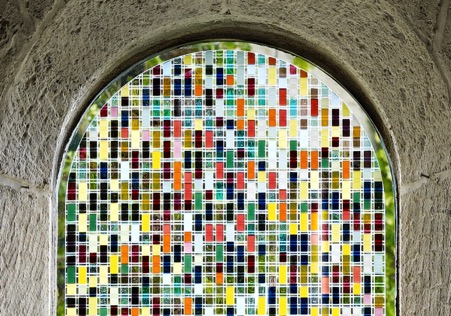

Though far smaller than his largest works, the biggest piece seen here is a mighty 42-metre-square wall of stained glass, mouth-blown by the many craftspeople working for the artist; he employs up to 100 at any one time. The title Ardath (2023) translates from Hebrew to ‘flowering field’. Abstracted blossoms appear as if splashed, liquid-like, across the monumental surface. Ardath was commissioned for a multi-faith centre, which points to a paradox in Clarke’s practice: after discovering stained glass as an 11-year-old visiting York Minster, he has spent a lifetime trying to forge a secular identity for the medium. He is scathing about the Church of England’s role as a patron over the last century – ‘almost, to the point of obsession, in pursuit of mediocrity’, as he puts it. ‘I don’t know if stained glass has a future of any significance. But if it does, then that future has got to be in the secular urban fabric,’ says Clarke. And yet, religious references crop up time and again. The title of the Newport Street Gallery exhibition, A Great Light, is taken from Isaiah 9:2 (‘The people who walked in darkness have seen a great light’) and in his recent watercolour series, Vespers. Perhaps the association of stained glass and spirituality is unavoidable. As Clarke says, ‘With the trans-illumination of colour dancing across the engineering, the stonework, the floors, the people – it’s not surprising that light is often used as an analogue for the divine.’

As we speak in his Arts and Crafts home, my eye is drawn back time and again to the works that surround us. Among many others, I spot a Le Corbusier maquette for stained glass, destined for the Unité d’Habitation in Marseille; a Max Ernst design casually propped on the floor; a glorious maquette for a rose window by Matisse. On this latter, he notes: ‘Matisse and Chagall both said at the end of their lives that had they discovered stained glass earlier in their careers they would have abandoned painting.’ Twentieth-century stained glass is a passion of Clarke’s, who became hooked after encountering avant-garde examples from post-war Germany – in particular, the art of Johannes Schreiter. Eventually, the artist realised he had built up an extremely substantial collection spanning eight centuries. Might the future hold a Brian Clarke Centre for Stained Glass to show these works publicly, I venture? ‘I think the answer to that is quite possibly, yeah.’

Flowers for Zaha (2016), Brian Clarke. Courtesy Brian Clarke Studio

The desire to share a lifetime’s knowledge has led to a new project: a memoir that combines autobiography with the history of stained glass over the last millennium. Ill health has slowed this project down – though while in hospital, Clarke still managed to produce more than 200 collages – but he remains ebullient, brimming with ideas and plans for the future. ‘People say, “Do you aspire to being as great as the medievals?” No, I want to surpass them – I want to go beyond Chartres [Cathedral]. And there is really the potential to do that,’ he adds. ‘I have never been as excited about the potential of the medium in my entire life as I am today.’

‘Brian Clarke: A Great Light’ is at Newport Street Gallery, London from 9 June until 24 September.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home